Last Halloween, my husband opened our closet door and reached for the topmost shelf where he keeps his Zipperhead mask.

“Not again,” I said.

He ignored me as he is often wont to do and pulled it on over his face.

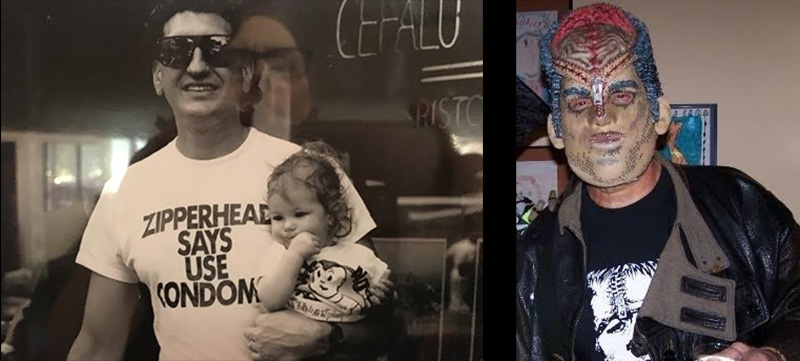

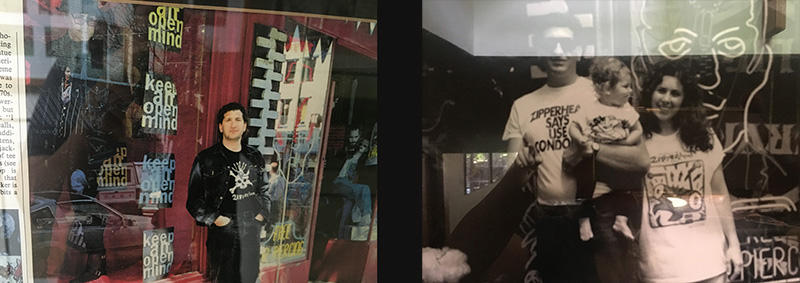

My husband had worn this mask all through the 90s and now, in 2015, looked forward to going out in public in it that very evening. The rubbery skin covered my husband’s face. A half-opened zipper to match the one painted on the store’s façade next to the gigantic metal ants, stitched through the mask’s forehead and nested in the mask’s crown of red, kidney-shaped brains. He opened a flap and beneath it found two switches. He flicked them on and the exposed brain particle lit up with tiny dancing lights. My husband also dug out his black Dr. Martens and a Zipperhead T-shirt. Punk is long dead. My husband sold Zipperhead in 2000 to Rob and Steph, his two top employees who were married to each other. They ran it as Zipperhead for several years, then relocated it around the corner in a smaller space, and renamed it with a touch of levity Crash Bang Boom.

I remember the jars of Manic Panic laid out on the counter, that hair dye that you could mix in a bowl and apply it to your hair to turn it pink or green. After coming face-to-face with the plaster of Paris Elvis bust, you stood mesmerized beneath T-shirts that hung from the hot pink walls. The racks were with filled with clothes you’d seen on MTV: studded jeans in black overdye, zippered shirts, vinyl skirts, and dresses held together with safety pins. But walking into Zipperhead really came at you when your eyes focused on the aquarium on the counter. In it lay a tarantula covered in leaves. (There were actually two of them, but the first one ate the second one alive.) You could only see the remaining one if you rapped the glass and got it to move, but there was a sign posted asking you not to do that. I’d peered in more than once to catch the sight of a hairy tentacle waving in the air, summoning me.

Besides the tarantula and the Manic Panic, the counter was stacked with hundreds of pins with the names of punk rock bands written on them — PIL, The Clash, The Specials, BuzzCocks, Dead Kennedys, Blondie. Inside the glass case you could find skull rings, handcuffs, earrings, black leather whips, shot glasses, mugs with skulls and crossbones painted on them, spiked arm bands, bandanas, and best of all, Bayoun greeted you from behind it.

Bayoun, his jet black shoulder-length hair and dark eyes. He wore a flannel shirt over a tight T-shirt that showed his ribs, a wide leather belt looped through his faded jeans. Because I was the owner’s wife, he lavished attention on me. If he was opening a dressing room door for a girl in Docs and a pink Mohawk, a girl half my age, he’d leave her side and assist me. Though rumor had it, he and the other salespeople didn’t really like when I came into the store and tried on clothes that they weren’t going to get paid a commission for.

I didn’t care. I may not have been one of them — I missed being part of the punk scene because from 1979 – 1983, I’d been living in Iowa City where I attended graduate school and still shopped in India import stores and dressed like a hippie — but like them I cultivated an attitude. I remember how the store’s employees eyed me suspiciously when they first met me at a party in the backyard of the store. Actually, the first time they saw me, was through the lit up second-story window where I’d been standing on the toilet to see myself in the tiny mirror over the sink. I’d grabbed a pair of tights, Docs, and a pre-shrunk sleeveless black T-shirt from the store. It took effort to dress for that party. I wanted to earn the respect of girls like like Zip Gal Val, who worked in the store, and was an exact bookend for Bayoun: short denim cut-offs, tiny T-shirts and scarves printed with skulls on them, jet black hair, brown eyes, and pallid skin. I idolized her and the store’s manager, Margarita Passion, who came to Philly from Canada when she followed a guy in a band, and in her strawberry blonde mullet and tight black clothes she looked like Patti Smith. The things she said were so cool that just to hear her speak was like listening to a spoken word soundtrack. Unlike me, she didn’t need to go to school to learn how to make art. She was an artist of life.

The day Courtney Love came to Philly and walked around South Street, she visited Zipperhead. When Love saw a T-shirt with the words RIP Kurt Cobain and a copy of his death certificate printed across it, hanging on the wall, she knocked some garments off the counter not too far from where the aquarium with the tarantula stood and reached across with her cigarette lighter to set the T-shirts on fire. People heard about that moment on radio shows all over the country, some critical of Love but most completely blaming Zipperhead for selling unauthorized shirts with Cobain’s death certificate on them. Either way, the incident aided Zipperhead’s outrageous image.

The roots of Zipperhead’s bad attitude went much deeper than punk culture. People don’t realize this, but many of the store’s signposts, such as the plaster Elvis bust that stood in the doorway was one of many that my husband’s father sold when he owned Millan’s Hardware at 4th and Bainbridge Streets. It was the kind of hardware store where you would go in search of a specific nail or screw and my husband’s father would lead you to the back or down a side aisle and begrudgingly pick through an assortment of small cardboard boxes filled with screws to locate it for you, even if it took an hour. Zipperhead wasn’t created out of nowhere. It’s jumbled, anti-establishment character had its source in the depression-era experience of my husband’s father, a first generation American whose parents had fled pograms in Eastern Europe, rode cargo class to Ellis Island, and resettled in South Philadelphia.

The City of Philadelphia forced my husband’s father to change the location of his store when it built Southwark, three towering low-income housing projects, now imploded. Once Millan’s Hardware changed locations, it lost its client base, and my husband’s father reacted by rebelling against outward success, such as selling the family car. Even though my husband was ashamed his family no longer owned a car, he was learning an attitude. When Zipperhead came into being, it was more than a retail clothing store, it was the symbol of a state of mind, one that encapsulated rage and pain.

As a boy my husband called himself King Swat. There was a fruit store next to his father’s hardware store and it was my husband’s job to keep flies away. Bored, he retreated to a fantasy world where he reinvented himself as a superhero fly swatter. I didn’t know him back them, but I knew him him in high school. He was the kind of dreamy, adventurous guy who was always seeking out new things, like sky diving, group psychotherapy and camping trips to a secluded campground on top of a mountain called Sunfish Pond.

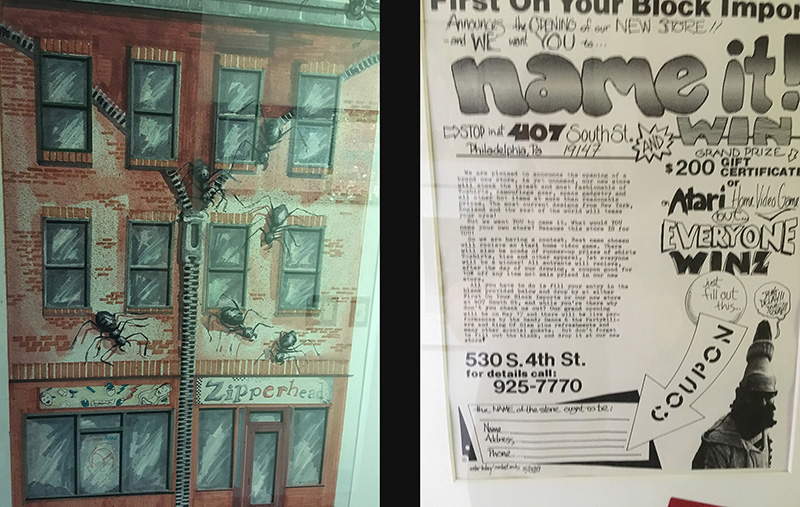

In 1976 he traveled to Guatemala and brought back some patchwork skirts that our friends loved and thus began an import business called First On Your Block Imports with his two best friends, Evan Hartman and Stu Noble. Before they rented a storefront on South Street, they sold their wares on tables at flea markets and outside the student unions of colleges up and down the East Coast. The story of how Zipperhead came into being gets retold with regularity among the members of our family. My husband had rented a space on South Street around the corner from First on Your Block to open a coffee house with his girlfriend where they lived together upstairs. The Phillies had just won the World Series. He came home drunk in the wee hours, got into a fight with his girlfriend, and just to spite her, packed his backpack, went to the airport and flew stand by to London. From London, he visited Amsterdam. The year was 1980. Punk was everywhere in Europe. His eyes opened. He came back to Philadelphia and transformed the presumptive coffee house into a London styled punk rock store — one of the first of its kind in the U.S.

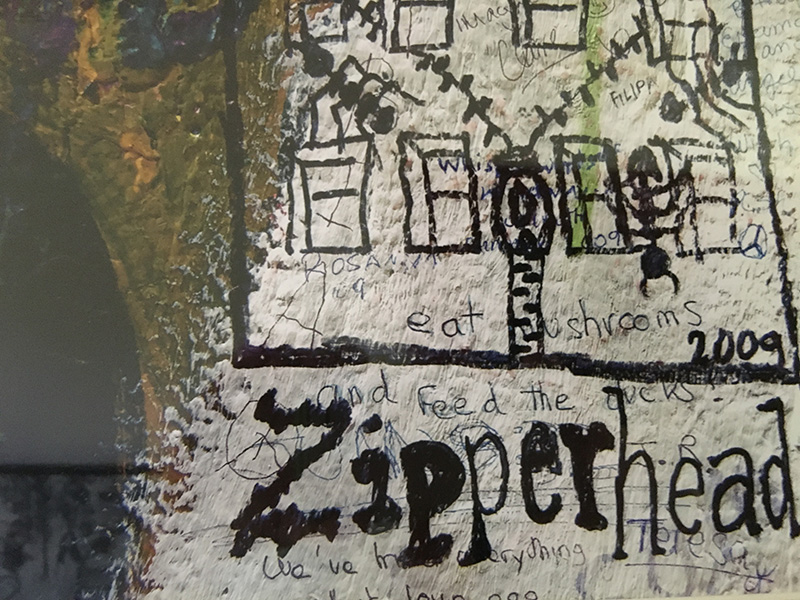

The store got its name in a name this store contest. Raymond Ercoli, an art student at Glassboro State, had just watched the film Eraserhead at TLA when he walked by the store and noticed the mannequins wearing garments with the kind of giant zippers on them that were popular at that time, and came up with the name Zipperhead. His prize for winning the contest was an Atari (Atari was still considered exotic) and he was contracted to design the store’s logo, the very same that featured the Zipperhead character with his brains exposed.

To understand punk’s impact and the appeal of a punk rock retail store like Zipperhead, you’d have to know what it was like to be alive in the 60s and 70s when kids believed that the purity of their messages for peace and love was real. And then when they found out that it wasn’t. That rage led to another counter culture, this one angrier, the music raunchy and raw, the lyrics completely nihilistic. “Twenty, twenty twenty four hours to go/I want to be sedated/Nothing to do, nowhere to go/I want to be sedated,” sang the Ramones. Punk rock existed before the internet, in a time before today’s inescapable consumerism. Punks would never wear T-shirts that advertised corporate owned clothing brands or even social action campaigns like kids do today. It was before the proliferation of remote controllers. When a commercial came on, instead of switching the channel, you’d leave the room. MTV had just launched on something entirely new: a cable station. Parents tried to stop their kids from watching it. On MTV kids could see bands and copy their dress. Zipperhead was one of the first stores to make those fashions available. Quoted in a 1998 Philadelphia Business Journal, written after he sold Zipperhead, my husband called this fashion, “rock ‘n roll to wear.”

The word punk was an English word first recorded in the 1590s. In Shakespeare’s time, punk meant prostitute, which evolved to mean a young hoodlum or worthless person. Both music critic Dave Marsh who wrote for Creem and Legs McNeill who wrote for Spin are attributed with coining the word punk. The just cancelled HBO series, VINYL was edging toward the moment when Richie Finestra feels the vibrations of early punk’s new sound. He’s at a concert where he hears music so life-affirming in its denunciation of everything sacred that his head spins. The music touches him in such elemental ways that he stays up all night snorting cocaine.

Contrary to popular opinion, Zipperhead sold no drug paraphernalia. It was completely free of rolling papers and pipes. Nevertheless, many people who probably never even ventured inside, obsessed about the store’s connection to drugs. Suspicion is natural to people, my parents among them. My mother’s refrain, shouted to me when I met friends downtown, was to “stay away from Zipperhead.”

If other punk retail stores opened in Philly, none of them were as iconoclastic as Zipperhead. Even now when I meet people who discover that my husband started the store, I watch expressions of yearning wash over their faces as they tell me that Zipperhead marked the most important time in their lives or they attribute the clothes they bought at Zipperhead to how they finally decided to drop out of college or travel the world despite their parents lack of support. “One Saturday I took a walk to Zipperhead/I met a girl there/and she almost knocked me dead,” The Dead Milkman, a local Philly band, sang on their 1988 album Beelzebubba and rose to international fame. The video filmed inside the store appeared on MTV, bringing Zipperhead to the national consciousness.

A typical day began with the screech of the metal gate that protected the store’s front windows as sales assistant, Zip Gal Val raised it and revealed the display. Usually some strung out kids would be hanging around outside, kids who’d stayed up listening to bands the night before at TLA or Dobbs. Maybe they were kids like Dave who drove down from New York astounded that he could find a replica of New York’s punk scene scattered on South Street’s pavements. “We’d cruise looking for ladies. It was great. It felt alive.” Maybe they’d crashed at someone’s apartment on South Street and spent the last hour waiting for the store to open, staring at the mannequins through the grating, ready to seize the same black plastic skirt or safety-pinned jeans once they got inside.

When our children were born, my husband sold infant and child size Zipperhead T-shirts and motorcycle jackets. Both my kids wore them: a sign of the next generation’s counter culture. I was not above putting hair gel in my two-year old son’s hair to give it a spiked effect. We lived a just a few blocks from the store. Zapped up on some sugary treat we’d bought them on South Street and dressed in those T-shirts and jackets, our kids would stand in those windows and pretend they were live mannequins. Two decades later, my husband would bring me to Hungry Pigeon, a hipster restaurant off of South Street, that, true to its name, serves pigeon. Not the “flying rats” on city streets but birds raised on farms. He has the openness of mind that led, back when he owned Zipperhead, to his willingness to try out Gyro Advertising when Gyro approached him with their “Keep an Open Mind Campaign.”

Gyro, now an award winning advertising agency was just starting out and wanted to gain notoriety from working with Philly’s flagship store. The ad campaign featured posters that showed a picture of psychopath Charles Manson and the words, “Everyone has the occasional urge to go wild and do something completely outrageous,” and another one of Jeffrey Dahmer that said “Go a little insane now, not a lot insane later.” Beneath those words was the slogan, ‘Zipperhead, Extreme Clothes for Extreme Times.’ The posters were plastered on telephone poles and bulletin boards at Temple and Penn’s campuses and on vacant store fronts all over the city. The next day, the outcry was dramatic. There were multiple talk shows, newscasts, radio programs, and newspaper articles discussing how tasteless the ads were. “At the end of the day,” my husband told me, “what a lot of people remembered was, ‘Zipperhead that crazy store.’ It reinforced our image as an outrageous in-your-face store that stopped at nothing to get people’s attention.” He even ran an ad on cable TV showing a 500-pound woman jumping up and down on a trampoline in slow motion with the same byline, ‘Extreme Clothes for Extreme Times.’ However, he attributes his decision to stop the campaign to his getting a call from a family member of a Dahmer victim. The New York Times reported that the husband/wife team of Gyro said that “the reaction to the campaign persuaded them to put it on hold..

Just this month, two novels have appeared based on the Manson murders (Emma Cline’s The Girls and Caroline Leavitt’s Cruel Beautiful World). I wonder if those authors had a particular message in mind. Cline, who wrote The Girls when she was 25, received a two million dollar advance. Americans, apparently, are still fascinated with the Manson family story.

In 1969, I was 14 years old, the same age as Cline’s protagonist Evie. A teenybopper who rode the subway to a store downtown called Samson Village where I bought my first pair of bell-bottom jeans. Later, my best friend joined MOVE, the Black power, back to earth movement, and lived with John Africa and his family in their compound on Osage Avenue that Philadelphia’s Mayor W. Wilson Goode razed to the ground, resulting in the deaths of 11 members including five children. My friend survived.

“You’re only as good as your last season,” my husband used to say regarding Zipperhead’s sales record. At 6 feet 3 inches, Zipperhead’s iconic defiance still animates him, yet with an air of charm and elan. When we walked into that Halloween party last year, more than one person stopped to take our picture. Others came up and surrounded us as if they were about to throw us off the stage and into a mosh pit. “Zipperhead,” more than one of them said. “That store represents the pinnacle of my life.” •

Featured image courtesy of ancient history via Flickr (Creative Commons).