DD: I thoroughly enjoyed the book, Nathaniel. It was a real pleasure to read and to think about it. There are parts I went back to again and again. It’s a book about history, but it’s not just about history, and at the same time there’s a lot that can be taken out of this to have us think differently about cities. What were you intending to say about Philadelphia?

NP: So, this is my third book about Philadelphia, an interpretation of this city in its contemporary form. And also having written this long history documentary, the amazing thing is having more to say, and that’s been the surprising and wonderful thing. Why is that? In part it’s because of these collaborators.

Peter Woodall is a very sensitive observer who’s experienced Philadelphia from its real nadir starting in the early 1980s and has seen the change and has read deeply about other cities and their qualities. Joseph Elliott came here in the year 2000 with an eye towards a particular material culture of the city and an interest in the visual material. And those two people influenced this book. I mean, of course. We collaborated on it. So, for me, what’s changed about my thinking or what this book has done to help me think about the city in a new way is that I have attached these sort of historical and psychological and cultural things that I’ve always thought about: the ideas of this city intersecting with the physical city.

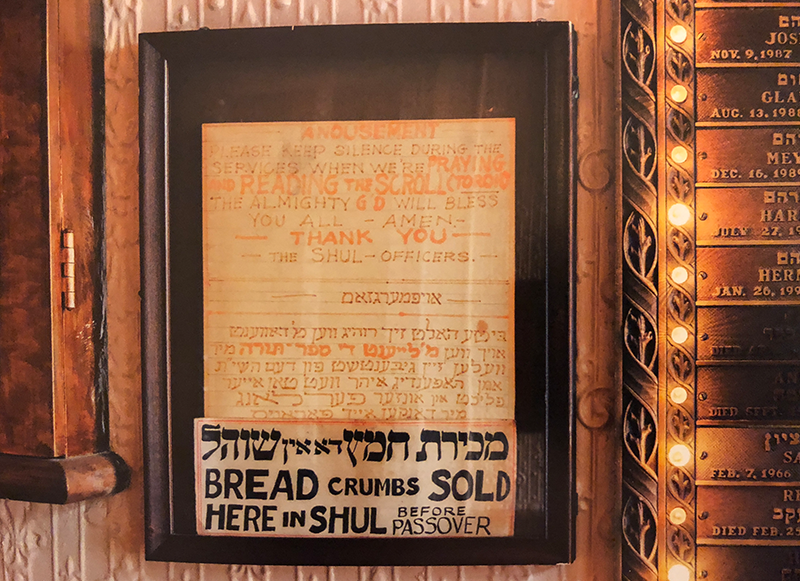

But now I’m really paying more attention to the material palette of Philadelphia and the way it represents and projects its history, its culture, its present, its anxieties, in a particular way. And I look around now, and I’m seeing the city differently, and that’s really exciting. After all these years of study and thinking, here it is alive to me in a new way. Part of that is seeing the work of Frank Taylor in the late 19th century and relating my own visions to what he saw, the way the buildings come together, the way the buildings intersect with the people in an intimate kind of way, and that material form-building and building through its layers.

DD: That’s one of the really unique observations that you all make in the book: Philadelphia never going through a catastrophic period of redevelopment. You give comparisons to other cities, but by not going through that, it allowed us to keep some of this material culture and institutions and the feel of the city that’s unique. It seems like you’re really striving to refine the thinking around Philadelphia’s identity.

NP: That’s exactly it. Philadelphia was extraordinarily relevant to the American narrative until about 1925, when it’s fallen off. And it has maintained, it’s committed, it’s ambitious. It never lost those original founding things that drive to improve life on earth for human beings, which is really part of the DNA of Philadelphia, all the way from the beginning. It never lost those things.

But in this book, we take it upon ourselves to refine our thinking about what makes this city in its particularity worth thinking about and not always be right in the way we conceptualize things because we’re taking some leaps in our urban theory, and we’re applying some ideas, and we’re trying to make them work, and we’re attaching them to a photographic narrative as well.

It might not always be right, but it’s incredibly important to be able to think about this city clearly as it is while at the same time understanding that, of course, it’s part of a larger narrative. It’s not that different from other cities. In fact, many cities going west across the US are deeply connected to Philadelphia’s development, even repeated our grid and street names and all those kinds of things in part because of the railroad.

But when we think of Philadelphia and its particularity, one thing that we realize is that Philadelphia was rich enough in the 19th century, one of the richest places on earth. So it created all this stuff. All this gilded age stuff. We think about Philadelphia as a colonial city, but that’s a false idea. The Philadelphia that we live in is really mostly built in the 19th century. It was rich enough to build all of that stuff and poor enough in the 20th century not to wipe it out. That’s the nut that makes Philadelphia particular. At a theory level, it means Philadelphia in the present — and this book is about Philadelphia in the present — it means that this book is a book about the city in the present. It’s not a history book. It uses history. So the present is always in tension with that past, which weighs heavily on us. We think about it a lot because so much of it is present in front of us, and so much of it is important to American history and American life. And then this future, which is always a kind of maybe. A kind of aspirational future, never a certain future, at least since 1925.

That tension is a particular quality for Philadelphia that makes it different from other places. Part of the reason that so much of it is left to us is that we did not have catastrophic change, and that’s something we talk about in this book. The layers of this city build up over time. We think about this city as a collection of layers, but it is important also to remember that we had one of the most rigorous urban renewal programs. It was a model. That’s why Ed Bacon was on the cover of Time magazine in 1964 — because Philadelphia was doing more and more creatively at the time, more innovatively than other cities, never mind Robert Moses and New York. The city didn’t lose its ambition in the 1950s and 1960s; it really was a victim of consequences of being such a powerful and industrial city.

DD: One of my favorite stories, just a quick aside about Edmund Bacon, is when Jane Jacobs met him. She had been a writer, as you know. She was doing a story on Philadelphia, and he showed her one of the projects, and he was flanked by a half dozen of his team, and very proud of his project, and she stood there and looked around and said, “But where are all the people?”

Just totally different visions of the city.

NP: And yet she did endorse his plan for Society Hill because it wasn’t wholesale demolition: It was sensitive, and she appreciated that.

DD: I want talk about this idea of exploration that comes out again and again. It’s not only explicit, but it’s just inherent with this idea of the ‘hidden city.’ To begin with, the book feels like a tour. It feels like I’m sort of walking through it and my mind recreating these places and trying to place them in the contemporary city and understand how the pieces fit together.

It has such wonderful examples of different aspects of the city, whether it be religious or civic institutions or an industrial site, both layers as well as repurposed, reused. I imagine it must have just been at one point difficult.

NP: We really fought with this book for a long time, exactly. We could not properly conceive of it. And we had Joe’s photographs, that he had said, “Okay, I want to make a book with all this material that I have,” and then we had our own ideas and our own interests and our own thoughts about what kind of book was really needed and also what kind of book we’d be interested in writing.

Pete and I have been going through that process and thinking about the city and trying to figure out what is important that we say. Then we went to Rem Koolhaas’s manifesto about New York, which was that a city, there is no other city, a city develops by catastrophic change. It develops by wild ideas. It develops by extraordinary people’s visions. Not sensitive visions like John Fry’s, but Coney Island visions. That’s how cities develop.

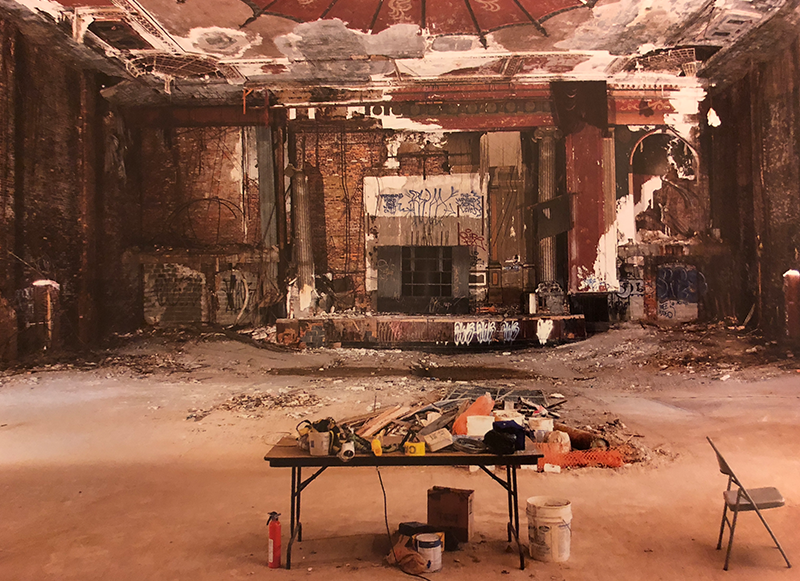

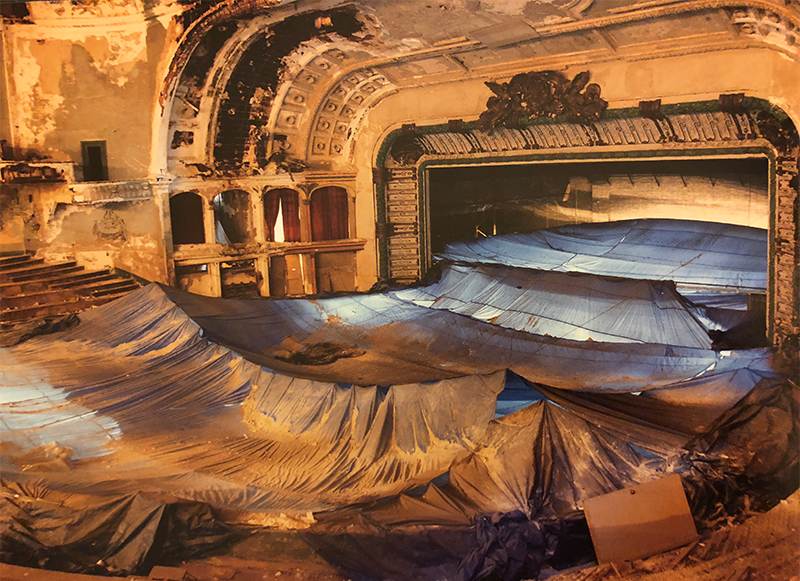

And we said to ourselves, ‘Well, we have some of that. We’ve had some of that. There is a little bit of that quality in Philadelphia.’ The Metropolitan Opera House, which we do talk about in our book, was that kind of impossible building. It was only open for a few years. Oscar Hammerstein, Sr., conceived it and didn’t think it through and there was a 10,000-seat opera house without enough clientele. We thought that Philadelphia really developed at a very different model than what Rem Koolhaus was talking about, so that really set us off to think about ‘Okay, how do we conceive of the Philadelphia model of urban development, which is not catastrophic but accretive?’ And once we had the accretive idea, then we could start to see the layers. We could look at a place like the Church of the Advocate and identify that this isn’t just a church that was built to look like a French cathedral from the 14th or 15th century. It wasn’t just a church where the first Episcopal female priest was ordained. It wasn’t just the church where black power meetings happened in the 1960s. It was all of those things and we can see them all.

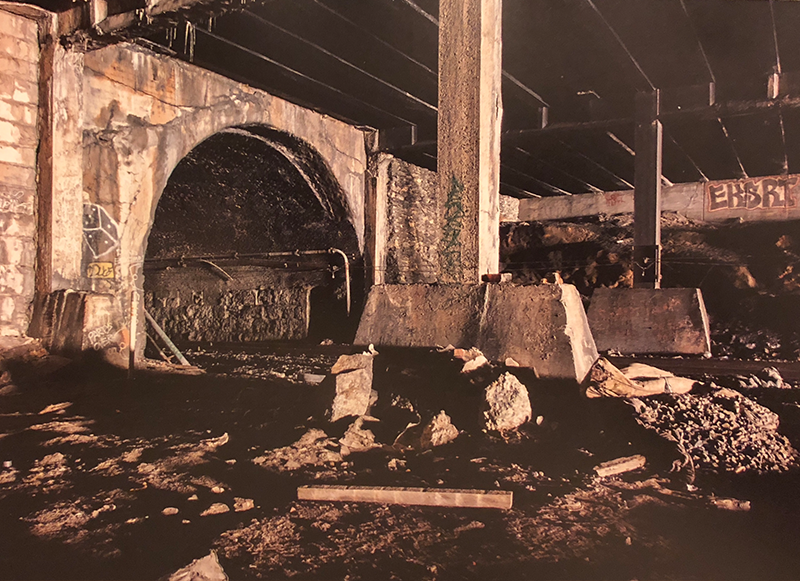

That helped us. So, then we really understood. Then we also understood that places. That there is this notion of ruins, and we talked about urban exploration. In the, I would say last 15 years, the urban exploration concept has been Shanghaied a bit by those in love with ruin porn . . .

DD: I underlined and circled that phrase.

NP:. . . People who love to go inside of decadent places that are beautiful in their decadence. This is why Detroit is so evocative to people, and there [are] great photographers and urban thinkers who have approached Detroit, and Camden, and sometimes Philadelphia. And people from all over the world have come to Philadelphia to shoot Holmesburg Prison or Eastern State. But, ruins really have a different quality because all throughout history ruins have been the raw material for reuse.

DD: There’s this one part I wanted to read. I just loved it:

You say, ‘And so we begin to seek out ruins, not as evidence of decay, but rather as raw material for our imaginative lives. Locating ruins, getting inside them, uncovering their history taught us to read the city as ruins became part of our understanding of the life cycle of urban places.’ You also make the distinction between vacant and abandoned and this ruin porn but sort of exploring places in their authentic sense.

NP: And this is where it’s exciting for me because a long time ago when I wrote Song of the City, I divided the book up into body, something, soul, and seed. And so I was thinking already then about the lifecycle of cities and the way they regenerate. There’s so much regenerative energy in a city that it does remake itself. Now that concept gets attached for me in my understanding of the place, much more clearly through material culture.

I’ve never been one of those urban explorers who breaks into buildings, but Pete has been for years, and Joe has been going inside these places to photograph them. Working with both of them has helped me to sort of apply that concept more specifically and to see it — really, to understand. One of the greatest things I think we’ve done with the Hidden City Daily is all of those articles that tell the story of one building, and it’s not a singular story, it’s stories layered on top of each other.

Somebody builds it for one idea, somebody takes it over for another idea, and you get from here to here, very different places, and each of those people are adapting that building and making it different. To me that’s what preservation is and it’s also what makes the city special.

Getting inside of that process for me — it’s evocative of life and it inspires me.

DD: You know, you also talk about seeing the city as almost there are shadows of its former self, like a faded mural or an advertisement on the side of a building. A marble sign that speaks to a previous time or something like that.

One of the things I love about Philadelphia, and you all nailed it, is it’s a kind of a city that you need to spend time with and also you need to look up and look around because that’s where you see those things. That’s where you get a sense. It’s the buildings that you talk about, it’s institutions, but it’s also just about the ordinary.

NP: It’s that ordinary thing, and what it does — I think — is it expands your now; it expands your present to include the past. And so now you’re not only living today, you’re walking down a street in the present-day city, but you’re looking up and you see a sign on ninth Street, between Bainbridge and South, there was Via Bicycles. You remember Via Bicycles, don’t you?

DD: Yeah, yeah.

NP: They moved, and somebody has bought the building. They pulled down the sign, and it says “Tripoli Barber Supply.” And now — and then we did a story on that and it turns out it was I think it was either a numbers-running place or a — what do you call it, during Prohibition?

DD: Oh, like a speakeasy?

NP: Speakeasy or a distillery.

DD: Yeah, okay.

NP: I forget which, but there’s a secret history. Tripoli Barber Supply. Barber supply? Why is there a barber supply? Well, okay, that makes sense. Tripoli must have been Italian. It has a kind of classical Italian façade.

That’s the layers, but it expands on what it means to live in the present day. And then you’re dreaming about those people’s dreams. Like somebody came here as an immigrant and conceived of this as a place to make his life.

DD: How do you see the future of Philadelphia? Where are the decision points now? What do you think we’re facing as a city? I don’t expect you to have a crystal ball, but, you know, you’ve thought about it.

NP: I certainly don’t have a crystal ball. I would a say a couple things. One is it’s such a vast world and all American cities are getting their asses handed to them, particularly by the cities of Asia. We had our Industrial Revolution and they’re having theirs, in a certain way. But even a place like Seoul or a place like Saigon — they’re conceiving of urban life in ways that we’re not going to. The scale, the amount of stuff, like cultural stuff too — museums. And the built form; it starts at a different place. I think we’re already struggling with that a little bit in terms of American cities.

And then I would say the second thing that I worry about is there’s no infrastructure spending, so we can’t be building the subway systems that every American city should be building. We’re going to fall behind. Then the other part of that is that we’re very, very worried about a city like Philadelphia — if you close the borders, which is what is happening right now, the borders are being closed, and you’re kicking out people, you’re literally deporting them, that is very dangerous for American cities who have always grown on immigration. Some of it is domestic migration, you know like the Great Migrations, but that ain’t happening anymore.

DD: Sure, even regions of the city. Look at South Philadelphia, right? I mean look at Saint Rita’s Church on South Broad Street, which is the epicenter of the Mexican, Mexican-American, Latin-American population in South Philadelphia.

NP: This is what cities do. They absorb people. People get themselves, find their way, and they either leave or whatever happens, but that’s what cities do. If you cut off immigration, then this is why it’s a question of survival. This is why the rhetoric that comes out of the mouth of Mayor Kenney and other mayors is very, very severe, ’cause usually you would have some deference towards the president, but this is survival. Every single thing that this administration has tried to do could be fatal, and I worry about that. Institutions also live and die on people from abroad. So that worries me, and we’ll see how that goes.

I’ll go out and say it: If something like Amazon were to come to Philadelphia, it would be a good thing because Philadelphia has set itself back on a course on its own two fricking feet. It has figured it out on its own — with certainly a lot of help from the federal government, some help from the state government — but really there’s not a lot of real powerful outside forces playing in on this city.

Los Angeles is the beneficiary of a lot of outside forces. New York is a beneficiary of a lot of outside forces, ’cause they’re so attractive.

Being able to be attractive is maybe a bit of the difference in terms of what could happen next. That’s important. Cities have been fetishized now. Cities are popular. The cultural gestalt of America is not Orange County, California; it’s Brooklyn, New York. And it is still that way even into the Trump administration, but that might not last. It’s hard to say. We need to keep immigrants coming, and for Philadelphia, we need to be able to attract and eventually, build up. Maybe we are attractive now. I think the institutions are attractive. Are they enough? We’ll see.

DD: Well, we still have some chronic issues, right? I mean, you mentioned infrastructure, transportation, the story of the sesquicentennial and the loss of revenue from that prevented any future plans besides the Broad Street Line, and here we are in the 21st century really dealing with that thing, and that shapes the future.

NP: All these things, too. So we are in fact shaped by the past, and some things may not be escapable. On the other hand, you and I, had we been in 2001 thinking about, “Well, we like this city, we thought it was great and we’re interested in it and interested in studying it,” would we have imagined that it would begin to dazzle people once again? I don’t think so.

DD: I don’t think so, no. I’m continually amazed at that with students, for example. 19-, 20-year-olds, just their view on cities, in general, and Philadelphia.

NP: It excites them.

DD: Yeah. It also brings up this question of authenticity. Which city are we talking about, right?

NP: One of the greatest things, I think, that has happened in the last few years particularly is the way that the power structure has opened itself up, not to more African American representation, ’cause that was long ago, and particular African Americans are very well integrated into the power structure of Philadelphia and have been for a long time. But at a cultural and economic and also political level, partly because of #MeToo, partly because of the failure of the election and the resistance that’s building, there are amazing people, advocates, poets. I’m thinking of the Philadelphia Assembled Exhibit at the Museum of Art that is closed now, but here was this old-line institution inviting all these voices in not only to say what they want to say, but to make sense of and document their own history and build on that for something more going into the future.

And so, I do think that this is an awfully inclusive place. It’s more inclusive now than it was, for its utter benefit. Well? There it is.

DD: There it is. •

All images courtesy of Joseph E.B. Elliott. Featured image collage and manipulation by Isabella Akhtarshenas.