The last play I saw in person was on the evening of March 12, 2020 — a date that, in retrospect, was close enough to the official start of lockdown in New York City that I can’t help feeling like I’d gotten away with something — a heist, maybe, or narrowly missing a collision with an oncoming vehicle.

It was a rainy evening, and as I ducked into the lobby of the Irish Repertory Theatre in Chelsea, I noticed that the ushers and box office attendant were all wearing latex gloves. Suddenly, I became panicky over protocol. Would I be thrown out for not wearing them? Did carrying hand sanitizer mitigate my offense? Masks at that point were not yet mandated and luckily, the ticket scanner let me in without incident. As I searched for my seat, I got the distinct impression that I had stumbled upon a private viewing: in the dimly lit audience, I counted only a handful of other patrons, seated a discrete distance from one another.

The play I had come to see in the final week of its run was a dramatic-reading-cum-enactment of Paul Muldoon’s “Incantata,” a grief-sodden poem about a husband’s attempt to make art — to reconstitute his world — in the wake of his lover’s death. Perhaps choosing to heighten its kitchen-sink quality, the Irish Repertory Theatre staged the poem as a man (in a superlative performance by Stanley Townsend) speaking to a video camera in a crammed flat, as he laments his late lover while making prints from cut up potatoes dipped in blood-red paint.

By turns elegiac, loquacious, and restrained, Muldoon’s poetry (or should I say Townsend’s performance?) advances more by rhythm than reason, with lines doubling back on themselves and threatening to spill over with a polysemous play of words. Rereading it now, it’s impossible not to be haunted by certain stanzas that cast undulating ripples to our current moment: “I wanted to […] body out your disembodied vox / to let this all-too-cumbersome device / Of a potato-mouth in a potato-face / Speak out, unencumbered, from its long, low, mould-filled box,” says the unnamed speaker, freshly dislocated by sorrow.

The very next day, the theatre announced it would be going dark, in compliance with orders from then-New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

It was with a heavy heart that I made the trip back home to Washington, D.C., where I’ve remained since mid-March. That same week, my workplace announced that employees could begin working remotely. But it was only after a desultory four weeks of denial that I felt the curtains come down on a big part of my life. It was true that I could still turn to books (mercifully, local libraries had decided to forgive fines and extend due dates), TV shows, music, and movies, but it was hard to sit helplessly by and watch as cracks began to appear in the edifice of performing arts.

If humans have in the past been crudely typified as animal laborans and homo faber — mankind as toolmaker and fabricator — the onset of the pandemic might be said to have given rise to a new category: homo computare, man as computing animal. Granted, we still make things; some of us might be using the “extra” time working from home to bake bread, knit, remodel kitchens, grow gardens. But a perhaps even larger segment of the population — and I count my entire household as members — seems to have developed a frightful fluency in R-naughts, serology test results, true infection rates, herd immunity, monoclonal antibodies, convalescent plasma therapy, and all things virology. In this plague year, it’s the same instinct for control — the same impulse to domesticate fear — that leads us to ritually count the accumulation of days, weeks, and months, and calculate the ones still to come. Cue Beckett’s “Endgame,” perhaps the ur-text of the moment: “Grain upon grain, one by one, and one day, suddenly, there’s a heap, a little heap, the impossible heap.” How many grains of sand make a heap? How many moments make an event?

For 230 days straight, I held out on watching theatrical performances or readings online, for all the obvious reasons. Glitching screens. Poor sound quality. Shaky or grainy footage. I had watched a few digital performances pre-pandemic and still had the residual feeling that watching a performance on a small screen sans live audience could only yield a subpar experience. Watching a play on a TV screen is like taking a shower with all your clothes on; you’d still get wet, but it won’t be a fully immersive experience for your epidermis.

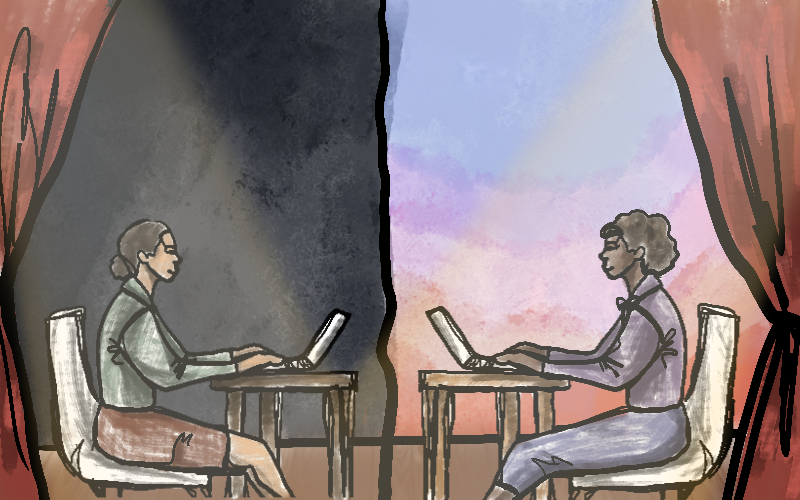

Then, in November, I capitulated. Well, sort of. I took part in an interactive installment of “A Thousand Ways,” which Abigail Browde and Michael Silverstone at 600 Highwaymen dreamed up as “a triptych of encounters between strangers.” For the first of three parts, 600 Highwaymen would pair up two strangers, who’d spend an hour asking each other questions from a script. This would be followed by a meeting across a table with a presumably different stranger, abiding by social distancing rules at all times. Last, all participants would convene and read from a shared script.

A few days before my interview, the box office notified ticket holders that “A Thousand Ways” would have to be truncated: because of new prohibitions on holding group activities in the state of Washington, there would be no parts two or three to follow. A predicament: could a dialogue between two complete, unseen strangers even constitute a play? This exercise seemed to me a dramaturgical variant of the Sorites paradox. Does a play still count as a play if I take away the set designer? How about the lighting designer? Now the music director. Why not also the costume designer? Writer: exeunt.

Play or no play, I was curious to find out what happens with so little scaffolding in place and curiouser to “meet” someone new. At the start of the call, a robotic voice asked one of us to be “A” and another to be “B.” At no point were we asked to divulge our real names. This was for good reason: complete disclosure would have led us to embellish our answers, to put on a “polyester” persona, to quote Muldoon. Being unnamed licensed us to speak more freely.

I learned that the person on the other end of the line was a divorced woman with a background in theatre, now retired and living in New Mexico. The Voice asked all the questions, which was occasionally irksome: I couldn’t ask any follow up questions or be dilatory in giving answers since I would be cut off. Still, the process never felt like an interrogation and the questions even elicited some startlingly intimate answers. We shared regrets, embarrassments, dating histories, indelible childhood memories.

At times, the Voice directed us to rearrange our bodies, move to different rooms, turn off the lights. At one point, we were asked to imagine the other person sitting in a room with us and give a full sartorial description. Directives were crosshatched with the reading aloud of what sounded like fragments of a mildly apocalyptic novel by Cormac McCarthy involving campfires and car crashes. B volunteered to build a fire as I scouted material for a tent.

We were soon at the end of an hour and the Voice instructed us to tell the other person one thing we would remember. “Your phantasmal voice,” I said into the phone. “Your sweet hesitation,” came the reply. And then silence.

As I write this, at the end of 2021, live performances are making a heralded comeback on Broadway. “A Thousand Ways” has recently been revived — this time, to include Part Two: “An Encounter,” in which each participant sits across a table from a stranger, divided only by glass. Relying on no more than a handful of props and index cards, participants are once again prompted to disclose pieces of themselves and co-create a story. Theater, at its best, has always been a conduit for audiences to spiritually commune with actors onstage, to enter a slipstream of time at a shimmering distance from our own. I can’t tell you precisely what “A Thousand Ways” will offer you — each “encounter” emerges from the chrysalis of conversation — but for me, it delivered a jolt of something I thought I had become numbed to: a chance to bear witness to the life and memories of a perfect stranger. •