There was an older man at a dinner party, relaying the history of his marriages. His first one, he told us, was a disaster. He was too young, she was too young. It lasted only a few years and then it ended angrily. He thought he’d never remarry, but then he decided he wanted to have a child. He married another woman, who turned out not to want children, but, he assured us, he eventually “wore her down.”

There are all sorts of struggles that take place within a marriage. Conflicting desires create situations without the possibility of compromise and so one partner tries to overpower the other’s will. Wives do this as well as husbands. But there was something about the way the story was told that caused the women at the table to immediately exchange worried looks and inhale deeply at the words “wore her down.” He wanted a child, but for that he needed a woman’s body. He procured a woman’s body, and when that body was not compliant, he forced compliance through manipulation and control. The man was a writer, and so I am making the assumption that he told this story with a particular intention and that that intention could be analyzed. I understand that this is probably unfair.

The wife is very often a problem in stories, whether they are told in movies, books, or just dinner party anecdotes. The words “my wife” set my teeth on edge, said so often in the same tone of voice as a man might say “my car” or “my phone.” The property label often trumps her own name – why do you need her name when the most important thing to know about her is her association with me? And so wives in stories are metaphors, representations of domesticity, or adjacent to the real actors: the husbands. Who almost always get names.

But the dead wife is a particularly nasty trope in storytelling because so often her life is sacrificed directly in service to the story. She is there only to die. The dead wife movie shows up again and again. Even in the past decade or so, there’s been, and this is a selective sampling, Southpaw, Crimson Peak, Shutter Island, John Wick, Looper, The Road, The Fountain, Inception and every other movie Christopher Nolan has ever made. On television there’s Feed the Beast and Jessica Jones among others. In the comic book world, the dead wife is so prevalent she gets a cute little nickname: fridged. As in, the body of a man’s wife, traumatized, murdered, and shoved in a refrigerator, sets her husband off on his heroic quest of vengeance.

In almost every case, the wife is a catalyst, not a character. She is there to provide the man something, and that thing is a story of redemption/self-discovery/healing/whatever. Because if a spouse is just there to give you some thing that you want, there’s no one more compliant than a dead wife. She is not a person, she is a conduit. Her body serves a specific purpose. Grieving over her gives her husband depth and vulnerability. It gives him something to do.

A particularly egregious example of this is the recent Captain Fantastic, a film that had been well reviewed as a beautiful depiction of a grieving man’s relationship to his children instead of what it seemed to me to be, a story of two men fighting over a dead woman’s body. In Captain Fantastic, the death of Ben’s wife, Leslie, sets him and his children on a long-delayed collision course with the outside world. He and his children (and presumably his wife, although she was hospitalized for bipolar disorder some time before her suicide) have been living in the wild, like the Swiss Family Robinson meets survivalist Paleo-Marxists. The family hunts and gathers their own food, builds their own shelter, and participates in daily grueling physical training.

After his wife dies, Ben, played by Viggo Mortensen, and his six children travel across the country to enter into open battle with his father-in-law for the property of this woman. There are two competing stories for who Leslie is. In her father’s eyes, she is their good Christian girl who went astray when she met the demonic force of her husband. In her husband’s eyes, she’s a radical Buddhist railing against her consumerist, capitalist family. Her father buries her in the family plot. Her husband and children dig up her corpse and burn her. Her father files for custody of her children. Her husband attempts to kidnap his own son. His father tells his version of his daughter, her husband tells his. The battle for ownership of this woman and her offspring goes on and on.

What Ben, and the Captain Fantastic screenwriter and director Matt Ross, get from this dead woman is a furious self-righteousness. Ben’s merciless parenting (while rock climbing, one of his sons badly injures his wrist; Ben tells him there’s no one coming to rescue him and forces him to continue to climb with his bad hand) is shown to be vastly superior to “normal” American parenting. When we meet his sister’s sons, they are pudgy, video game-addicted mouthbreathers, and Ben taunts them by showing off his children’s superior intellects. His children, fit and strong, see the fat people of a city and ask their father innocently if all the people there are sick. Thanks to his wife’s death, Ben gets to triumph over the society he rails against.

What’s missing from the film is Leslie herself. She is dead before the movie even begins, and she appears only in fairy-like visions to her husband. But his image of her, of a laughing redhead with her hair always obscuring her face, lines up in no way with the stories the men on the screen tell of her. Her son remembers her as angry and sad, her father remembers her as a fragile girl, her husband remembers her as a revolutionary/giggling ghost. When the children say her favorite song was Guns N Roses’s “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” that seems incongruous with absolutely everything anyone said about her before that point. It’s not clear if even the screenwriter had a clear idea of who this woman was, as all of the mentions of her clash and stubbornly refuse to cohere into a character. She remains a series of unconnected tics and eccentricities. But then why take the time to create an identity for her if all that matters is how she relates to the men of the story? Her death isn’t even what causes the family’s crisis, it merely sets up the real battle, which is the cloistered family versus the outside world. The family adapts immediately to her loss, she seemed to perform no essential function in their home. Their routine continues unchanged.

Captain Fantastic, then, manages to fall into every dead wife movie trope I can think of. She’s not nameless, but she’s missing an identity. Her death sets her husband off on a hero’s journey and mission of vengeance. Leslie may not have been fridged, unless you want to count a husband’s indifference to his wife’s mental illness as a form of assault (a long history of mental illness is alluded to, but no one discusses how the hormonal imbalances of six closely spaced pregnancies, more if there had been unmentioned miscarriages along the way, may have further destabilized her condition), but from the title to Ben’s bright red suit to the story arc, this is a superhero tale. And Ben is the superhero, not her.

I don’t believe that entertainment has a direct influence on society, that violent movies beget violent actions. But I do think the stories found in entertainment can either reinforce or challenge the stories we tell ourselves about how the world is. I don’t think this writer at this dinner party saw too many movies where women were not bestowed with humanity or agency and therefore he felt he did not have to bestow his wife with humanity or agency in her decision not to have children. But I do think one of the reasons Captain Fantastic was so well reviewed by film critics is because it reinforced their stories about who they are. As in, by being intellectuals, by being critics of consumerist culture (even while definitely participating in it), by valuing theory over video games, by being on a paleo diet, they are superior to the fat, uneducated masses in flyover country. I won’t conjecture the power dynamics of these men’s (as a wide majority of film critics at major outlets are men) marriages that allowed them not to see the dead wife storyline as a problem. Except silently, to myself.

Louder than Bombs, the first English language feature by Norwegian director Joachim Trier, shares many of the same basic story components as Captain Fantastic. There’s a wife and mother who is already dead as the movie begins. She killed herself. A father and son (and then a former lover) fight over who owns her. And yet Louder than Bombs actively resists every dead wife trope that Captain Fantastic enthusiastically embraces, challenging the traditional stories of who a wife is and who the most important person in the story of a marriage is.

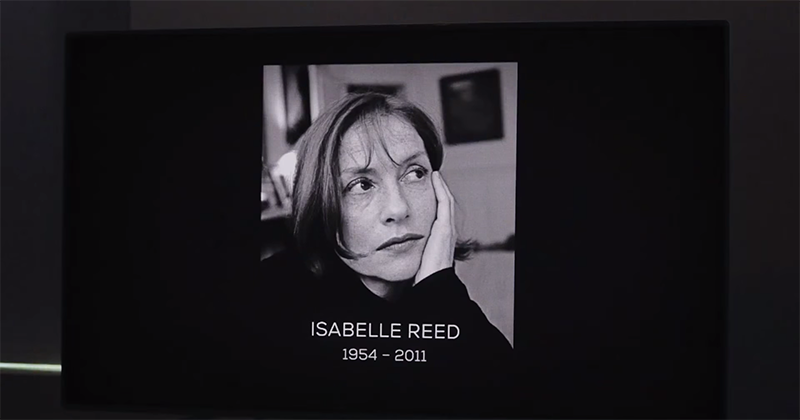

The death of war photographer Isabelle, played by Isabelle Huppert, sets her husband Gene (Gabriel Byrne) and her sons (Jesse Eisenberg and Devin Druid) on similar quests of self-discovery, but instead of being revealed as heroes, the discovery is their own mediocrity. Isabelle was the force that gave their lives meaning and glamour, and now that she is gone, they are forced to confront that.

No giggling ghost, Isabelle is a formidable presence even in death. We first see her in an interview with Charlie Rose, discussing her life’s work of photography in war zones and areas of conflict. A gallery is organizing a retrospective, and they are editing together a memorial video tribute. Gene seems uncomfortable with other people’s claims to his wife. When her colleague tries to show him the prints that will be on display, Gene fidgets and checks his watch. Everyone at the gallery is in awe of Isabelle, even the video Charlie Rose, of her strength and bravery. But that world, the outside world and the art world, is something Gene only had access to through Isabelle, and without her he seems deeply uncomfortable.

There is a flashback scene to when Eisenberg’s character Jonah invites his mother to one of his college parties. All of his friends are captivated by her; they encircle her, hanging on to her every word. Jonah basks in the glow of his mother, beaming back at her with admiration and pride. His association to her is one of the few things he has going for him. After her death, Jonah becomes, or is revealed as, a cliché: a sociology professor with a superiority complex, a man who cheats on his wife soon after she gives birth to their daughter. Similarly, as Gene attempts dating again, he goes for a school teacher, nice enough but considerably younger than either himself or Isabelle.

Isabelle dominates the story, even in death. This is the story of a dead wife and the men she left behind, but she is a character, not a catalyst. Every man must renegotiate their lives based on what they lost when they lost her. For Gene, she was an infuriating but dynamic presence, his one hope at resisting the comforting pull of domestic suburban life. For Jonah, he was the satellite that reflected the light of her star, and he tries to get that back by organizing her archive. For the youngest son Conrad, she was still a mostly physical presence, a source of comfort and softness. Each has to deal with the crater her absence has created in their lives.

While the men squabble and posture over who knew her best, who had the most access to her, who she truly belongs to, Isabelle remains her own person. In one gutting scene, Isabelle looks directly into the camera in a close-up, making eye contact with the audience with an expression of compassion and strength for ten long seconds. This is in stark contrast to Captain Fantastic‘s Leslie, whose face is obscured by shadows or her own hair for the entirety of the film. Her husband won’t share her, not with her parents, not with the world, not even with the audience. She is mine, the film says.

It is interesting, though, that the film trailer for Louder than Bombs presents the traditional dead wife storyline. The wife is dead, the husband and sons are catalyzed to action and self-discovery, the wife remains silent throughout and haunts the screen as a specter. It’s presented as a film about men. One wonders at this decision, unless it is simply that someone in charge assumed an audience would be more drawn in by stories about men.

After the dinner, I went searching out the writer’s novels. I just wanted to see how if the wives in his fiction fared any better than his wife in his story. From what I could find, flipping through his books while sitting on the floor of a bookstore, his narrators had rich inner worlds, and the women they met had almost none at all. They remained mysterious to the narrator and apparently to the author. They were there to set action in motion, not to be agents of action themselves. It makes a girl miss someone like Tolstoy. Sure, he was a brute to his wife, but his female characters are iconic.

It would again be deeply unfair of me to speculate how, say, the married life of Captain Fantastic writer Matt Ross might be going. Or the writer of Southpaw, who created a wife character who had no life outside of her interactions with her husband, and was murdered to give her husband an interesting narrative. Or what exactly is going on with Christopher Nolan that he can’t create an interesting protagonist without giving him a dead wife to torment him. (And who can’t seem to find any woman interesting unless she is dead.) And yet in my darker moments, I wonder. •

Screen captures taken from the trailers for Captain Fantastic and Louder than Bombs.