I often think about my deceased dog, Pokey. He was a Wheaton terrier with a genetic predisposition toward stomach problems, and he eventually succumbed to gastric cancer in his 11th year. I miss Pokey and have nostalgia for his daily routine.

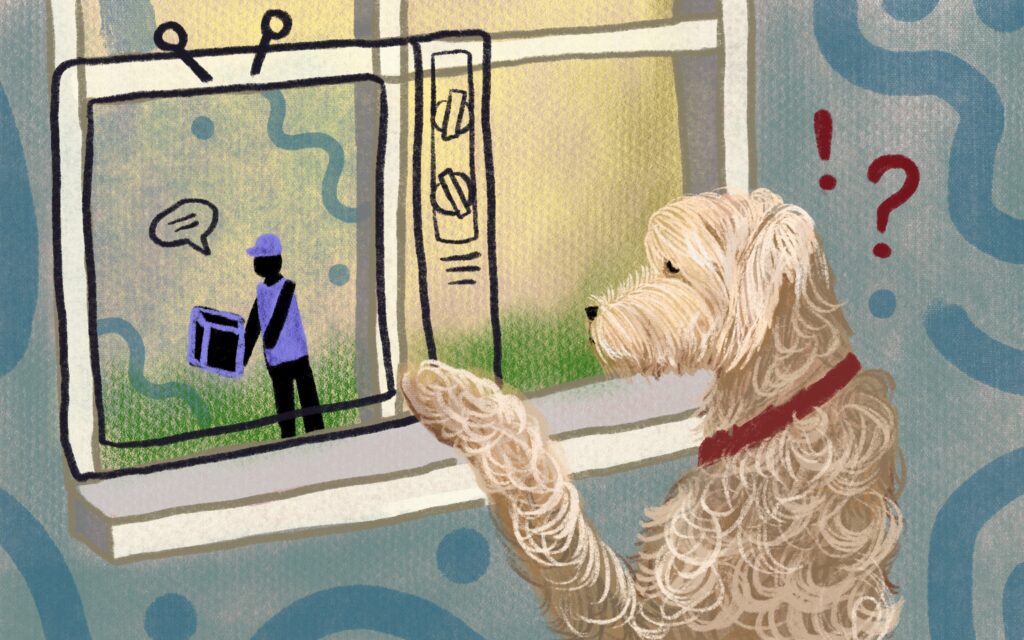

He had a fairly mellow disposition (except with the mailman and the gasman, for whom he felt unremitting enmity). Though I spent a good deal of time at home during the period of his existence, working at my computer, doing laundry, or yelling at the kids, Pokey was generally not involved with me. He preferred to sit on the top of the stairs, paws hanging over the top step, or on the window seat in the dining room, facing the window, or on the marble slab separating the bathroom from the laundry room, staring at the toilet bowl. He would occasionally move to the sofa, to the doorway of the kitchen, or to my bed (where he took particular pleasure sitting on my pillow because he knew I didn’t like it). Why, I often wondered, did he sit in these various places for extended periods of time, roused only by the sound of the mailman dropping the letters behind the door (an event that caused him to grab the hall rug in his teeth and shake it like the neck of a helpless rodent)? What, I speculated, could this animal be thinking, if thinking it could be called, during the hours and hours he spent in prone and supine postures in these various predictable locales?

It finally occurred to me that my dog was, in a manner of speaking, at the movies. I call his behavior movie-going because I think it compares with the experience humans have in a movie theater. Pokey seemed to me to be one of those fanatical cinephiles who go to double and triple features, losing themselves in the lulling embrace of the images on the screen. Each of his preferred locales was like a different theater in the multiplex that was our home. Thus, when he sat, say, at the top of the stairs, the film consisted of the steps that people in the household periodically climbed and descended. When he sat on the window seat, the running feature was the side street where cars passed, people jogged, and occasionally dogs were led by masters (at whom he barked, forgetting that this was only a movie). When he sat at the entrance of the kitchen, the movie centered on me, taking the dishes out of the dishwasher, talking on the phone, or stealing a piece of chocolate from its hiding place in the back of the drawer. When he sat facing the toilet, the film starred the shiny ceramic bowl, with special effects provided by the dripping faucet, the cool tiles, and the pungent odors that occasionally wafted in his direction.

What must be kept in mind was that Pokey, having no ability to process narrative, was therefore satisfied with mere images. New images—like my children’s friends stomping through the kitchen or an ant proceeding slowly across the wood floor—were welcome novelties, but more routine images—like the toilet bowl or the slope of the stairs—were entertaining, too. After all, there’s lots to take in when you consider all the angles and curves, the stains, the chipped paint, and so forth. No doubt Pokey was acutely aware of these details. He was, I postulate, a close reader of the kind that has not been seen since the heyday of the New Critics.

I don’t think Pokey was bored by the movies he watched day in and day out. It’s sort of like the way my kids were when they were young and liked to watch the same movies again and again: The Parent Trap, Peewee’s Big Adventure, Meatballs. For Pokey, no doubt, there was security and satisfaction gazing at great length at the toilet bowl, assured of its stolid presence in his line of vision, if with some small added touch, like a new glint of light across its surface or a new stain on the tiles where he cooled his paws.

I sometimes felt guilty that my dog, who descended from a breed of Irish sheepherders, was so sedentary. His forefathers ran over hills and dales, feeling the wind whip at their coats, exerting their authority over the stray sheep. They were dogs of action, who lived their lives in the open. But the breed was discovered by a dog entrepreneur and was subsequently judged an excellent house pet by the American Kennel Club. Soon, the sheepherders had all been shipped to suburbia and gotten hooked on movies.•