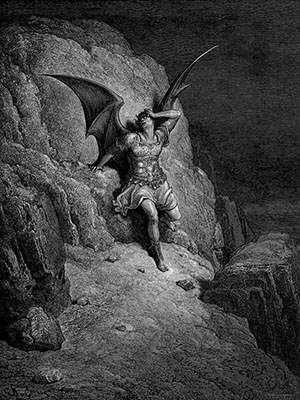

My hero is fearless, proud, resolute, farseeing, self-sacrificing, and profoundly engaged in the struggle against tyranny and oppression. He’s also several hundred feet tall (when he wants to be), does celestial cartwheels when flying between the earth and sun, can turn into a cormorant when occasion arises, and despite his onerous responsibilities as a leader of men, manages to be pretty good family man, though his spouse is Sin and his offspring is Death. He speaks some of the most beautiful English ever composed, even when just muttering to himself. He’s John Milton’s Satan.

I don’t say he’s perfect. He’s a bit of a snob, somewhat lascivious, and, gravest of all, willing to harm innocent third parties in his battle against injustice. In truth, you can easily load the dice for or against him depending on how you select the evidence, and readers have been selecting the evidence ever since Paradise Lost was first published in 1667. Some scholars contend that this debate has outlived its usefulness, that the war between the pro-Satanist and the anti-Satanist camps reduces a great and complex whole into a distorted and schematic dichotomy. They may be right. Then again, why should you read Paradise Lost as a boringly contextualized treatise in early modern “energies” when you can read it as a splendidly baroque science fiction with one of the most fabulous bad guys in all of literature?

Because you might be misreading it? No doubt. And yet if a sober, dispassionate reading of Paradise Lost entails carefully weighing the claims and counterclaims of that petulant, treacherous, and sadistic autocrat who passes for God, then a sober, dispassionate reading would seem not merely misguided but contemptible. I can certainly see why some readers might resist Satan’s magnetism. He is, after all, the devil, and as the poem progresses Milton steadily darkens Satan’s allure until, as early as Book IV, we find him “squat like a toad” at Eve’s ear. But God the Father, whom the rebel angels quite properly term the Thunderer and the Torturer, is bad news from start to finish. What kind of God spends all of eternity devising tortures for his enemies and then blames them for mistakes he has always known they would make? Well, no one has ever solved the problem of theodicy, least of all John Milton, who, as William Blake famously observed, was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” The problem with God in Paradise Lost isn’t so much doctrinal as tonal. Does this sound like the benevolent patriarch you’d want to sing hymns to in heaven unless compelled to do so on pain of expulsion and eternal torment?

For man will hearken to his glozing lies,

And easily transgress the sole command,

Sole pledge of his obedience; so will fall

He and his faithless progeny. Whose fault?

Whose but his own? Ingrate, he had of me

All he could have. (III, 93-8)

Admittedly, a reading of Paradise Lost that deifies the devil and demonizes God would seem to depart somewhat from the poet’s intentions. But not entirely. William Empson, whose Milton’s God I regard as a work of genius scarcely less audacious (and sometimes rather more fun) than Paradise Lost itself, remarked that Milton “could not have made God automatically good in the epic; God is on trial . . . and the reason is that all the characters are on trial in any civilized narrative.” Furthermore, Milton, the rebel propagandist and regicide, was to Charles I roughly what Satan is to God: an inveterate enemy to established authority. Is it so hard to believe that Milton’s anti-monarchical principles might have informed the characterization of his tortured antagonist? Milton’s failure to justify the ways of God to man is precisely what makes the poem so fascinating. And the most fascinating aspect of that failure is the psychologically nuanced portrait of Satan, an all-too-human personality, notwithstanding his ability to turn into vapor or, in a pinch, invent gunpowder.

Perhaps his most human moment is the soliloquy on Niphates’s top in Book IV, when he spies Eden for the first time and has what we might call a nervous breakdown. (“Thus while he spake, each passion dimmed his face / Thrice changed with pale, ire, envy, and despair.”) Although Satan gives God more credit that he really deserves, in his honest reckoning of mistakes made and opportunities foreclosed, he correctly perceives that there is no going back (“therefore as far / From granting he, as I from begging peace”). Here, as elsewhere, you can choose sides and muster sufficient evidence either way. What interests me is not the strength or weakness of Satan’s argument but the pathos of his suffering. There’s no right or wrong about it. Like anyone who has been traumatized by loss, Satan is imprisoned in his own mind, and all the reasoning (or therapy) in the world won’t open the bars. He does have the consolation, however, of being able to express his sorrow in sumptuous blank verse:

Me miserable! which way shall I fly

Infinite wrath, and infinite despair?

Which way I fly is hell; myself am hell;

And in the lowest deep a lower deep

Still threat’ning to devour me opens wide,

To which the hell I suffer seems a heav’n. (73-8)

What does open the bars at least a crack is his resolution to act. True, that action will doom the human race to death and destruction, but given the insipidity and servility that Adam and Eve must endure in Paradise, it could be argued — indeed, the traditional theological concept of felix culpa does argue — that Satan does our First Parents something of a favor. Anyway, if “goodness” means what God the Father says it means — enforced ignorance, rigid obedience, and rule by arbitrary diktat — then Satan is speaking almost a literal truth when he says, “Evil, be thou my good.”

“The Prince of Darkness has only chosen this path because good is a notion defined and utilized by God for unjust purposes.” So wrote one existentialist hero — Albert Camus, in the Rebel — of another. Like any good existentialist, the Prince of Darkness is thoroughly engagé. And while his freedom of action is severely limited — destroying the human race is, basically, his only option — he chooses his destiny to the extent that he can. The results are less than ideal for him and for us; such are the determinants of the Absurd, which the world created by you-know-who certainly is. Of course, Satan can only lose. If he didn’t know his adversary was omnipotent before the war in Heaven, he sure finds out. But maybe like Camus’ Sisyphus uselessly rolling his rock up that slippery hill, Satan transforms futility into a sort of fulfillment. “What though the field be lost?” he declaims to his disheartened troops after their rout:

All is not lost; the unconquerable will,

And study of revenge, immortal hate,

And courage never to submit or yield. (I, 305-8)

Some of this is soldierly bluster. Some of it is intended to cheer himself up no less than them. But all of it strikes me as an ethically and psychologically acute response to the vastation he and his have suffered. In bringing the fight to his unconquerable oppressor, Satan at once keeps the notion of justice alive and finds a field of action commensurate to his spiritual needs. Do I wish he could have formed a grievance committee to adjudicate his claims more peaceably? Yes, I do. But if the Almighty had seen fit to create a just world, the Prince of Darkness might not have needed to go to such lengths to salve his psychic wounds and to succor his myriads of demoralized followers — comprising, it’s worth noting, a third of the population of Heaven. Clearly, God’s reign of sweetness and light left something to be desired.

In speaking up for Satan, I’m reminded of the photojournalist played by Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now, who, expiating on the mad genius of Colonel Kurtz, nevertheless finds it necessary to explain to a stunned Captain Willard the presence of all those loose heads lying around: “The heads. You’re looking at the heads. I, uh — sometimes he goes too far, ya know — he’s the first to admit it.” Well, yes. I wish life were less painful, I wish we lived longer, I wish lions and tigers were happily vegetarian, which they were until the moment Satan persuaded Eve to take that bite and “Earth felt the wound.” But really, would anyone want to live forever in that pastel-colored stasis that Milton imagines as Paradise? It’s true that Adam and Eve are heartsick over their expulsion, but maybe they just haven’t had time to get bored yet or maybe they’re shocked at the way God keeps piling it on. “O unexpected stroke, worse than of death!” Adam exclaims when the Archangel Michael informs him that, in addition to receiving sentences of hard labor and death, they are now to be evicted from the only home they have ever known. Paradise has its attractions, and I especially like the way the ramping lion “dandle[s] the kid” in his paws, but it becomes a lot more interesting after the Fall.

Suddenly Adam and Eve are obligated to become what they had not been before: autonomous adults willing to accept, not without some kicking and screaming, the burden of freedom. Satan, in a way, is their intercessor, who delivers them from the gilded cage that allows of no moral development. It’s no accident that they have their best sex after they’ve both tasted the forbidden fruit, though they pay for it afterward with guilty recrimination; welcome to our world, where the disturbing underside of sexuality is never too far from the surface. (The obedient angels, by the way, are gay; the Archangel Raphael blushingly admits to Adam that they enjoy the occasional half-corporeal act of interpenetration.) Satan, too, feels the sting of desire — “Among our other torments not the least, / Still unfulfilled with pain of longing,” as he describes it. Adam and Eve have a massive fight in Book X that sounds, apart from the stupendous rhetoric, like a bad morning after anywhere the world over. (It might also have sounded rather like the household of John Milton; he wasn’t the easiest of husbands.) And that to me is the glory of Paradise Lost: that for all its baroque splendor and visionary intensity, it remains anchored, like the best science fiction, in human realities. In Satan, more than in any other figure in the poem, Milton concentrates those realities: the agony of dispossession, the struggle of self-mastery, the demands of leadership, not to mention a full plate of rage, resentment, and sexual frustration. And it’s not just that Satan is good because God is so bad. Satan’s goodness is compromised, but unlike his appalling adversary, the Prince of Darkness shows us a way forward. How right Baudelaire was to gather all of his balked spirituality into an ecstatic prayer (“Les Litanies de Satan”) addressed to the damaged deity who comprehends all human distress: “O Satan, prends pitié de ma longue misère!” •

Images courtesy of Georges Nijs and Andrés Alvarez Iglesias via Flickr (Creative Commons)