British midshipman literature set in the late-17th and early-18th centuries makes you feel like you’ve entered into an exclusive club, one which is nonetheless open to anyone who comes along and cracks the spine of the latest high seas adventure of a young man in flux.

A midshipman at the time was apt to be a 16- or 17-year-old boy who joined the King’s Navy with the expectation — or hope — that he’d eventually progress to lieutenant, and from there, if all broke well, to senior lieutenant, and on to captain.

This boy immediately took up a role as what we might now think of as management on these ships. The bulk of the crew were career-long sailors who could neither read nor write. Many of whom were victims, at one point, of England’s notorious press gangs, seized into service when they were drunk and stumbling home from the pub.

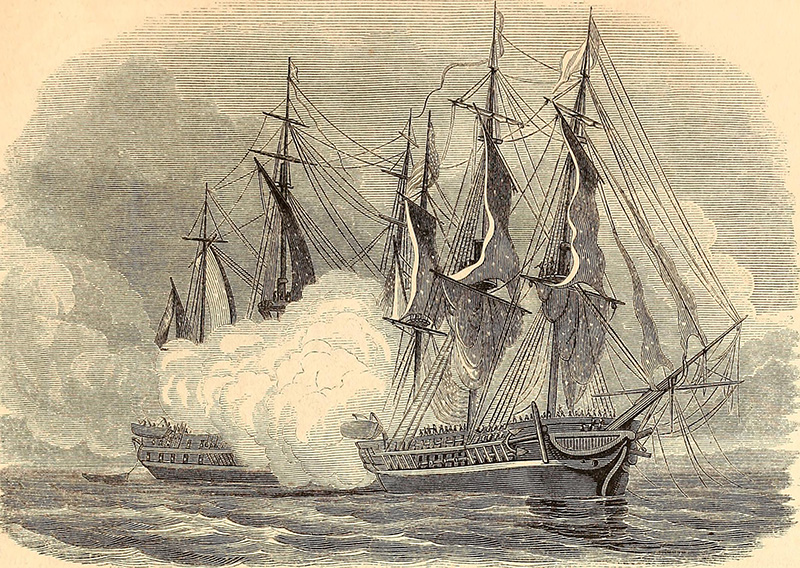

At which point, the King now owned you, and you would do his royal bidding at sea where you were likely to be impaled by a sliver of wood, flung from the rigging, ran through with a sword, or roasted in a fire. To compensate for the attendant risks of the job, you’d be plied with rum, and inebriated throughout most of your days.

A midshipman was certainly literate, and as a boy in charge of hardcore men of the sea, matters could get dicey. This was the age of the Napoleonic Wars, and the midshipman faced the same dangers as everyone else on his particular frigate, only now he was in a leadership role for the first time in his life. At the same time, he was tasked with learning the ways of the sea, the mathematics of navigation, the mores of his captain, and being but one of a number of midshipman, the more senior of whom could make his life miserable.

Since my early 20s I have been a reader of the literature that grew out of the midshipman’s lot in seafaring life. In a sense, it’s a coming of age genre, but with a couple of major paradoxes that render this strand of literature unique.

Consider something like C.S. Forester’s Mr. Midshipman Hornblower from 1950. Forester was tantamount to the Grand Admiral of naval fiction. As much a historian of the sea as a storyteller, he encountered a World War I memorial with the name Hornblower on it. Having an ear for a sonorous name and a penchant for Shakespeare, Forester then applied the Christian name of Horatio. Upon having learned everything one might learn about how a ship of the line functions — and we are talking crazy amounts of details and specifics — he commenced his series of novels about the prodigy who still gets seasick when his ship is docked in a harbor.

The books aren’t quite as well-known as Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin series, but I’d rate them as better, putting you as squarely upon a captain’s quarterdeck with a gale blowing in as surely as if you stood there in the flesh, the mist dampening your neck and the brine wafting beneath your nose. The O’Brian novels detailed a friendship, and that was their focus, with the appurtenances of naval life heavy in every paragraph. With Forester’s Hornblower series, though, the primary relationship is between midshipman and this nautical world, which in turn makes for a relationship between what he has been and what he fights to become.

What’s especially telling about Forester’s efforts is that he didn’t write Hornblower’s story chronologically. That is, we don’t begin with him coming aboard his first vessel on his first day as a newly minted midshipman.

The upshot is that Forester buffs like to debate whether you should read the series in the order in which the books came out, or the order in which we can chart Hornblower’s career from day the first, to day the last. His life as ship’s log, as it were.

The series begins in 1937 with Hornblower in command in The Happy Return, a novel in which he has to deal with a Spanish revolt cooked up by Napoleon. The French despot is the Professor Moriarty of these stories, almost always embroiling in his evil ways from offstage. A fine work, but not as successful as the midshipman saga that would follow 13 years later.

My sense is that Forester in the 1930s hadn’t figured out quite how to compose a story in which a boy is also a man — as much one as the other. This isn’t about coming of age so much as being, in part, fully formed and, at the same time, largely inchoate. One of those aforesaid paradoxes. For that is the catch with the best midshipman literature: that 17-year-old, pressed into his own kind of unique service, is both of his age and station and, in a sense, of our age and station, no matter where we may be as adults.

The notion of being something redoubtable, and still needing to progress, is perhaps the ultimate catch, too, of adulthood, the rock on which so many people founder. So now we have a literature of youth, in part meant as a means in which to chart a course through later years. A different make of ship’s model.

There is an excellent A&E Hornblower TV series from the late 1990s that documents many plot points of the midshipman novel in two episodes, The Duel and The Fire Ships. The teleplays are remarkably loyal to the book, which you’d not expect when you read it. The pace isn’t so much fast as fragmented, if such a remark might be made about pacing. One vignette passes into another, like a short story has been laid atop a short story atop a short story, and then dropped in a cask of sea water to blend it all into something total, whole. Hornblower has something of a vision when terrified up in the rigging, knowing he must advance and yet being unable to do so until his mind has mastered the situation. That the takeaway point is that some situations are impossible to master intellectually is what frees him up to move once more, to put head down and grind, as we might put it in modern parlance, and gear up for what is next.

The other Hornblower novels don’t read this way. They are more through-composed, to use a musical term, and cycle back less with this repeated pattern of mini-stories that reprise aspects of the ones that came before. That becomes manner of nautical pedagogy, a series of lessons set on the sea for the purpose of a sped-up internal evolution. Lest this particular man go under, so to speak. Forester is giving us the world through the eyes of one quite not ready to master it as he is becoming adroit in mastering parts of it. Which, of course, is about all you can hope for, whether you’re a teenager or a septuagenarian. We all know a cliché like “age is but a number,” but think about the people you know in your life, over the course of your life; how many of them are that different from who they were at 22 to how they were at 30 or 50? So often people become what they’re going to be and stop. Life factors change, jobs change, partners change, living situations change, there are physical changes — but growth tends to be exchanged for something that’s more like settling in, hunkering down in an identity.

This doesn’t happen with the best midshipman writing, like with Forester’s Hornblower chronicle, and in that way the literature is most instructive. There’s a metaphorical aspect at play — if a midshipman like Hornblower doesn’t progress and evolve, he’ll die, conceivably, or not advance in his career, certainly. These are maritime realities, but they’re also potent allegories for us back in the mainland, in our own lives. Will you die if you don’t grow? Not in the put-him-in-a-box sense. But it’s interesting how easy it is to fall into a pattern of existence rather than what Hornblower encapsulates as a quest for living. He speaks often of duty, what one is tasked with by something beyond one’s self. There is a duty to the bildungsroman spirit throughout, to extend that idea of always being formative and in-flux into the world of adulthood. The child never stops fathering the man, if the man is to get anywhere.

A second paradox is the manner is which a stylized mode of communication fosters both fealty and humor. If you’ve read something like Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, you’ve likely walked around for a few days with the phrases of his characters at the edge of your tongue, poised to become part of your vernacular.

It’s the same way with Mr. Midshipman Hornblower, where no matter what the crisis, no matter if you’re bleeding out on the ground, those above you must be addressed with a “sir” at the close of every sentence. You have a musket ball in your side and your fellow midshipman has just had his brains pasted on the deck? When the lieutenant approaches asking if your colleague is unfit to perform his duties, you respond composedly, and with that sir at the end of your sentence.

The idea is absurd, but from such absurdity comes much laughter, as someone like Beckett well knew. You’d expect him to be a fan, and Forester’s prose rhythms in the dialogue sections are not far afield of what we find in mid-career Beckett. Hornblower, a stiff, awkward boy when he comes abroad, has no problem with these codes of language, and from that shared patois he begins to find his place among these men and to find his place with himself.

The reader picks up on the terms, finds his or her own place within the novel and the lives of these invented characters, and it’s as if a great wind has come along to fill everyone’s sails and push the collective forward, each in their own lives and duties. All of that, and you also get rip-snortin’ action that will have you ducking underneath your covers as you read, lest a cannonball tear off your head.

Alexander Kent — who was actually Douglas Reeman — was a next generation Forester, with his Richard Bolitho: Midshipman, coming out in 1975. This new upstart naval hero was more of an Errol Flynn type, with a love of the ladies. There’s a greater emphasis on action over emotion, but the hallmarks remain.

You can come away with a veritable degree in maritime terminology in reading books in series like the Hornblower and the Bolitho. We beat to quarters, listen to the bosun, fear lee shores, tremble at prospects of the cat, pace the fo’c’s’le. That specificity and level of detail — and years must have gone into learning all of it — basically underwrites the drama that follows, grounding us in realities from which new ones will spring.

Bolitho is dashing and confident where Hornblower is deductive and Socratic, and, despite their dissimilarities, if you do like one, you’ll probably like the other. They are full-fledged, well-rounded characters, but their true master is this idea of being both solid and disassembled at once, and trying to progress through that paradox with the help of language, a developing sense of duty, and evolving modes and depths of character which ultimately makes these characters so memorable. So Polaris-like, even, in terms of where we might look for hints for ourselves into matters of language and character.

Bolitho’s evolution tends to have more of an element of the past than Hornblower’s. Stepping into the breach is his modus operandi. That is his clarion call. And while the purpose of heart is admirable, Bolitho is a character possessed of sufficient self-knowledge to know there are gaps in his internal education that are at times widened by his “act first” nature. He is a most course-correcting midshipman, though, as any midshipman needs to be, and whereas Hornblower mulls with a depth of probity before acting, Bolitho grows by doing so post-action. Language fleshes out character, and once more we see a touch of the Socratic on the high seas.

But speaking of language and character: one cannot depart from a conversation on this stripe of literature without mentioning Frederick Marryat’s singular volume, Mr. Midshipman Easy. Again, the hallmarks are in place, but there is no midshipman like this particular fellow in the whole of the genre.

Marryat himself was a distinguished man of the sea who rose all the way to captain, and then resigned his commission to — get this — be an author. As it were, Mr. Midshipman Easy is one of the earliest novels of this type we have, being published in 1836. The author is nearly contemporaneous with Horatio Hornblower the character.

One might think that Marryat would be a kind of prose martinet, as captains weren’t exactly known as funny guys, but this is one of the most hilarious books I’ve ever encountered.

Easy is a cad, and also something of a proto-Communist, believing that there is no such thing as private property, never mind that he’s spoiled and comes from a family where he was quite the little lord.

Once more we have the sing-song qualities of that formal language that become less formal, more inclusive, more musical through repetition. A sea-based recitative. But Easy adds his own layer to all of this. His shipmates don’t know what to make of him, and when they confront him on his latest weird take on matters, he utters what becomes his standard refrain: “Let us argue the point.”

And boy does he then argue. He’s akin to Bloch in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the character the narrator takes home meet his family. They enter the house from out of a pouring rain, absolutely drenched, the narrator’s father asks Bloch about the weather, and Bloch says he’s so beyond earthly things that he could not tell, in a way, if it was raining. That’s Mr. Midshipman Easy.

He’s what I think of as a verbal romper, entertaining himself with jokes that go over the heads of his crewmates, while making different points at the same time. Challenged with a problem of arithmetic, say, by a superior, Mr. Easy will work every secondary level of meaning in the language to go completely off topic and answer something else entirely. He’s the kid in class who was too smart for his own good, and who knew how smart he was. Or thought he was, anyway. You kind of want to see him get his comeuppance, but in a gentle way, as one does with, say, Willie Baxter in Booth Tarkington’s Seventeen. Same age group, in one way.

But Easy’s verbal acumen puts him well beyond that age group at the same time, but again, we have the idea of being both established and perpetually in-process. Easy’s intellect is more showy than Hornblower’s — he is smarter than his peers and full well knows it. Thus, he has his own waters to navigate, as does anyone who is smarter than their boss has theirs.

Mr. Midshipman Easy does get his comeuppance, and it is one that he readily gives in to, having argued the point, charmingly, with himself. That reconsideration is tantamount to a fresh breeze in the sails: the prospect of movement is now at hand. For these midshipman, a lived life is a series of re-starts and being able to re-start. Battles provide opportunities in these matters, true, but again, what is occurring internally with each of them is every bit as pyrotechnical as what is happening on the main deck, and it’s happening faster. This is a lad who, clearly, will serve himself well, even when he is not well-served by life, should that come to pass, as it always does with a life under sheet and sail. And we are all under sheet and sail in some manner or other.

To knuckle the forehead to one’s superior is the way of this naval world. But to knuckle the forehead to one’s evolving self is the salient directive and lesson of midshipman fiction. The sea, as any non-lubber knows, simply provides a mirror. •

Feature image courtesy of US NAVY via Wikimedia Commons. Article images courtesy of US NAVY, Financial Foundation Collection, and Internet Archive Book Image and CircaSassy via Flickr (Creative Commons).