My favorite moment when visiting any art museum is leaving it.

While I’d claim to enjoy viewing art, two to three hours strolling through most collections can give me museum fatigue. Stepping out on the street, however, I gawk astonished on the colors, forms, and composition of everyday objects. Traffic light, mini-skirt, trash can, movie poster, hubcap, a wad of gum: suddenly the world’s transformed, exposed. I feel like the kid with X-ray specs from the ad at the back of comic books. The luster and lineaments of ordinary artifacts take on giddy energy as if the hand of an estranging god were shaping a terrible beauty before my eyes.

The first time I remember this experience was during my high school years. The suction of the revolving doors slurped shut as I exited MoMA. The brisk autumn air of Midtown slapped my face. Dusk-light reveled on the iridescent cloud scud, and I stared down the crevice between office towers where every window was awash in flame. The monoliths seemed marshaled from glacial shadows. As I pressed through the urban vortex of faces, freaks, and fashions with a friend on whom I had a crush, a gulf of freedom opened in untold directions. On a lark, we’d taken a Greyhound several hours that morning. Now we wandered lost in the grid of nighttime Manhattan. I wasn’t from a small town; I was from a barren field, a clod of dirt. To my young, provincial eyes, the city in its madcap flux appeared a vast network of creation, a quasar emitting the voltage of a trillion stars and warping all the space around it.

Oscar Wilde in “The Decay of Lying,” describing a similar phenomenon, goes so far as to posit that art is truly making, that it originates nature: “There may have been fogs for centuries in London. I dare say there were. But no one saw them, and so we know nothing about them. They did not exist until art had invented them.” Until Wilde had been quickened by the sensibility of the Impressionists, he had failed to see the fleeting, fogbound reflections on the Thames. Before Monet, the delicate glints and glooms of sunsets had no tractable suasion on the mind. The allure of the humdrum weather had been beclouded in Wilde’s dim, untutored eye. Gazing on a painting had winkled dazzling vapor into existence through some quantum leap.

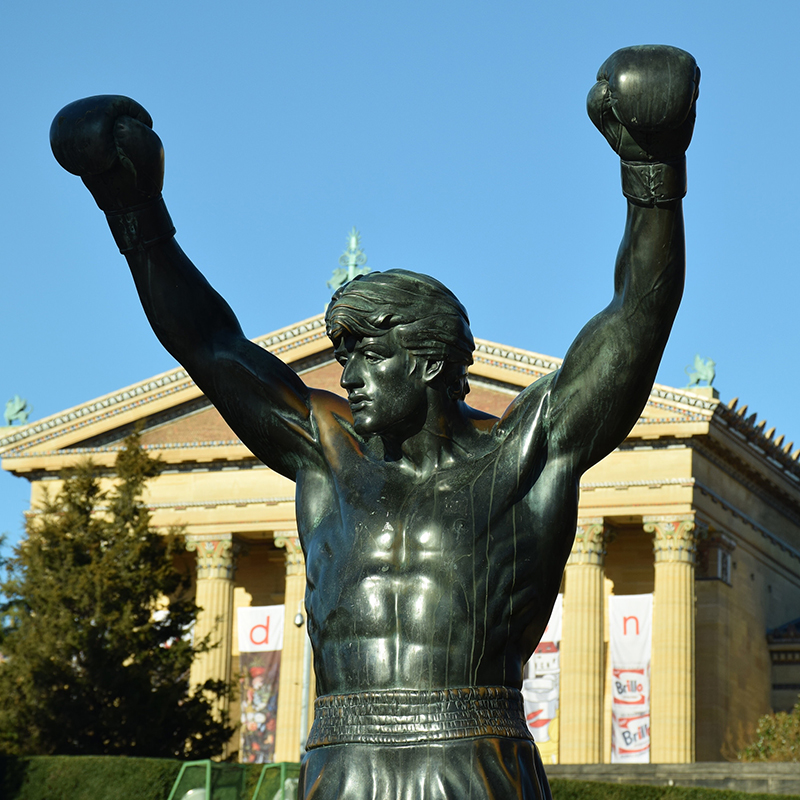

As a college student, a couple of years after my visit to MoMA, I took the train down to Philadelphia. I was in a Modern Art class; an assignment dictated a museum visit. The steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art — made famous from a cheesy, triumphal training scene in Rocky — loomed before me. If good art could help us see, I wondered, could mediocre art obfuscate? I couldn’t look at the long ascent of steps without imagining the film, thus reducing real life to a movie set. If Wilde’s Impressionists disclosed the fog he had been in, then Rocky trapped me in celluloid.

For some people, I suspected, reenacting a moment of cinematic drama adds a bit of glamor to their day. The montage depicts the literal ascent of a blue-collar hero whose hard work affords him a proprietary vista atop the city, a primal scene inscribing the myth of the self-made capitalist man. The imitation of Rocky’s training montage is later incorporated into a sequel, Rocky Balboa, when the closing credits portray assorted Philadelphians recreating the by-now iconic shot. This vertiginous simulacra of mimesis is not unlike Bob Ostertag’s anecdote about a gay porn star who can’t get hard on set unless he first watches porn. So much of our experience is mediated by the objects we consume. The structure of sight and the shape of desire is manufactured by the stuff we feed and the feeds we stuff our senses with.

From the view at the top of the museum steps, one looks down Benjamin Franklin Parkway, at the other end of which stands Robert Indiana’s sculpture “LOVE” (like the original Rocky, the version of “LOVE” in Philadelphia was created in 1976). While Rocky has spun off innumerable sequels, Indiana’s artwork has been reproduced not only in several sculptures around the world and in variant languages, but on countless postage stamps, keychains, postcards, snow-globes, coffee cups, trinkets, and memes. A piece of pop art, it flattens sculpture into its constituent properties of edge, mass, space, texture, color. Still, it is not quite a mimetic image, but rather an icon, a giant letterpress tile foregrounding in its form the transmission of its content through mass production. The materiality of the sculptural surface issues into typography, symbol. Then again, given that Indiana was a homosexual in the Vietnam era, this seeming abstraction of a hard-edge, block-like l-o-v-e could be read as both a powerful profession of emotion and a declamatory political statement.

Does “LOVE” mean something different when endlessly replicated? A rose is a rose is a rose, and yet eros is not the same by any other name. The first time I saw the sculpture, I wondered why someone would make a big public monument in honor of a postage stamp. Ironically, Indiana embraced his status as a sign painter — unlike Abstract Expressionists, for example, the medium itself was immaterial for him. In this way, perhaps, “LOVE” is meant to be spread rather than put aside, encased, and preserved; Indiana never copyrighted the image, and so it has proliferated freely and boldly in various forms as if less a singular work of art than a prefabricated citation. No counterfeit is possible, no trespass of authenticity; all prior “LOVES” get retrospectively erased in the presence of each new one.

If pop art gets absorbed back into pop culture, does it thereby lose the critical distance to parody or comment on the thing it depicts? When Burger King recently used archival footage of Andy Warhol eating one of its burgers in an ad campaign, for example, did Jorgen Leth’s subversive little film get transformed from performance art to corporate kitsch? Perhaps not. Warhol originally asked for McDonalds, but settled for Burger King over the generic hamburgers offered on set. The Heinz ketchup bottle recalls Warhol’s working-class Pittsburgh roots. Fast food is democratic — though personally I think this idea is a whopper since such franchises create disparity between wage-laborers and their capitalist overlords. Nonetheless, the leveling of cuisine between celebrities and the common man through mass production is celebrated as well in Warhol’s famous iterations of soup labels. He puts the “camp” back in Campbell’s, so to speak, canned as it is.

Warhol got his start in the Mad Men-era of marketing and commercial illustration, after all. He arranged the shop-windows at the Fifth Avenue department store Bonwit-Teller — as did other artworld heavyweights: Salvador Dalí, James Rosenquist, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. Nowadays, many of those same artists have work on display in the executive suites of various corporate headquarters. The moneybags and muckety-mucks walk by these works every day and barely afford them a passing glance. They’re just status symbols, merely wallpaper.

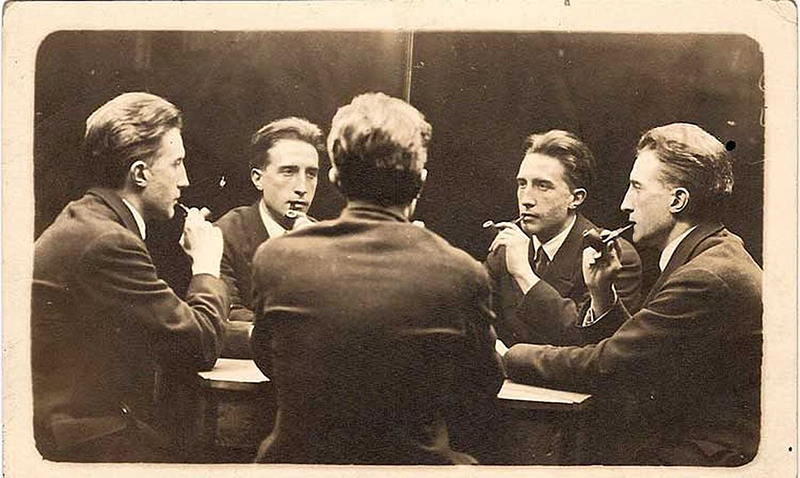

But why does wallpaper have to be banal? The Bauhaus, following the earlier Arts and Crafts Movement, proposed that everyday objects, if they used high-quality materials, were designed with functionality foremost in mind, and were constructed in a spirit of free-thinking intellectual inquiry, could be on a level with the traditional fine arts. Walter Gropius and his confreres at the Bauhaus planned to mass produce chairs and desks, door handles, teakettles, and tableware that had a decidedly revolutionary bent in their utopic project to bring artwork into the realm of quotidian use. Walter Benjamin — who, as a young man, would have been walking around the same Weimar milieu as the artists of the Bauhaus — argues that in our Age of Mechanical Reproduction, we disseminate artworks in many versions, a process hastened from print to film, which “substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence.” The authority, the “aura,” instantiated by the original diminishes; ultimately, for Benjamin, he views the ubiquity of undifferentiated copies leading to “the liquidation of the traditional value” of any “cultural heritage.” Our ability to perceive has been fundamentally altered. The paradigm of art as a sacral, cultic object — passed from deities to priests to laymen in a ritual like the commandments of Moses — has been replaced by the sociopolitical function of a work.

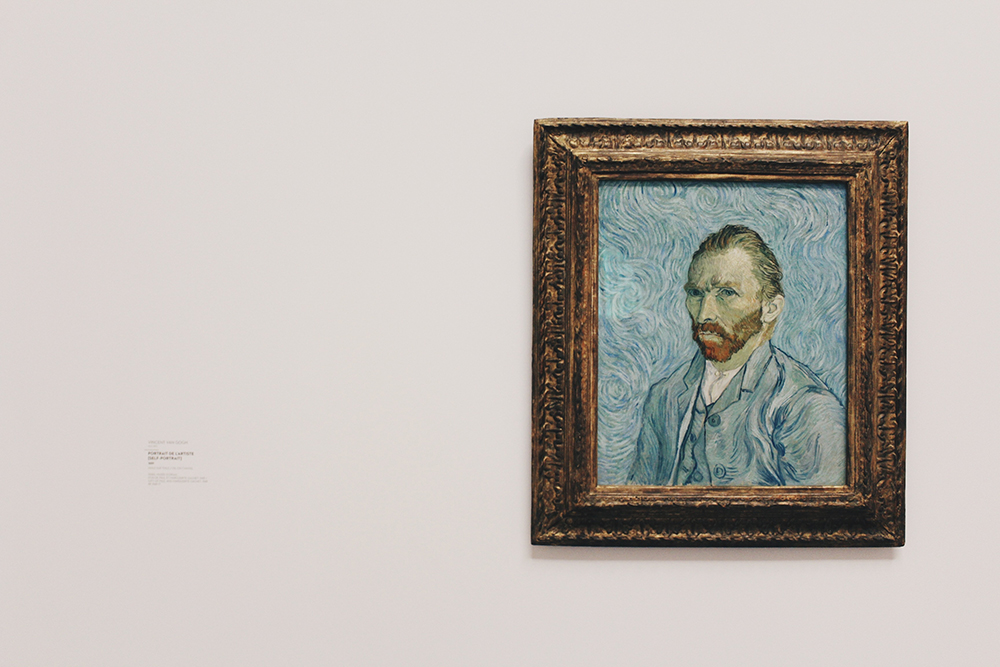

At the Philadelphia Art Museum that long-ago teenage day, I dutifully climbed more steps inside and circulated through the Modern Art wing. I passed by the Ash Can School, Degas’s dancers, Cézanne’s bathers, and the guileless half-alien, half anthropomorphic figures of Klee and Miró. A weekday morning, the galleries stood empty, drafty halls where I could stroll alone like an exiled prince. I turned a corner. I arrived at a bizarre odditorium, a large room with inexplicable gewgaws and gimcracks: the Marcel Duchamp collection. A birdcage full of sugar cubes, a comb, a bicycle wheel, the infamous urinal, “Fountain.” It felt like the inverse of that moment when I stepped out of the MoMA into Midtown, where everyday objects took on a revelatory hypnotic sheen; here, readymades of ordinary items had been placed on pedestals within the museum space.

This curatorial elevation, however, prizes Duchamp’s found pieces as having equal status as the great paintings in their gilt frames displayed in the adjoining galleries. The museum imbues a prestige to these items, asking the viewer to comport their aesthetic gaze toward such mundane bric-a-brac. Duchamp often claimed, however, that he chose these objects for their anesthetic qualities. Duchamp supports the notion that his readymades undermine the artwork’s “aura.” As related by Calvin Tompkins, Duchamp stated:

In art, and only in art, the original work is sold, and it acquires a sort of ‘aura’ that way. But with my readymades a replica will do just as well. I never even showed them until a few years ago, except for one exhibit at the Bourgeois Gallery in New York in 1916. I hung three of them from a coat rack in the entrance, and nobody noticed them — they thought it was just something someone had forgotten to take out. Which pleased me very much.

From this anecdote, he aimed to eliminate the nimbus, the holy air of consecration, which surrounds aesthetic endeavor. If gallery-goers couldn’t recognize art without the pedestal, the monetary aura, or the institutional frame, so much for gallery-goers. So much for art.

Duchamp’s attitude feels radical, even today. It obviates the line taken by Arthur Danto, the influential art critic and aesthetician; Danto insisted that art was distinct from, say, commonplace materials and events due not to its intrinsic formal properties but because of some philosophical context: artwork as such must have a framework, a context, a philosophy. What separates Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, to use Danto’s habitual example, is not the way they look different from actual Brillo Boxes in a supermarket, but rather the methods of looking that the culture of the art-world brings to bear through attention upon the object or event. Finding a trans-historical definition of art nagged at Danto throughout his lifetime, whereas I think the investigations of Duchamp destabilize any universal claims. Duchamp evacuates the artwork of its art-world ostension, of its demarcation of worshipful attentiveness. Art is everywhere; there is no art. If we fail to see, then we have failed to look. If you desire music, then simply listen, as John Cage might urge. Every culture, every person is free to regard art differently. Or to let it go unnoticed.

Duchamp’s original readymades have all since been destroyed, lost, returned to their functionality. The objects in museums are replicas. A question of provenance is thus raised by the fact that the things on display are not technically readymades at all — if by that we mean an object plucked from daily use by the artist — but rather deliberately fashioned reconstructions chosen or created by art restoration workers after Duchamp had been commissioned for duplicates that met his approval. The metaphysical joke of a readymade has been reversed: the things in galleries were never intended for trivial use, contrary to all appearances.

The nom de plume, for instance, on the urinal, “R. Mutt,” indicates Duchamp’s penchant for mongrelization, playing on the “Mutt and Jeff” comic strip, the J. L. Mott manufacturing company, and slangs for the name Richard. Now, however, this signature is no longer necessarily from the artist’s hand. It’s a double forgery. And so, the work has been vacated once again of its ontological oomph. While Duchamp claimed that he chose his readymades for their anesthetic quality, rejecting the whole terms by which the art game was played, almost immediately — when Alfred Stieglitz photographed “Fountain” and recognized the beauty of its virgin- or Buddha-like shape pieces became conscripted into the Modernist discourse of beauty and banality. The bicycle wheel on a stool, the first readymade, Duchamp said he constructed simply because “he liked to look at it,” which belies any anti-art impulse. If the reception of the readymade had transformed everyday life into art, in a spirit later taken up by groups like FLUXUS and the Happenings of the ’70s, Duchamp’s “genuine” replica already consecrated as high art merely imitates a commonplace object, ironically aligning it again with the mimetic tradition of sculpture. These replica readymades have been twice divested of their quiddity — the replicas and originals almost nullify each other’s raison d’être.

We no longer acquire tradition as something uniquely handed on, some residual touch of its supernal origin inhering in the thing transmitted; rather, today in our technocratic, hyper-capitalist global state, taste is an algorithm of consumption patterns with minimal, click-through input from actual consumers. As Benjamin presciently concludes, our reception is “in a state of distraction . . . the public is a critic, but an absent-minded one.” We dance around the golden calf.

However, it might be worth noting that if Warhol had his Factory, so too did Renaissance artists have their workshops, where copies of popular works could be mass produced; going back further, even the tablets of the law arrived secondhand since Moses broke the originals in a pique of rage.

In this light, the “Rocky Statue” created by A. Thomas Schomberg in 1980 as part of the set of Rocky III, currently placed near the front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s main entrance, in point of fact pays tribute to the older, cultic value of art. It signifies that these are the very steps that Stallone skipped up, and which you, too, retrace in your journey to the heights. The antiquated museum design with its Greek columns and frieze encodes the building as a temple, a repository of authenticated objects touched at whatever remove by the old masters. If the Rocky statue strikes one as crass or incongruous, it’s because this most traditional homage — a larger than life bronze statue at the foot of a temple — represents not some marble Apollo, but a champion of the underclass, a matinee idol of popular Hollywood movies, the medium according to Benjamin most responsible for emptying art of its aura. Though Stallone may be real, Rocky is fictional; and yet, the statue collapses this distinction. Visitors can momentarily become Rocky, just as the movie’s fantasy has been corroborated by the solidity of the steps and statue. I, too, confess to once traveling two hours to Philadelphia one bored night in high school just to jog up the museum’s 72 steps.

Even in its traditional affirmation of cultic value, of aura, the campy nature of the statue rubs some people the wrong way. It has been removed twice, and twice moved back onto the museum grounds. Though some have said the statue is merely a movie prop, and therefore undeserving of its prominence in a hallowed sanctum of art, nobody made such claims about, say, Matthew Barney’s display of the mise en scène from his film series The Cremaster Cycle at the Guggenheim. Perhaps what’s most disturbing about the Rocky statue is that it possesses the value of cult films, which knowingly elevate the cornball and abject, not what Benjamin terms the cult value of high art; or perhaps, distressingly, the statue really does sacralize our society’s highest values: the All-American Everyman’s bootstrapping ascent, the Protestant work ethic.

At first skeptical, a tad supercilious, I’ve since developed an appreciation for the statue. Placed in front of the museum, its slight whiff of absurdity maintains a power to defamiliarize one’s conventional, snobbish expectations about art. The “Rocky Statue,” after all, achieves that queasy feeling of dizziness or flummoxing which results from displacement — when meaning pulls apart from context and the old auras hollow out and yet nonetheless find themselves re-inscribed in some new constellation — that many of today’s cutting-edge artworks wish to inspire.

Leaving the museum that day long ago, I gave the Rocky Statue a double-take on my way home. •

Photos by Alina Grubnyak, on Unsplash; Sang-Min Yoon and Todd Von Hoosear, on Flickr; and Coldcreation on Wikimedia Commons. All images are in the public domain.