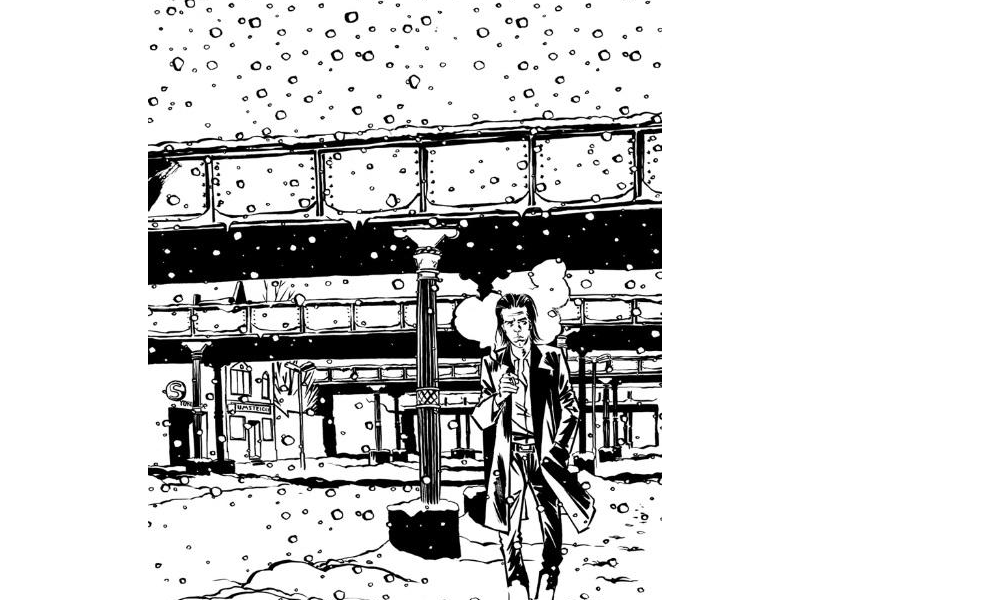

A feverish, drug-addled musician huddles on the floor of his room in Berlin, pecking out his first novel on a typewriter. He’s tormented by the protagonist he’s creating: a mute, misunderstood creature who expresses in violence what he’s unable to communicate in speech. At the same time, this Australian musician is inspired by the artful anarchy of the German bands around him. He abandons his own band, the influential post-punk group The Birthday Party. He seems intent on blowing up his life.

These are just a few of the scenes in Nick Cave: Mercy on Me, published September 19, 2017, in the U.S. A 300-page, black-and-white graphic novel about Nick Cave was never going to be a light read, but this is gripping stuff.

The book is being marketed as a graphic biography, but it isn’t exactly a biography. It’s flexible with personal details and timelines, so you won’t get a complete accounting of Cave’s career and life here. For instance, PJ Harvey, Cave’s one-time girlfriend and duetting partner on “Henry Lee,” gets only a single panel. This is much less than Kylie Minogue and her alter ego from “Where the Wild Roses Grow.”

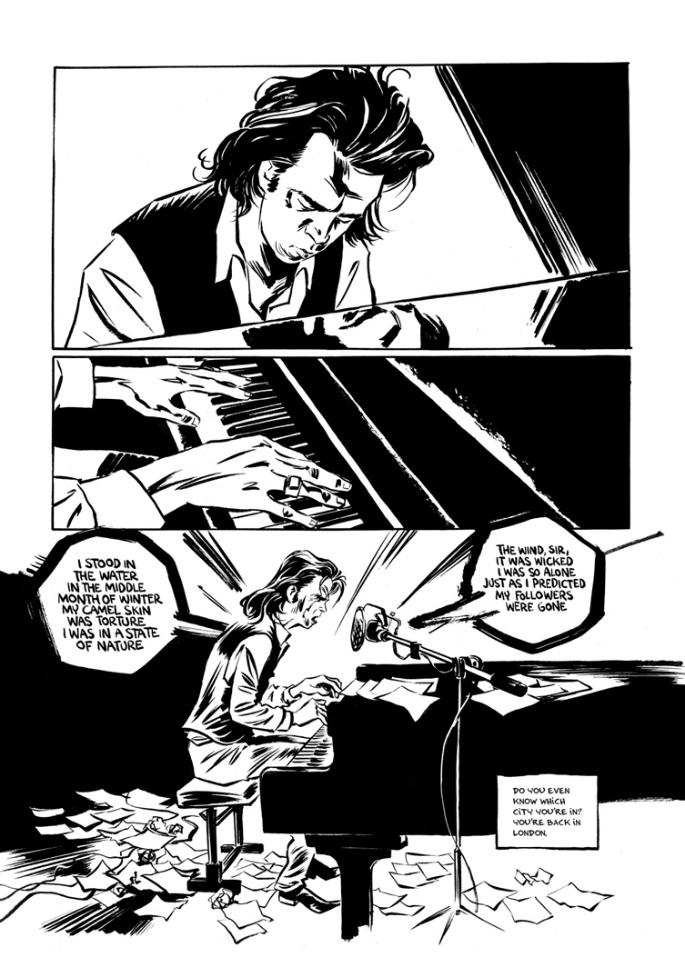

What matters more is capturing the mood of Nick Cave’s work. Lyrically, this output tends to be obsessed with death, religion, and deviance. Musically, the styles vary from dissonant post-punk to gospel-influenced rock and somber piano balladry. The book succeeds in reflecting this overall mood, with dark, expressive inking and a narrative that draws heavily on Cave songs and writings.

I talked with the author of Mercy on Me, Reinhard Kleist, about working with the head of the Bad Seeds and finding the right approach to telling his story.

First of all, Kleist was a fan. “Nick Cave is one of the biggest storytellers that we have in the music world,” Kleist says (although he admits to not being sold on 2003’s Nocturama). “What I’ve always liked about his music is that it has such strong images.” This is naturally good fodder for a cartoonist.

Kleist wanted to do another musician comic following the (also excellent) Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness, as he appreciated the challenge of “trying to make music visible in a comic book.” As well, he wanted to work on something lighter, following graphic biographies of Fidel Castro and Harry Haft, a Polish boxer who survived Auschwitz.

It’s oddly amusing that Kleist considers the Cash and Cave books fun and light. The former is about prisons, figurative and literal, while the latter explores the destructive aspects of the creative impulse. Both examine addiction and obsession with mortality. “I’m not a very light person, I guess,” says Kleist, deadpan.

It was important for the project that he build up a relationship with Cave. Happily, Cave was a fan of the Johnny Cash book. So Cave and Kleist worked together from the beginning of the project — this wasn’t a collaboration, exactly, but it did involve getting authorization from Cave for the direction and checking in with him periodically. Kleist comments, “I was really happy from the beginning of the project that he trusted me with his biography.”

Kleist is frank that Cave’s endorsement of this project means that it wasn’t independent of his influence. This was clear from the start, when Kleist had to find an entry point that wasn’t too literal. The Johnny Cash book was more of a traditional biography. It centered on Cash’s performances at Folsom Prison and gave plenty of space to a real-life inmate, Glen Sherley, who struck up a friendship with Cash that ultimately soured. Overall, it was generally faithful to the well-known details of Cash’s life.

Mercy on Me, which is about another black-suited, darkness-embracing musician noted for his storytelling, goes further in blurring the lines between reality and fiction. “Why not have some part of his story be told by his characters?” Kleist wondered. So plenty of characters from Cave’s songs and books have prominent roles here.

We follow the mentally exhausted man on death row about to be executed in “The Mercy Seat,” and we catch glimpses again and again of the doomed Elisa Day before her body is laid to rest “Where the Wild Roses Grow.” These are almost music videos in graphic form. While Cave’s life isn’t literalized, these songs are, to hallucinatory effect. For example, Cave meets long-dead bluesman Robert Johnson, who’s mentioned in “Higgs Boson Blues,” surrounded by flames.

And we watch as Euchrid, the protagonist of Cave’s novel And the Ass Saw the Angel, morphs into and talks with other people, including Cave himself. Kleist saw a lot of Cave in the novel. For one thing, Euchrid’s muteness paralleled Cave’s speechlessness during his ’80s period in Berlin, as he didn’t speak German. Euchrid also dwells in a literal swamp, an appropriate metaphor for Cave’s drug-fueled, claustrophobic existence in Berlin. “I think one of the only reasons he survived is because he could get the best drugs,” Kleist muses.

This treatment of Cave’s work and life wasn’t the original angle for Mercy on Me. Cave was politely dismissive of Kleist’s first ideas, which were more straightforward. Kleist says that one thing he realized in the back-and-forth was that Cave “has a very special way of looking at his own history.” This includes sometimes talking about himself in the third person. Cave creates a sort of distance between himself and his persona, and Kleist decided to tap into that by creating a book that was more mythology than biography.

Ultimately, Kleist says, Cave “became a character of mine in the end. Actually, I created my own Nick Cave.” This meant that research was less about excavating biographical details and more about threading out the theme of the immortality of art. In fact, “the more information I got, the more I got away from the real idea.”

A poignant example is the 2015 death of Cave’s 15-year-old son, Arthur. Kleist was horrified when he found out, midway through working on Mercy on Me: “I didn’t believe somebody would survive something like this.” But, to Cave’s relief, there was never a question of working this tragedy into the book, the way a conventional biopic might have done.

For one thing, it wouldn’t have worked structurally. In Mercy on Me, the present is never very prominent. In the space of a few pages, the book moves from 1994’s “Red Right Hand” to 2013’s “Higgs Boson Blues,” the last song to be visualized.

This epic song, with its infamous shout-out to Miley Cyrus, is a good place to close the book. It takes in existence and destruction at a cosmic level, after all. This is fitting for a book, and a musician, that’s obsessed in an almost theological way with the relationship between a creator and his creations.

Euchrid asks Cave at one point, “Is this what you seek? You wish to be able to capture the sound rioting in your head? Tame the cacophony and turn it into music?” This works as a good summation of Mercy on Me. •

All images courtesy of the author.