When I heard in March that my university was closing for the semester, all I could think of was whether or not my partner was staying — and how, if he was, then I would have to find a way to stay, too. I felt a kind of love I had always both feared and desired, a love that made me willing to make shared decisions — even, at times, to compromise.

The night he first told me how he felt about me, we were both too shy to kiss or touch, choosing instead to dart away to our separate bedrooms. Still, a little while later, I tiptoed down the hall to his door, reached out a hand to knock, before changing my mind and scurrying back to my room and lying awake listening to love songs and smiling into my pillow until morning. Later, I found out he’d done the exact same thing.

For the next month, each day during class, I felt I was walking through a dream, glassy-eyed and unable to focus on anything but the anticipation of seeing him later. Some afternoons I’d visit him in the café where he worked, my cheeks turning red when he flirted with me over the counter or reached out to pass me a love note he’d scrawled on during his break. Each night I slept in his too-small twin bed, trying my best not to shift in my sleep for fear of waking him. I wanted to be everything he wanted me to be, flooded with warmth and gratitude when he said he felt he could tell me anything.

We didn’t go on grand dates or wild adventures. We held hands walking to campus, whispered and laughed, and had the kind of sex that gave me a new understanding of my body and desire. Sometimes, I felt too many things at once to put into words, and all I could do was tell him over and over, “I’m so happy.” He was equally my boyfriend and my friend, the person I never needed to hold my breath around or count the minutes until the obligation of spending time together would be over. I was willing to be part of him, to let him be part of me in a way that I had never felt about anyone else, fearing always dissolving my sense of self in another.

And so, because he was staying, I stayed, too.

After campus emptied, our new but rapidly growing serious relationship became even more intense. With so many of my friends gone, I felt, suddenly, that he was the person I most depended on. For a period, I cried every day. I felt unmoored and homesick, wondering if in a day or a week I would still have the choice to leave, or if travel to my distant home state would soon be impossible. I couldn’t bear to go, an act I was sure would spell the end of my relationship, but it felt equally unbearable to stay through all the late snows of March, gritting my teeth through my feelings of isolation.

Still, I held on.

Some days were beautiful; early evening he’d find me on the windowsill in the waning light, quilt wrapped over my shoulders. He’d sit on the heater or in the chair and we’d lose the remaining light to conversation. Having sex in my bed coming down from a high, sweat dripping from my brow, him looking down at me with such appreciation, saying, I live in paradise. Cooking dinner together or watching TV in my roommate’s abandoned twin bed; all the quick kisses, and the ones that lingered. It’s hard to admit to now that I’m alone and trying again to find value in what I can give to myself, but there were moments when I couldn’t long for anything beyond what I felt for him, for all those small moments of intimacy. The warmth of his skin, the knowledge that I could tell him, over and over again, I love you.

At times our schedules seemed diametrically opposed — he would wake early, while I would find myself lying awake into the wee hours, then crashing into a deep and dreamless sleep until late afternoon. When I was awake, I wanted to be outside, whether wandering the gorges in gray drizzle or scribbling in my journal on the grass of the Art’s Quad in early Spring sun. Inside our house, I felt the walls bending closer and closer, while he took comfort from watching TV or painting in the living room surrounded by our housemates. Outside, he felt tense and vulnerable, unable to relax or enjoy being in nature with me in the way that I wanted from him. Tiny things hurt my feelings. If he said he would come up to my room at eight pm, each extra minute was agonizing. In a discussion about sexuality, he seemed shocked and almost hurt to hear that, though I considered myself not-straight, sometimes the label of bisexual didn’t feel quite right either or like something I had fully unraveled in myself. I felt I had irrevocably disappointed him. Everything was ill-fitting and off; I missed him even though I knew in reality I had more time to spend with him than I did Before.

Beyond our mismatched daily patterns, we were also in completely different places in our lives. He was planning for a near future that meant starting a new job in a new city and moving out of the house that had been his home for three years (and mine for less than one). I was waiting. Waiting to be closer to some next stage, to not be a sophomore anymore; for some sense of direction or pull, or to stop longing for my elsewhere friends and dreaming of my childhood bed, calling my parents just to hear the sounds of their daily routines.

Sometimes we had arguments about him saying he’d be around at a certain time and then forgetting, or about me asking over and over for him to go on walks or sit outside with me. Then, thinking he wanted space, I avoided him, only to find out my reaction hurt him. I don’t know how everything I said or did made him feel, or what things I’d take back if I could. For a long time, we weren’t talking about what would happen when he moved or if we’d try to stay together. The date felt too far off and too intangible, the pandemic world we were living in too unpredictable to make any real plans. I noticed at some point that he’d stopped leaving me love notes, that I couldn’t see as I had before his affection for me. We had a series of long late-night conversations during which I told him I didn’t feel appreciated or valued by him the way I had once, and he admitted he couldn’t tell anymore if he was in love with or just loved me. I was sure we were breaking up. I felt feral with anguish, with a sudden certainty that I had never loved anyone so much and no loss had ever undone me as irrevocably as this one surely would. Every breath felt heavy. Each bite of food stuck in my throat. At three am walking in the graveyard, I said, Please, just tell me whether you want to be with me. He said I want to be with you.

A feeling of exhaustion and resignation came over me. He was leaving in two weeks. We sat on a bench. I said, Okay, but I feel like I should tell you when I talk about being with you, I only mean while you’re here — not after you leave. I had been sure he was about to break up with me, was sure, as much as I still loved him, that what I needed most was for the pain to end, to rip my life with him away and curl inward until I was cocooned in my own body, finally numb and alone.

I needed to go home-home for a while, to sleep under the collaged walls of my high school years, and let my parents put food on the table and comfort me, to be away from everything I associated with him and with us. Briefly, I decided to leave that same week, but when I told him, the expression of pain in his eyes was too agonizing and I changed my mind and booked my flight for the day before his friends would come to pick him up to drive together to the city where they would live.

I became obsessed with our goodbye, with how many hours we’d have together my last night, and whether or not I would know when we were sharing our last kiss. After a week or so without physical intimacy, I got too high from a friend’s edible and he came upstairs to comfort me. We started kissing and I felt it everywhere as if I were drowning as if I’d been given what I most wanted and was most terrified to lose. I thought of the relief of the first night we ever spent together, how I couldn’t believe I was allowed to touch him, to lean my head on his chest and feel everything I’d been holding back from feeling in our friendship. I started crying. I needed to be told over and over that he wanted me in order for me to believe it. I don’t know if I’ve ever felt so guilty and pained as when he pulled back from me and asked, You mean you don’t feel loved by me? We both hated hurting each other. Maybe the measure of love is when, as it’s ending, you wish you could take all that person’s share of pain, even if it doubled your own.

I began having nightmares where I woke in the morning and he had already left, or where we had said goodbye, but I didn’t realize it was goodbye and treated it as if one of us were merely stepping out to go to the grocery store. I wanted so many small confirmations that he couldn’t give me. He didn’t want to choose times of day or of night, to promise specific hours to each other. I felt there was nothing and no one to hold onto, that I was carried by a current that rendered my body weightless. And then we were kissing at the airport, and then just as quickly it was over, and my body was floating over the country, my skin as frail and light as a moth’s wing.

I don’t really know what to take away from this process of loss, of trying now to be friends in a way that doesn’t ache. I don’t know whether to blame the pandemic for our strange and opposite schedules, for the distance that grew between us. I don’t know whether I have a right to my hurt or what apologies I owe or am owed. It’s hard to work through what months were joyful and which painful. In reality, I think all of them had some of each, at times both at once. On one of our last mornings together in May, he held me against him in my little bed against the window. I was crying slightly, and I could feel his breath against my ear. He said I’m just trying to remember everything about this moment.

Sometimes I wish we could’ve hung on at least until the pandemic abated and it became less complicated to meet other people. Other times I think we did the right thing, and I want to tell others who are struggling or gasping for breath in their relationships that it’s okay, even now amidst all this uncertainty, to let go. Sometimes I think everything I’ve done since our relationship ended—every trail hiked, a poem written, or a drunken night spent with friends—has been an attempt at distraction, but not an attempt to move on. I feel as I sleep the presence of the shoebox under my bed, bearing all the letters and objects he gave to me. I feel all over my skin the places where he once touched me and I think of him in each room of the house that, until he drove away, I never knew as other than ours. I don’t know how to define myself now, this girl living through a pandemic and the end of a relationship with someone I loved so deeply.

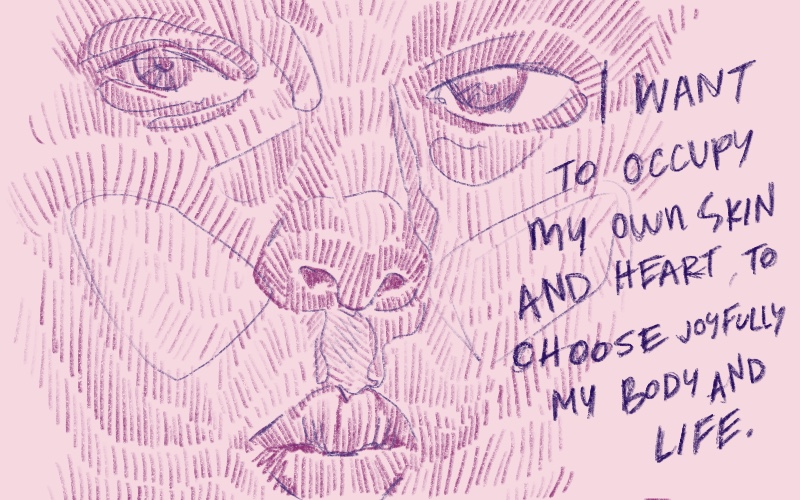

I don’t know what words to say or write that can snap me out of this holding period and carry me forward, and I don’t even know how much of that is about him or about this moment. I want most of all to feel I am choosing to be where I am — whether that is this house or the next place I’ll go. I want to occupy my own skin and heart, to choose joyfully my body and life, which is all that is ever — and barely — guaranteed. •