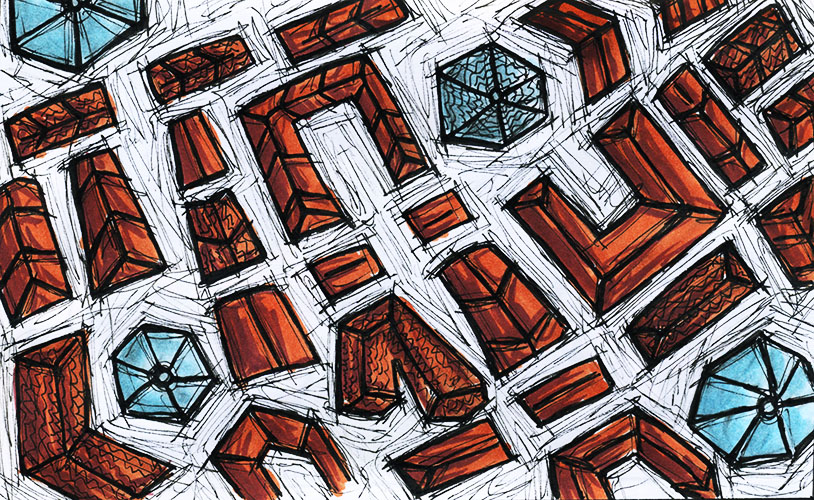

When seen from above, the city center of Prague resembles a spider’s web, links of lean medieval streets that branch forth from the old town square and issue out towards the Vltava river. Wherever you happen to find yourself along this section of the river’s bend, you will invariably see Letná Park, and rising above the tree line at its crest, a tall red needle, knifing the sky and seesawing back and forth in the sun. From a distance, if you didn’t know what you were looking at, it resembles the narrow derrick of an oil rig, or the canted boom of a construction site –– but it is in fact, a 75-foot-high metronome, built on a plinth atop a staircase set into a verdant hillside.

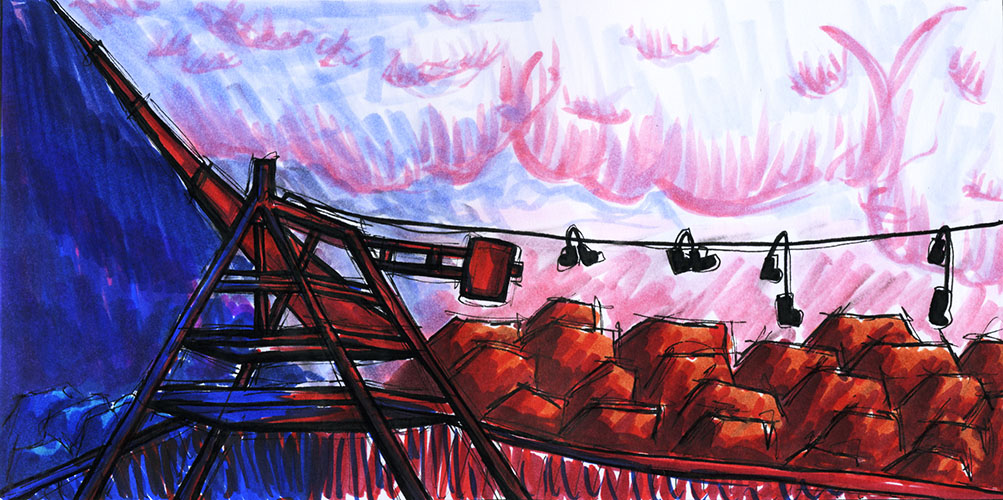

The metronome remains one of the most popular spots in the city. It is a public space, improvised and accessible without fee, where people can hang out and drink and listen to music with their legs dangling over the parapets, as skateboarders powerslide and clap across the stone plateau. The hillside offers a panorama of the city, with its cluster of spires and turquoise domes and baked-clay roofs, and the westward curve of the river, sutured by its many bridges. My first visit to the metronome was on the invitation of one of my students, who was 15 at the time of the Velvet Revolution. As with all my students old enough to remember life at that time, I gently prodded him for details (“What was it like?” “What do you remember most?”), and he told me, as he sat there sipping beer in his True Blue t-shirt, how he’d cried the first time he saw a Madonna concert broadcasted live on Czech TV.

The hilltop spot is still commonly and unofficially referred to by the Pražané (Praguers) as “Stalin,” so named after the titanic 51-foot statue of the old man that was erected there in 1955. For the seven years that it stood, it was the largest monument of Stalin in Europe: centered perfectly in the line of sight crossing the Čech Bridge, the Dear Leader carved in standing granite, hand-in-waistcoat, a proletariat fleet at his back –– also the largest monument to the aesthetic of totalitarian kitsch.

Having been completed just two years after Stalin’s death, the continued existence of the monument was a disgrace until it was unceremoniously dynamited in 1962, well into the Khrushchev era of de-Stalinization. In the same spirit, just a few years before, the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to host exhibitions in one another’s countries as part of a cultural exchange, in which both nations could show off their commodities and present rival visions of the future. In the “kitchen debates,” Khrushchev told Richard Nixon how determined he was to show that the Soviet Union could achieve the same level of innovation as the United States without the superficial force of a consumer economy. One thing he was also adamant about, was that the communist east would not be susceptible to the influence of American soft power, saying (as he sampled a cup of Pepsi): “it’s just a small step from saxophones to switchblades.”

This underestimation of soft power would prove to be a large part of communism’s undoing in central and eastern Europe in the late 20th century. In Czechoslovakia, this could be said to have begun in 1963, when a group of artists and intellectuals from across the eastern bloc gathered for a writers’ conference in Liblice, just outside of Prague, the focus of which was the reintroduction of Franz Kafka’s work into literary criticism, marking the first time since the establishment of social realism that Kafka had been discussed openly in a public setting.

This might be the only time that an academic conference about Kafka could be called “revolutionary” –– because the apparent absence of any retaliation towards this symposium set in motion a growing confidence among the Czechoslovak Writers Union to the point where they proposed that the nation’s artists be allowed to produce material independent of party doctrine, an appeal that was finally heard when Alexander Dubček came to power in January 1968. Dubček, the man associated with the now famous and often appropriated slogan, “socialism with a human face,” was a reformist whose genre of democratic socialism was firmly at odds with the state-socialism model established by the Soviet Union.

To give you an idea of what the country was like at this time artistically, Miloš Forman’s The Fireman’s Ball had been released just a month earlier, Milan Kundera’s novel The Joke just a few months before that, and if you’d had the chance to visit the theater, you could have seen Vaclav Havel’s The Memorandum, an absurd satire on communist bureaucracy. That such great work appeared in such a small country in such a short time and under such circumstances, leaves one wanting for what the Czech New Wave could have been had it not been quelled by an armed occupation.

That spring, Dubček introduced his “Action Plan,” which included guarantees for freedom of expression, freedom of the press, freedom of association, and significantly, a move away from Soviet-style centrally-planned industry towards a consumer economy. The promise of a free press and a consumer society was alarming enough to provoke the Warsaw Pact Invasion in the summer of 1968. The Prague Spring and its subsequent suppression revealed that the Marxist experiment in central and eastern Europe was not much of an experiment at all, but a monolithic dogma that would be enforced from within, with tanks if necessary.

The tanks remained in the streets well into the fall of 1968 and the winter of ’69. In January of the following year, Jan Palach, a student at Charles University, soaked himself in gasoline in front of the National Museum in Wenceslas Square and self-immolated an act of protest against the occupation. This was a grisly coda to a huge moment of huge disillusionment for Marxists in the west, who at last realized that Soviet Communism after Stalin was incapable of reform. The invasion had been a visible mistake, and in hindsight, can be viewed as the moment when the Soviet Union officially took out the lease on the last 20 years of its life.

You can draw a straight line from the events of the Prague Spring to the moment when the people of Berlin first took sledgehammers and chisels to their city’s graffiti-stained partition. Less than a month after the Warsaw Pact Invasion, the psychedelic, proto-Krautrock band Plastic People of the Universe was formed in response to the occupation, giving birth to a new underground of Czech rock music. At the height of state-sanctioned fun, rock bands during this time were required by the government to pass qualifying exams in Marxism-Leninism to be eligible to play, English lyrics were forbidden, and the party went so far as to regulate the length of people’s hair, denying Máničky (the Czech pejorative for “mopheads”) access to pubs, cinemas, and public transportation.

It’s worth mentioning that covert consumer culture was very much alive at this time. Gray market shops called Tuzex, which were known about but not endorsed, sold everything from Marlboro reds to Levi’s. These products could only be gotten with vouchers purchased with foreign currency and were often half the price of a month’s salary. The extent to which people were willing to save for western goods was great. A friend of mine once recounted for me a story about how her mother was the subject of gossip and envy in her village after she bought her newborn daughter a shawl she’d acquired at a Tuzex. Contrary to Khrushchev’s ambitions, the suppression of consumer culture didn’t make people envy their neighbors less, but in fact, made them even more petty and materialistic.

The beauty and resilience of the underground culture during the period of Normalization is hard to overstate. It was emphatically weird: communes, poetry readings, Warholian happenings, experimental music, with denim as the uniform of the dissident. The Plastics performed in houses and found spaces throughout the early 1970s, as a number of their shows were routinely shut down or obstructed by police, and in 1976, the band was finally arrested and tried as “disturbers of the peace.” In direct response to the imprisonment of the Plastics, members of the Prague underground drafted Charter 77, a document formally criticizing the regime for its suppression of free speech and civil liberties, which would circulate clandestinely for years, collecting signatures, considered samizdat by the state.

Many members of the 77 group would eventually coalesce into the Občanské fórum (the Civic Forum), founded and led by Vaclav Havel, and would help negotiate the transition of power after the communist regime officially dissolved in November 1989. Subsequently, many original members of the 77 group found themselves in power the following spring. Poets and musicians became politicians, and Havel was elected as the country’s philosopher-king.

What made the Velvet Revolution velvet was that it didn’t require switchblades after all (saxophones turned out to be enough). It demonstrated the truth of what the French Marxist critic Régis Debray once remarked, that, “There is more power in rock music, videos, blue jeans, fast food, news networks, and TV satellites than in the entire Red Army.” Today, the Czech Republic has more shopping malls per capita than any other country in the European Union. I live across the street from one of them, it has four floors and an IMAX theatre in the roof and its parking lot shares an adjoining wall with the cemetery where Jan Palach is buried.

The revolution was a Faustian moment for many in the Communist Party, when several apparatchiks changed the color of their ties, entered the private sector and sold off much of the state-owned industry to themselves. One of these mafia capitalists, Andrej Babiš, a former pencil pusher of the StB (Czech secret police) is now the country’s second-richest man, as well as the current Prime Minister. 30 years later, the Czechs still love Levi’s and the communists are still in power. Some things, it seems, haven’t changed.

In the years following the revolution, the bomb shelter beneath the Stalin monument became the location of Czech pirate radio and later transformed into one of the city’s first rock music clubs. The metronome was erected in 1991. Power is written into the landscape of cities, and just as the basilica of Sacré-Coeur was erected on Montmartre by reactionary monarchists as a symbol of France’s repentance for the Paris Commune, so too is the Prague Metronome a symbol of the triumph of soft power over the forces that sought to suppress it.

What it actually means is perfectly ambiguous: the music that soundtracked the revolution, the ping-pong of the new democratic process, or the steady resilience of the Czech people during 41 years of communism. As the needle rocks back and forth, it sets the tempo for the whole society, one that governs the rhythms of the changing political order, which no regime can outpace for very long. After all, “containment,” as it was originally conceived, as a diplomatic philosophy rather than a military strategy, was one of running out the clock –– to keep the threat within the walls long enough to allow internal change to begin. Politics, as Pierre Trudeau said, is all about timing.

Today, the metronome is a public space. It belongs to no one, and people are free to do with it as they wish. These days, however, the needle is idle, stalled to the right, perhaps in further symbolism of the direction Europe is heading nearly 30 years after its glorious revolutions. •