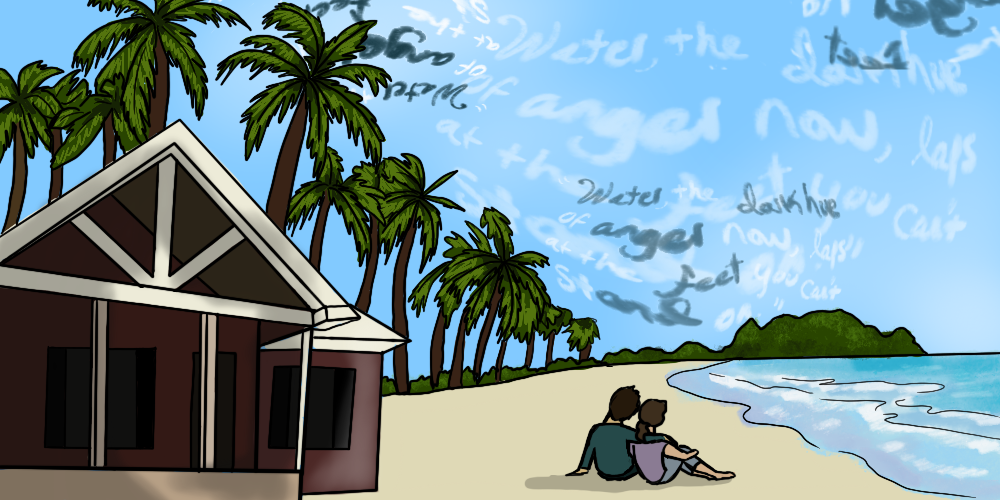

Months after I move from my apartment to this ranch house in upstate New York, I find my favorite frying pan boxed beneath a pile of winter boots, but where is my Pablo Neruda with the coffee stain on his odes? Where is my dog-eared Patricia Smith’s Blood Dazzler that brings me into the maelstrom of Hurricane Katrina? I can only recall one line — “Water, the dark hue of anger now, laps at the feet you can’t stand on,” but I can’t forget the portrait of despair Smith created in “Ethel’s Sestina.” I can’t forget Ethel Freeman, whose body sat in her wheelchair outside the New Orleans Convention center for days. I can’t forget her son, Herbert, forced to abandon her.

Where is Li-Young Lee’s The City in Which I Love You? It echoes The Song of Songs and makes me miss the city in which my husband of 55 years and I lived together before he was diagnosed with the worst type of dementia, Lewy body, and had to be moved to a nursing home. And now, this upstate New York ranch house I bought for us, larger than what we could ever afford in Manhattan, thinking that with an aide I could care for him at home, only hears my footsteps.

I cut the tape holding fast the doors of a small cabinet and find Staying Human, an anthology edited by Neil Astley that contains a poem by the Macedonian poet, Nikola Madzirov. The title alone, “When Someone Goes Away Everything That’s Been Done Comes Back,” speaks to my life. “I live between two truths / like a neon light trembling in / an empty hall.”

As I rinse a pint of blueberries, I am suddenly holding my husband’s hand at the MOMA, backing up, going forward, squinting to find the greenish or reddish or bluish squares within the seemingly all-black canvases of Ad Reinhardt. If I hear the soft coo of the mourning dove, my husband and I are at the Metropolitan Opera, silently weeping over Mimi’s death from tuberculosis as we now grieve the deaths of so many from Covid, especially the hard-hit poor like Mimi and Rodolfo. Spring, I am transported to the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, bending with my husband, I shaded by my parasol, him by his straw bowler, to read the inscriptions in the Shakespeare Garden. “There’s fennel for you, and columbines: there’s rue / for you; and here’s some for me.” — Hamlet.

I keep Tess Gallagher’s Moon Crossing Bridge on my night table. While taking a bath as hot as can be borne, Gallagher, in “Now that I am Never Alone,” recalls that once her husband, Raymond Carver, “. . . pulled my head against his thigh and dipped / a rivulet down my neck of coldest water from the spring / we were drinking from. . .”

Poetry allows me to experience my near widowhood and mercifully delivers me from brooding. I collect words that I haven’t seen recently, such as “snigger,” “lollapalooza,” and “maenad” (meaning madwoman.) That one I had to look up. I scribble margins with the ingenious liberties poets take, such as matronhead that Sharon Olds came up with in her latest collection, Odes. In her earlier work, Olds had shown me how it’s possible to admit all the abuse my father rained on me with his prizefighter fists, and yet lionize him. Now, aging along with me, Olds has a lot to say about a woman in her later life. In “Ode to the Hymen,” she imagines her mother as the big fortress around her, the matronhead around the sweetmeat of her maidenhead.” Matronhead is coined from two separate words — matron head, a copper penny minted in 1793 that bore an older woman’s face.

By looking at structure, poetry forces me out of myself. I always marvel at how Molly Peacock writes sonnets that are strong narratives since I, a narrative poet, am such a sonnet klutz, thumping da-dum, da-dum, yet never finding the right words to match. But Terrence Hayes’s book, American Sonnets For My Past and Future Assassin, which I found yesterday in the carton clearly marked BOOKS, shows me what feats a modern sonnet can perform. “I lock you in an American sonnet that is part prison, / Part panic closet, a little room in a house set aflame.”

Since I need to be near my husband who can no longer travel, I search for poets who bring me to other countries. Anne Casey, author of four critically acclaimed collections, an Irish poet who now lives in Australia, keens for her homeland. In “Past the Slip,” she writes, “No gulls today— / the stiff breeze phantoms their haunting / calls, warm and peppered with salt, a far cry / from where you and I once walked side by side.”

I was too keen for the sea that was only a block from my childhood home in Rockaway Beach, New York, the salt air rusting the chrome of our black Mercury and fuzzing my curly hair, the gulls crying like lost souls. I met my husband at the beach when I was 14, he 17, so I am a sucker for sea poems.

This one, “i am the sea,” is by Ali Whitelock, a Scottish poet who also emigrated to Australia, author of The Lactic Acid in the Calves of Your Despair.

“the sea heaves / swallows itself down / like cough syrup in thick slow gulps.”

She is there with her brother, Andrew, who flies a kite. I remember my husband flying one, facing me, laughing, running backward on the beach, all 6’4” of him. I thought he looked like a winged god.

I love poets, wherever they are from, who let me experience their culture. For example, Danusha Laméris, an American poet of Dutch and Caribbean descent, in “Insha’Allah,” meaning if God wills it, writes, “Every language must have a word for this. A word / our grandmothers uttered under their breath.”

Reading this, I can hear my Russian grandma, my bubbie, say, Halevai (if only it were so). “Halevai, I should live to be at your wedding one day.” “Halevai, may your cousins come home alive from the war in Korea.” “Halevai, may no bombs fall on us.”

In this, my first winter alone in our unfamiliar house, I cannot believe how the wind whips through the double-glazed windows.

My husband, are you warm at the Home? Do you remember how to ask for an extra blanket?

When I think of having to go on without you, I ask myself the question Mary Oliver poses in “The Summer Day.” “What will you do with your one wild and precious life?”

I will, like Galway Kinnell in “Oatmeal,” ask Keats to have his gluey porridge with me, and fill me in on how he wrote “Ode to a Nightingale.” I will lunch with Frank O’Hara’s “Lunch Poems,” then roam the streets of our beloved Manhattan together. I will invite Ben Jonson for dinner. His man will “read a piece of Virgil, Tacitus, / Livy, or of some better book to us, / of which we’ll speak our minds, amidst our meat.”

I will tuck poetry into my duvet at night, dream on it, and hope it dreams of me. Halevai. •