I was only about ten when my mother returned from visiting her aunt in a lavish New Jersey rest home and said, “That’s my worst nightmare — not knowing who I am.”

I’d been on one of these visits myself to what looked like a Colonial mansion out of a movie, and was dazzled by the gigantic parlor filled with bright chintz-covered chairs and sofas. It looked as big as our whole 1930s-era apartment in Upper Manhattan.

Everyone seated in this imposing space was a tiny elderly woman with white hair. They looked so much alike they could have been related and I felt a bit frightened by the eagerness with which they stared at me. Did they hope I was visiting them? Or was it my raw youth they envied? My mother’s aunt needed to be reminded who I was, and her blank stare was like a castle wall that could never be breached.

“Not knowing who I am,” my mother said. “There’s nothing worse, except forgetting how to speak.”

I couldn’t imagine my mother silent like that because our home was a linguistic hothouse. My Polish mother and Czech father spoke almost a dozen languages between them, fluently and volubly: French, Flemish, German, Russian, Polish, Czech, Ukrainian, Serbo-Croatian, Rumanian, Yiddish — and English, of course.

Dad had picked up his English in New York working in the garment industry with men from Brooklyn and used “dese” and “dem” for “these” and “them.” Anyone he disliked was a “bum.” And having grown up on a remote farm in the Carpathian Mountains, his speech in that language was rough and percussive.

My bourgeois mother learned English after WWII in Belgium from a tutor born in England, and there was always an exotic edge to how she spoke: she never sounded like any kind of New Yorker. Her sentences were clipped and precise, and she actually seemed to love the sound of English. She also pronounced her t’s distinctly in words like “butter” and was proud of her “th,” a sound many Europeans have trouble with.

The way she spoke was inspiring and a little intimidating because her manner bordered on the majestic at times. A shapely 5′ 7″, with waves of auburn hair and perfect posture, she often had the aura of a hostess welcoming guests to a very exclusive party. Or maybe something a bit grander: a deposed ruler of some tiny principality maintaining the aura of a court that had abandoned her for their own safety. Her judgments about everything from politics to fashion were swift and unyielding; her smoker’s laugh, by contrast, was unfettered and very human.

Her parents were socialists, and she was a feminist, though I didn’t realize it at the time. She believed in a woman’s right to choose and was unashamed about having had an abortion soon after the war “because I wasn’t ready to start a family.” And she lived with my father for a full year before agreeing to get married, advising me to do the same when or if I found someone I loved enough.

I was fiercely in love with her from as far back as I could remember and especially impressed with her ability to move from one language to another like a champion swimmer doing a perfect flip turn. When she and fellow Holocaust survivors gathered to play cards, the air was a riot of many Eastern European languages, and there was a kind of magic glow around them that could also feel like a force field.

They had survived horror, yet here they were telling jokes, feasting on pastries, fruit and vodka on their breaks, talking with delicious detail about the game and their luck with the cards or lack of it, and eyeing me as speculatively as the Reverend Mother eyes Paul Atreides in Frank Herbert’s Dune. I wasn’t tested, but I was clearly surveyed: what sort of son would I be? How would I carry on the legacy of a people whom Hitler and the Nazis had almost destroyed? I felt their X-ray scrutiny and suspected that I was just a shadow of their vanished past in Eastern Europe. How could I be anything else?

I remember those poker nights as a festival of sound and life. Despite the tragedies they had lived through, this band of survivors never looked defeated or depressed — and perhaps that was because they took strength from each other.

My mother’s own strength, which could sometimes cross the border into bullying, was a rock for me as a child. I knew just enough of her history of torment and torture in the Holocaust to marvel at how very normal she seemed at times. Especially when I read some news story about abusive parents locking their children in closets or tying them to radiators.

“You’re so American,” she sometimes said to me, disapproving of some idea I expressed or even just a toy I wanted because all my friends at school had one. It was a verdict I couldn’t escape. Though not as chilling as when she dismissed some neighbor as a “fishwife,” a politician she disliked as a “viper” or anyone at all as a “behaymeh” — Yiddish for a creature, a terrible person.

There was an authority in these labels as impressive as the view from our 1950s nondescript kitchen, because it faced north to the massive hilly uptown cemetery of Trinity Church, filled with aged, impressive mausoleums and trees that seemed to soak up their stony gloom. In this dimly-lit room I had after-school milk and fresh-baked golden sugar cookies — her specialty — and she would occasionally talk about her own childhood. That Formica-topped table was a smaller, more intimate version of the one at which she merrily played cards with her friends, and I always felt sheltered there, welcomed and enjoyed.

Somehow, over more than one afternoon when I was around 12 years old, and maybe just because I asked and it amused her, she shared curses and insults in Polish, even though she said there was no reason to learn such a difficult and not-very-useful language. After all, who spoke it? And it was filled with linguistic brambles: “bedsheet” in Polish was the mouthful prześcieradło. And she laughed: “What a language with its psh- and sh-sounds!” But she spoke it growing up in Wilno (now Vilnius), and in my clumsy way, I suppose I wanted to enter those lost years of hers without realizing that was my wish.

So with wide eyes and uplifted chin, she jauntily taught me some Polish, swearing as if she were a museum curator proudly displaying locked-up treasures to a VIP. Her favorite translated to “shit on a stick”: gówno na patyku. Then there were the expletives jasna cholera and cholera czemshka, equivalents of “goddammit!” or “holy shit!”

Dupa wolowa meant “idiot” or “dumbass,” but her favorite was the bizarre yet very common “dog’s blood,” psia krew, which she used as an all-purpose cry of frustration. And she even made one up just for me, or perhaps it was her own invention as a little girl: “rotten dishrag,” zgniłe ścierki, which I won’t even try to transliterate.

Where did that fit in her universe of opprobrium? I think it was closer to fishwife than viper or baheymah. And where did these lessons fit that were nothing like helping me with math or French homework?

She told Polish jokes too. That is, jokes Poles themselves told before the war, and she could stretch them out like a classic comedian on the Ed Sullivan Show. Her favorite was about the peasant woman in confession who begs her priest to tell her husband to use a condom. “But my child, that’s a sin! Why would you even think of such a thing?” “Father, someone told me that every fifth child in the world is Chinese and my husband and I have four children already — what would the village say if I had a Chinese baby?” She’d tell it differently each time with new twists and turns and I felt cherished in ways I’ve never experienced since: this was a glimpse into a culture I could never know, but whose quirks she seemed to relish despite Polish anti-Semitism between the wars. It was, after all, her home, vanished now like Atlantis. The cemetery where family graves went back to the 1600s had been paved over by the Nazis or Russians — or both.

Those afternoons glowed with talk of all kinds. She could discourse on any topic, which oddly made her very American, or certainly very New York, as opinionated a city as you’ll find anywhere.

•

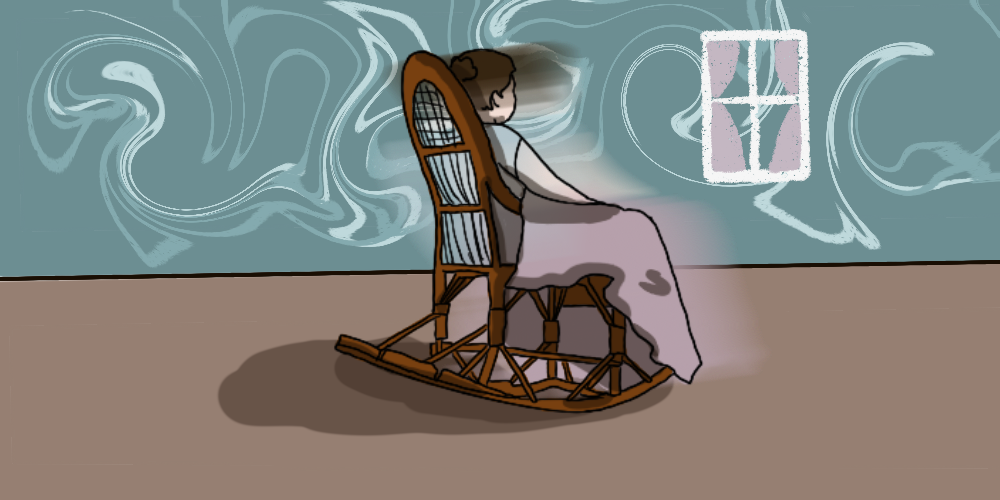

The onset of stroke-caused dementia in her 70s which reduced her conversation to rambling, disconnected sentences and ultimately a descent into Russian baby talk (as my father explained it), felt cruel beyond belief. What she most feared had come true. This lightning strike or illness was followed by years of complete silence until she died. I tried writing about losing her to dementia and even won an essay contest for my attempt, but what was a prize worth when I couldn’t share it with the woman who had always encouraged my writing?

Then about nine years after she stopped speaking, around 2 am, my bedside old-style desk phone rang and there was crackling silence on the other end. But I sensed something — this was no crank call or misdial.

“Mom,” I asked, “Is that you?” I kept repeating the question until she replied “I’m all right” in the heavy smoker’s voice I hadn’t heard in years, and the call ended.

The phone rang again and it was my brother telling me he’d heard from the hospital that she was dead.

I told him that I knew: “Mom just called me.”

But how? She’d been completely silent and unresponsive for close to a decade. Could she really have suddenly regained the power of speech and been able to actually reach for a phone and dial my number?

Was it a dream? A hallucination?

Or something else . . .

My grief in the following days and months was softened by that call and by the comfort of her last words however they reached me.

Illness silenced her, but death apparently did not. Her call was a gift but also a reminder of everything I had lost when her silence became something like a force field around her. I haven’t found closure. I miss her every day, miss what her take might have been on Putin, for example, since she knew Russian and could identify accents and someone’s level of education when she heard native speakers. I miss how she could take a bird’s-eye historical view of almost any situation. I miss her whenever I’m cooking because she could make anything with ease and grace — and break an egg with just one hand, a skill I have never mastered.

Most of all, I miss all those opportunities to ask her questions about her Holocaust years but was either too stunned or too ignorant to know what exactly to ask.

Her absence haunts me.

And so I write. •