In 1817, a former forester by the name of Karl Drais undertook an excursion on the paved road from Mannheim, Germany to Schwetzingen, just west of Heidelberg, and back. These eight miles took him just an hour (a stagecoach would have needed about four). Instead of merely walking, he drove himself or rode on a special vehicle he had constructed for himself: the Draisine, or dandy horse, made from wood. The local newspaper didn’t even take notice. We don’t know if Drais was aware of the importance of his vehicle, which we remember today as the prototype of the first bicycle — in other words, the first mechanical individual means of transportation without a horse.

The revolutionary aspect of the Draisine was the fact that it had two wheels in a line rather than next to each other. Drais acquired something like a patent in his home state of Baden, and later in Prussia and France. However, his invention was not yet a bike in the sense that we know today. It didn’t have pedals yet, and was propelled by the rider pushing on the ground with his or her feet. This direct connection with the ground gave riders the feeling of being somewhat in control, while the bike as we know it today requires more trust in the device. It was something the people back then simply didn’t have.

The Draisine still met with a lot of resistance. Doctors had reservations, too, because they believed that riding the curious vehicle could provoke sexual excitement. It was seen as a danger to pedestrians and was banned in various places and even entire countries, deterring its wider use for more than half a century. As the functioning principle didn’t have a model in nature, it was somehow seen as an affront to common sense. As Drais mentioned at one point, his invention was inspired by ice skaters, who don’t tip over despite the thin blades on their skates. People kept asking themselves: How was it possible to keep one’s balance and not fall? Drais also realized that the rider would need to be able to steer the front wheel.

A revolution was under way. The first two-wheelers were leisure-time toys for aristocrats, the only people who could afford them. It took another 80 years until the bicycle became a means of transport for the masses. The development continued as the “running machine” morphed into a much more sophisticated apparatus, now made from iron. And its history spans continents. From Germany it went to France, from there to England and America, and then on to Taiwan, China, and Japan before it conquered the rest of the world.

But we should not have any illusions about the character of these early vehicles — these “bone shakers” were not bikes in the current sense. The name was most likely not an exaggeration, either: With tires made of solid rubber or iron, they left riders with a painful feeling after rumbling over cobblestone pavement. They were also heavy, easily close to a hundred pounds. A major problem was that one turn of the pedals translated into one turn of the tire, which limited the vehicle’s speed.

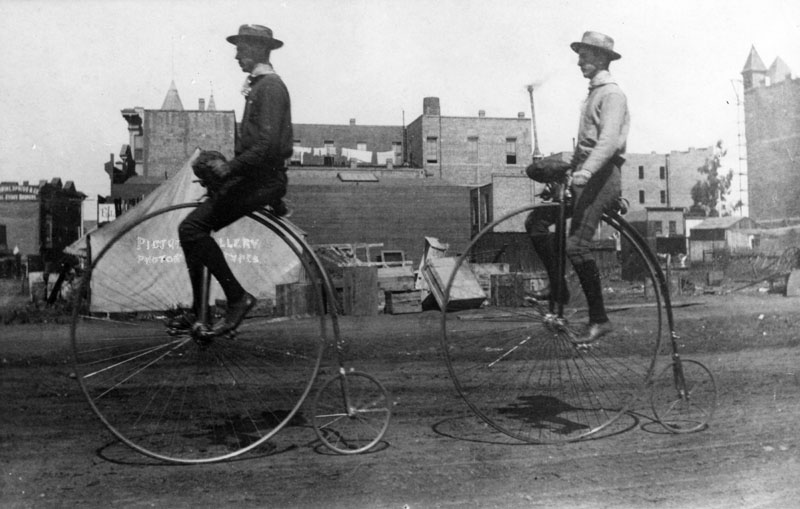

In the 1880s, inventors created vehicles that, in retrospect, appear to be dream-like mutations: high-wheelers or “penny-farthings,” which finally deserved to be called bicycles. High-wheelers were a short-lived fad; they just weren’t practical and their use entailed a number of health risks, such as being thrown backwards while riding uphill. (The use of modern bikes is not entirely without risks either.)

But the positive aspects associated with riding bicycles eventually gained the upper hand: People realized that cycling could be an appropriate means to train one’s body control and develop a sense of self-reliance. And it was another way to measure one’s own limits — would it be possible to make it up that hill? Last but not least, cycling became the first popular athletic pursuit for women, with bicycle manufacturers producing ladies’ models.

When the veterinarian John Boyd Dunlop, a Scotsman, revived the idea of pneumatic tires, observers made fun of him, but by the late 1880s all bicycles had them. And by 1890 there were about 150,000 riders in America alone. At that time, bicycles still cost about half the annual salary of a factory worker, which explains their limited popularity. Just five years later, the price had dwindled to a few weeks’ wages. Bikes had already gone into mass production, and a full third of all patents registered at the US Patent Office in the 1890s were somehow related to the bicycle. It even had its own patent building in the capital. For the first time, the working class became mobile. Now, a million people become bike owners every year.

We should also remember that without the bike as a “germ cell”, the automobile would hardly have been fathomable. Yet Drais is hardly ever mentioned in this context, as both Carl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler sound more plausible. On the other hand, Henry Ford cycled to work while developing the Model N, precursor to the legendary Model T. And as the automobile historian James Flink put it: “No preceding innovation — not even the internal combustion engine — was as important to the development of the automobile as the bicycle. Key elements of automotive technology that were first employed in the bicycle industry included steel-tube framing, ball bearings, chain drive, and differential gearing. An innovation of note is the pneumatic bicycle tire.”

Do we need any more praise of the bike? Once we learn how to ride a bicycle — preferably at a young age — we don’t unlearn it. In this respect, it’s just like swimming. As we sit firmly on the saddle, steering the handlebars resolutely, the horizon widens and the landscape around us starts to move. The sensation represents nothing less than the reunion of man and nature. Riding a bike means embracing technological progress while still relying on human muscle power. Aided by the transmission of force achieved by the drive system, the bicyclist pedaling with bent back remains a part of nature who — by means of his device — can move about and experience the space around him differently. Some say that there is a special communion between bike riders. The force the rider is required to perform equals the movement of the whole. It’s a mechanism based on cause and effect that can be understood, at least approximately, even if you don’t happen to be an engineer. And it’s a mechanism that, assuming a certain level of technical talent, one may even be able to fix.

Furthermore, once the energy needed for its production is accounted for, a bike doesn’t leave an ecological trace or footprint. Just a slim skid mark in the mud, sometimes. Or some drops of sweat. It’s a beacon of hope for urban planners and the expression of a new individual lifestyle — one already evident in countries like the Netherlands or Denmark, where bikes and cars coexist as equals, at least in the urban context. People there know that for short distances of up to three miles the bike is the perfect and quickest means of transport. And it’s reassuring to know that once all the fossil fuels have been used up (assuming we are still able to breathe, then), we will still have our good old bikes!

My own bike from a famous French brand is a full 20 years old now. Everything has been replaced except the solid aluminum frame of beautiful dark blue. Never learned to ride a bike with one free hand, though. Am I missing something? •

Images courtesy of the Tomaž Štolfa , Conal Gallagher, Judy van der Velden and Robert Couse-Baker via Flickr (Creative Commons).