A master of the American short story, Richard Burgin has, over the years, haunted us with a range of lonely, neurotic, occasionally criminal, yet weirdly sympathetic characters. Now in A Thousand Natural Shocks, we have a collection of Burgin’s greatest hits plus a few new tales, thanks to the astute selections of editor Joseph D. Haske.

Richard Burgin is the author of 20 books. He has received five Pushcart Prizes for his fiction, a distinction accorded outstanding literary work published by small presses. His book The Identity Club: New and Selected Stories and Songs was listed in The Times Literary Supplement as one of the best books of 2006 and noted by The Huffington Post as one of the 40 best books of fiction in the last decade. The title story of that collection, “The Identity Club,” was the lead story in The Best American Mysteries 2005 and appears in The Ecco Anthology of Contemporary American Short Fiction. “The Identity Club,” a tale of fraternity and fatal aestheticism, is also collected here, just one of the many best-of-Burgin stories in A Thousand Natural Shocks. In addition to his own contributions to the short story canon, Burgin is the founding editor of the internationally acclaimed literary journal Boulevard.

One of the hallmarks of Burgin’s fiction is his loyalty to his characters’ weirdness. Rarely does he seek to cure his strugglers or free them from their emotional contortions. Sometimes, Burgin’s protagonists, most of whom are men, seem baffled by their drives and obsessions. Sometimes they are fully self-aware. Often they harbor secrets. Often they live in fear. At times they are manipulators; at times they are manipulated by others. Here and there a happy ending may occur, and occasionally characters do good deeds and change, but mostly the author lets his people follow their obsessions and skewed sensibilities to their logical and grim conclusions.

Burgin’s alienated and injured characters often go to bizarre lengths to salve their wounds. Take, for example, the first-person narrator of “The House Visitor,” a man who sneaks into people’s houses when they are away. This is illegal breaking and entering, but the man doesn’t see it that way. His motive is sad and innocent: he wishes to sample for short spells the love and comfort of a family home. He never comes to steal, only to soak up the ambiance of a life lived with others. The story layers his comic-transgressive intrusions with harrowing memories of the abuse he suffered in his childhood home. On the night the story takes place, appropriately Halloween, he enters the home of a mother and young daughter while they are out trick-or-treating. Dramatic tension peaks when the mom and daughter return home and come face-to-face with the guy who manages to flee.

A less agreeable character, one more representative of Burgin’s manipulative types, drives the action in “Bodysurfing,” the lead-off story in the collection. Lee, the antagonistic protagonist of this story, is on his way down the corporate ladder and vacationing alone in Costa Rica. Lee, who, it appears, is suppressing his homosexuality, picks up a young American surfer, plies him with mai tais and fibs extravagantly about his expertise in bodysurfing. The more Lee gets to know the pleasant young surfer, the more he seems to hate him for his normalcy and athleticism. Lee, however, harbors much more hatred of himself and eventually induces the young man to follow him out into the ocean, only to be the horrified witness of Lee’s suicide.

On the other hand, the author does allow some of his characters to change for the better, and this occurs in “Don’t Think” and “Caesar,” two of the more recent Burgin stories in the collection. Told in the second-person, the speaker in “Don’t Think” reveals rapturous memories, troubling existential meditations, and romantic regrets, a litany of issues that cover almost the whole of the speaker’s worried life. As a lead-in to each reflection, the speaker commands himself not to think of the perturbations he calls to mind. Trying to dismiss unsolvable questions, he sees that what grips the soul is the human; above all, what grips this speaker is his connection, however challenged, with his son. “It’s selfish,” the story concludes, “in a way, to love a world where there is so much suffering. But don’t think of that.” Think of your son, says the speaker to himself, “of the love in his eyes. Think of all of this as long as you can.”

More dramatic and tense and ultimately uplifting is the new story “Caesar.” Here Caesar, a gay man, picks up a cab driver and invites him for drinks in a luxury hotel (the drinks-with-stranger thing appears to be a trope in Burgin’s fiction). The cabbie, who is not gay, senses Caesar’s subtle advances and flees. Next comes along a debonair homosexual man who picks up Caesar in the same luxury hotel and buys him drinks. Terrified by the man’s sadomasochistic proposition, Caesar takes flight. Caesar’s third encounter is the most dramatic. Having escaped the S&M man, frightened and jittery, Caesar makes his way back to his house in a snowstorm. In the howling wind, he hears the cry of an elderly woman who has fallen on the icy sidewalk. Uncertain of his physical strength, Caesar manages to pick the woman up and carry her a few houses down to her son’s home. A good deed done, a new neighbor met, warmth and inner peace melt over Caesar’s soul at last.

Flight is a common feature in a number of the stories, and this is true of the ending of what I see as Burgin’s masterwork, “The Identity Club.” Lonely, fairly new in town, in need of friends, Remy, 29, a copywriter at a New York advertising agency, is on the brink of being accepted into a secret society known as The Identity Club. “Its members,” writes Burgin, “assumed the identities — the appearance, activities, and personalities (whenever they could) — of various celebrated dead artists they deeply admired.” One member is Edgar Allen Poe, another the composer Eric Satie, another the jazz pianist Bill Evans, and so on. Remy is about to be accepted into the club and about to take on the persona of Nathaniel West when he discovers a few things: one is that the members must die at the age and in the manner of their new identities; the other is that it is too late for him to back out. Seized by the knowledge that he must die at age 37 and in a car crash as West did, Remy makes a mad dash from his workplace, which, it turns out, is an incubator for club members. Remy frees himself from the clutches of this murder/suicide cult which prizes art and artistic legacy more than life.

Horror there may be, but Burgin’s grim sense of humor also pervades many of the stories. “My Black Rachmaninoff” is high-brow hilarious, and it gets funnier each time I read it. Here Burgin’s main character is a divorced woman, again a lonely soul. She convinces herself that the rapturous concert-level piano playing she hears in her apartment is the work of Howard, the building’s black doorman. She conceives a passion for Howard and cultivates a friendship with him. The more she talks to Howard, the more she sees his love and knowledge of concert music, learns that he owns a baby grand, and gathers other details about his life, which filtered through her fantasy, add up to his being the person who plays the Beethoven, the Chopin, and the Rachmaninoff. She dubs him secretly “my black Rachmaninoff.” By and by, she invites Howard to dinner in her apartment after which she invites him to her bed. Following sex, while they are together in her bedroom, she hears the real pianist practicing. “Korean girl on the fourth floor plays that,” says Howard.

Other moments of humor spring out in bizarre story concepts, such as “The Spirit of New York.” Here the main character has a unique hobby: he likes to “scare people, usually women. I don’t hurt them, or even wish to; I simply jump out at them, or suddenly appear from a corner or doorway or behind a parked car or tree.” Funny for us as readers. Not so much to the spooked ladies. That said, the spirit is a successful frightener until his luck runs out and he finds himself frightened in return.

Some stories have comic one-liners. The spirit of New York costumes himself in various guises when he goes out to scare people adding that navy blue “is one of my favorite colors to scare people in.” In “The Follower,” the main character offers a sure cure for insomnia, “a small glass of vodka mixed with an all-night dose of CSPAN.”

Richard Burgin’s protagonists are often difficult people: troubled, strange, alienated souls adrift in the world of the married, the friended, the professionally successful. Their attempts at making connections, friendships, and sexual liaisons tend to come to bad ends. In the meantime, the ideals of intimacy, family ties, and acceptance often rotate like golden globes just out of their reach. That respect for failure is one of the many reasons why I return time and again to the work of Richard Burgin and why I celebrate this collection of his short stories. •

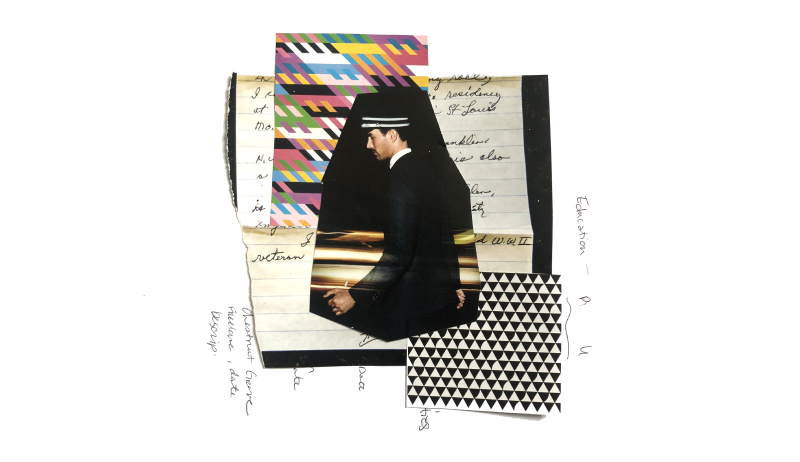

Graphics created by Emily Anderson.