Ask someone who doesn’t normally listen to classical music to name a work from the genre, and it’s a reasonable bet they’ll cite Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. They’re apt to even hum a few bars of the “Ode to Joy” passage — a veritable vocal wellspring of the human spirit — and there’s a decent chance they’ve heard it performed live at some point. After all, few symphonies are aired more frequently than Beethoven’s last.

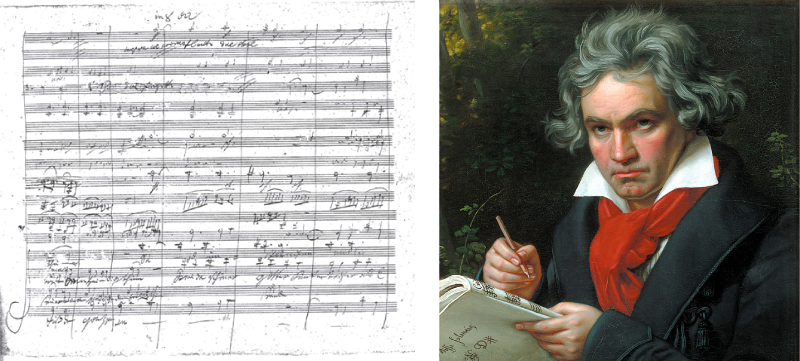

Commissioned by the Philharmonic Society of London in 1817, Beethoven wouldn’t really get cranking on the score until the fall of 1822, having other Beethovian things to do. He’d work off and on until the winter of 1824, cobbling together bits and pieces of other works to make this one: not unlike, say, the Beatles with their long medley on Abbey Road, only blown up to symphonic proportions.

Normally, Beethoven liked to have his works premiered in Vienna, but by the time the Ninth was ready for its first public airing, he had turned on the city, thinking it found too much favor with the rococo prettiness of Italian composers like Rossini. Beethoven was tuneful, and he could move you in the very deepest corridors of your being — he could even set you dancing — but Beethoven was never much into prettiness. Beethoven wanted to premiere the work in Berlin; the music crowd of Vienna was hurt and fretful they would no longer be in favor with the maestro — not knowing, of course, that there would be no more symphonies from him — and so had a lot of patrons, composers, and performers sign a petition, wooing Beethoven back into the Viennese fold.

Unable to conduct, due to his hearing loss, Beethoven sat on the edge of Theater am Kärntnertor’s stage in Vienna on May 7, 1824, gesturing for the tempos. The sheer wall of sound must have been impressive; this was certainly a larger group of musicians than Beethoven had ever worked with, and Beethoven was always a volume merchant, right down to his piano sonatas. Weirdly enough, even at low volume Beethoven just always managed to make sound feel big. The crowd burst into applause, Beethoven had no clue what was going on, and someone turned him around, and there it was: rapture.

Some works leave the repertory, never to come back, and some leave only to return with greater vigor. The Ninth has always had remarkable staying power, save in one instance, perhaps, with someone who might have been its finest interpreter, in Wilhelm Furtwangler.

Beethoven was one stormy petrel of a man. So, too, was another German, Wilhelm Furtwangler, born roughly 60 years after the Ninth’s premiere. This meant that Furtwangler worked through two World Wars, the second of which made it a bad time to stump for much of anything Germanic for a spell. Call it collateral damage. It wasn’t really anybody’s fault the Ninth took something of a hit — after all, of its many associations, one is German nationalism — and you need not have been a master prognosticator to have expected Germany’s prestigious Bayreuth Festival to incur some blows, as well.

The Bayreuth Festival, which opened in 1876, was a sort of Disneyland for Richard Wagner fans. His operas were performed there in all of their Plutonian power, epic lengths, shady ethics, and undeniable majesty. They tended to be performed in Bayreuth better than anywhere else. Things, as things tend to do, took a snag with the Nazis. Richard’s daughter-in-law Winifred Wagner — who married his composer son, Siegfried — ran Bayreuth, and became friends with Hitler. The Nazis took over, abandoned the sets used for Wagner’s opera, angering Wagner’s family — who showed some courage in voicing their ire — and ironically, doing what Nazis hated to do: opening up possibilities for bold, fresh performances down the line. Even, you might say, courtesy of our man Herr Furtwangler, interpretations of older works that border on the Modernistic.

The war happened, out went the Nazis, and despite the bulk of Bayreuth itself being bombed, the theater remained intact. The occupying American forces used it for decidedly American morale-boosting — for it served as a haven for recovering soldiers — fare, what we might think of as light entertainment: comedies, dance hall routines, even circus shenanigans.

The city of Bayreuth was given its theater back in 1946, but the Wagner component didn’t resume until 1951. But what’s interesting is that when it was time for serious musical business again on July 29, it was Beethoven’s Ninth, with Furtwangler doing the conducting, that ushered in the new era, while summing up those of the past, and serving as a challenge to those to follow: a sort of a “follow this” moment that was part directive, part unanswerable command. Because you don’t really follow music like this: You simply try to carve out space for your own from its mighty shadow. Shadow, in the case of this newly reissued recording, which has an awful lot of sunshine in it, intriguingly enough.

Toscanini was the conductor who took Beethoven tempi at a greater gallop than anyone else. It was like he had somewhere to be. Maybe a cartoon-scoring session, for all of his break-neck careening, which he somehow made work, even if Beethoven himself would have been pitching his latest fit. Beethoven did love his fits. But if Beethoven rematerialized as a draconian German in the summer of 1951, he might as well have been Wilhelm Furtwangler.

We tend not to think of a work of classical music as viscerally intense. Emotionally intense, of course, but not a manner of work that riles people up — in a good way — and charges an atmosphere, gives the concert venue the feel of a hockey rink at playoff time. Karl Bohm’s Tristan und Isolde from Bayreuth in 1966 is a bit like this, but this Furtwangler rendition of the Ninth is as viscerally intense as 20th-century classical recordings get. It is simultaneously draining, in what it pulls from you emotionally, and is emboldeningly triumphal.

Furtwangler can go fast when necessary, but unlike Toscanini, he is always incising; his Beethoven never fails to cut deep grooves, like these sonics at hand are etching grooves into the earth as we hear them. There is a delicacy to this situation. Would you, for instance, envy someone jump-starting a very Germanic festival just six years after the war? A festival heavy on the controversial works of Richard Wagner? Richard Wagner was the H.P. Lovecraft of his time, in some ways: a genius who troubled some people because of what they came to learn he either in part stood for, or didn’t stand against, or a combo. Beethoven, meanwhile, had also come to symbolize power insofar as mental, spiritual, and emotional authority — the triumph not so much of the will as the self. Kant would dig this, Socrates would dig this, but here we have the thorny bird of timing to contend with. And when we contend with bad timing, we also contend with notions of self-doubt, and refrains of Is there any way in which to make this work, given the context, given the timing?

Remarkably, Furtwangler, going by this version of the Ninth — which you can put alongside any other and expect it to come out on top — is totally unfazed. It doesn’t hurt to have Beethoven as the wind at one’s back, but Furtwangler is equally authorial. The music all but physically presses itself onto you and into you. The string articulation is insane for a live recording. If you break down sentences, you know that a lot of power comes from a verb. The verb is a sentence’s motor, its engine, the fillip on which so much else is dependent. In the Ninth, the fillip is often the violin section. It is the violins that hint at something larger to come, so that we all, subconsciously, feel prescient that something big is going to happen at some point. It’s a clarion call, from out of a German summer, in this instance, that we — any listener, that is — are all in on something inclusionary rather than exclusionary.

When the choir enters, you may be physically staggered back into your seat if you were standing. Even with this recording from 65 plus years ago. There was the sermon on the mount, but this was the music on the mount, free of harangues, free of marching orders, just the surging call of the human spirit to find and make space for yourself where you can, where you are best situated to be. If you love Beethoven — and you should, so give him a try — it is in the presence of this music that Bayreuth reopened himself to new possibilities — and anyone who hears it, too. •

Feature image by Shannon Sands. Images courtesy of Giftagger, ShizHao, BArchBot, The Crow & The Cross via Wikimedia Commons and Frank Avitia, and music2020 via Flickr (Creative Commons).