“The medium is the message.”

—Marshall McLuhan

1. Nimoy (5:50 a.m.)

It’s a cloudy August morning just after sunrise, and my family and I are speeding about a hundred miles west of London in our rental car, bisecting the Salisbury Plain on the A303. Giant figures the color and heft of elephants appear on a treeless green hill, and an instant snaps before I recognize what they are. “Stonehenge! Hey, is that Stonehenge?” my son asks, my partner swerves as he takes a look, and I answer with a choked up, “Yes!” Latent emotions flood my system with embarrassing force, like I’ve run into a love-defining first crush.

The big stones are gathered in a circle as if around a watering hole, a campfire, some leaning into each other, others toppled over like they’ve had a few too many. I’m seeing them for the first time in person, and their jagged outline seems both familiar as my own hands and mildly hallucinated, as if the site had appeared from a distant universe made suddenly material — a fragment of a 5,000-year-old world.

Who built Stonehenge, how did they do it, and why? As a kid, I’d adored Stonehenge for these unsolved mysteries that had cleverly perplexed adults for so long, as if it were a benevolent entity visiting us continuously from the deep human past, wishing we could understand its heavyweight, three-dimensional language. I’d absorbed as revolutionary fact the beloved shlock 1970s TV documentary show, In Search of . . . the Mystery of Stonehenge, in which host Leonard Nimoy reported that the site was built as a mystical astronomical clock, whose time we could now tell using the most cutting-edge, van-sized computers (the results, I’m sorry to note, were a little off — but more on that later).

Like a powerful magnet, Stonehenge has long attracted alluring, brilliant, and whack-job theories. It predates the Egyptian Pyramids by five centuries and holds the lead for mystery: No indigenous written language — hieroglyphic or otherwise — remains to explain any of it. In lieu of scriptural clues or contemporaneous accounts, the site has inspired all manner of legend, science, technological innovation, spirituality, astronomical measurement, projection, mythology, and abject nonsense to explain it, rising like so many scaffoldings visible only to the believers.

True to form, I’d made my family awaken before dawn to visit the place because of my own pet interests. I am fascinated by prehistory, for exactly the reason I am weary of my smartphone. I’ve visited dozens of Neolithic sites across the British Isles, for the same reason I’m bored of addictive Internet searches. I am no Luddite, nor do I yearn to wear rawhide, live in a cave, or lack decent dental care. But I wonder: What is the cost of digital technologies meant to save us time — but which often so distractingly waste it? What of ourselves do we lose to “smart” devices, to this Silicon Age where artificial intelligences often rush in before our natural ones?

We don’t say anyone came from a primitive society anymore; we say they had primitive technologies. But these simpler technologies may have engaged all the genius, complexity, and insight human beings can muster. If the medium is the message, then Stonehenge’s built landscape — one requiring an estimated ten million work hours to construct — telegraphs at the least a major belief system capable of directing such extraordinary creative labor. What can we discern of this belief system from recent large-scale excavations at the site? Could it enrich or illuminate our lives now?

And so, as my family drives into the Stonehenge Parking Lot, I search my smartphone for the email with our ticket number to enter one of the oldest buildings still standing on the planet.

2. Target (6:05 a.m.)

Our time to visit Stonehenge begins at 6:15 a.m. and lasts for one hour. Months earlier, I’d made arrangements for this “Stone Circle Access” — time-slots limited to 30 visitors that get you close enough to touch the stones (though touching them is a no-no) and held in the early morning or late evening. If you show up during normal visiting hours, you can only view Stonehenge from behind a fence — like the stones are zoo animals kept in their own special habitat.

We park and head toward the small crowd waiting by a shuttle bus outside the gleaming Visitors Centre. The stones are nowhere within view, tucked far enough behind a long-sloping hill due east to justify the shuttle bus. And I’ve realized the hot competitive logistics required of our next several minutes.

Because here’s the silly yet pressing concern of going to Stonehenge with your kid: You might want a photo of your child standing among the stones like you just stumbled upon the place, magically free of anyone else milling around.

In order to do this, you must be willing to race the other visitors to reach the site first.

I whisper my plan to my family, and my son nods and assumes a poker face. We loiter by the reproduction Neolithic house, while everyone else files on to the shuttle. Then I make sure we are the last to hop on, so that — in what comprises the entirety of my cunning plan — we will be first off.

The shuttle sweeps us over the mile-and-a-half hill line, and I get the sensation of time-traveling in place, as if we are now entering 3000 BCE in our climate-controlled pod. Shafts of sunlight break through clouds over the Salisbury Plain — which once qualified as a sort of prehistoric New York Greater Metropolitan Area, its yellow-green landscape studded with thousands of Neolithic and Bronze Age sites including standing stones, burial mounds, and hundreds of houses.

When the shuttle stops, my son and I leap out, gape at the Stonehenge skyline rising ahead of us, and shoot down the path towards it. I assume we’re in the clear, only to realize we are speed-walk racing five Nordic-looking women. But as long-distance fast-walking is my most semi-exceptional quasi-athletic talent, and with my kid jogging alongside me, we keep our small lead.

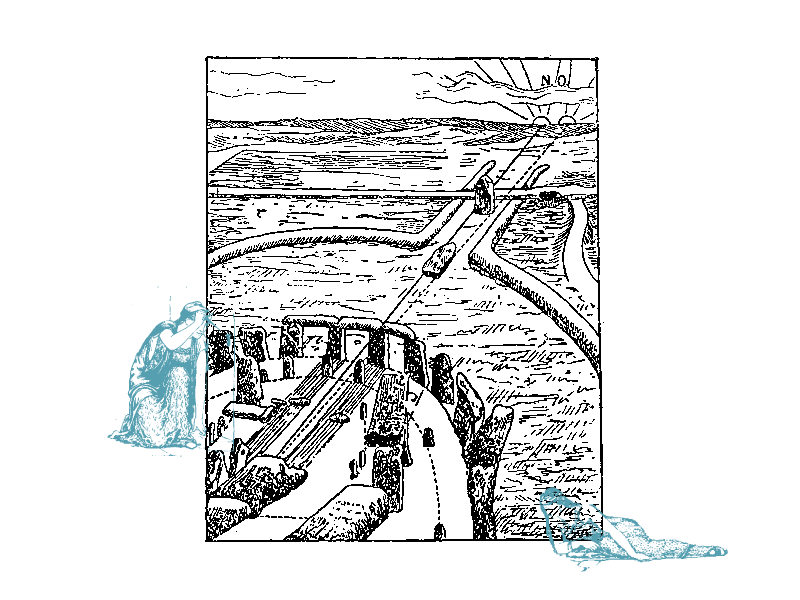

Picture Stonehenge’s layout like a huge target composed of nine concentric rings of earthworks, holes, or stones, all stretching more than 300 feet in diameter. My son and I reach the first ring and outer perimeter, or “henge” — the term for the bank and ditch enclosures that ring Neolithic stone circles across the British Isles. Its 20-feet wide impression is still visible and marks the first stage of Stonehenge’s millennia-long construction around 3100 BCE.

We then trot past the next three rings, all virtually invisible and grass-covered today. First we cross the circle of Aubrey Holes, dating to Stonehenge’s most ancient original structure: 56 evenly spaced depressions that once held standing Welsh bluestones weighing two or three tons apiece — and, as a painstaking forensic study revealed in 2016, the cremated remains of dozens of Neolithic women, men, and children. We bound another 60 feet and pass the so-called Y Holes and, several yards in, the Z Holes: two concentric rings that once held those same Welsh bluestones several centuries later, megaliths that were finally relocated to the inner circle about 4,200 years ago.

We barely beat the Nordic-looking women to the Stone Circle, where the remaining stones of the site’s five inner rings lay in a hundred-foot-wide jumble. My kid stands along the northern stretch, smiles, and I manage to get a single shot of him as if we’d rented the place for ourselves.

Then the five women dash into my camera’s view from the right and towards the bulls-eye center of Stonehenge — the horseshoe formations of massive sandstones and smaller Welsh bluestones. They form a circle, link hands, and blast away the early morning silence.

3. Stone Circle (6:25 a.m.)

In piercing, high-pitched harmony, the women are choral singing at the top of their lungs. The song sounds medieval to me, à la Hildegard of Bingen, a lilting if high-volume polyphony.

I’m delighted by the beauty of their singing, curious why they chose this piece, but just as interested to notice how carefully the other visitors, now filtering into the Stone Circle, pretend the singing isn’t happening. We are all apparently the kind of people to have studied the Stonehenge website’s instructions to visitors — “please respect each other’s time inside the Stone Circle” — and realize this is our first test. The site’s guidelines allow us to enact our own private Stonehenges through dancing, costumes, drumming circles, yoga, or whatever self-expressive means we desire — but not to query or otherwise pester anyone else about theirs.

My nine-year-old son — the only child there — is staring at the singers open-mouthed. We watch as they drop hands; their song dissolves like fog into the bright air.

Now I’m left to make sense of the Stone Circle, enough to point out the five rings to my kid: The massive sandstone “sarsens” forming the outer circle; inside that, a ring of smaller Welsh bluestones; next, the filled-in holes of the itinerant bluestones, where they’d once formed a double circle; and in the center area, two interlocking horseshoe formations — one of giant sarsens and the other, at Stonehenge’s very heart, of bluestones.

But what I see are 77 standing stones strewn higgledy-piggledy around us. From a distance and on maps, the site looks a lot more cohesive than when you’re in the middle of it. I keep turning around, trying to absorb the broken-down layout, while my first impressions of Stonehenge come in a rush.

I’m struck by how truly enormous the sarsens are — looming as tall as 30 feet, a good six or seven feet wide and deep, weighing as much as 60 tons. Honed of pale grey sandstone quarried about 20 miles away at Marlborough Downs during the Bronze Age, only 25 of them are still upright; the other 20 lay on their sides. All are proportioned like blocks to be carved with the statues of giants.

Over the years, I’ve sometimes heard it claimed that Stonehenge is disappointingly small. I now wonder if these claimants have gotten anywhere near stones, or just sped past the site on the A303, where Stonehenge does appear on the small side since it sits at a pretty good distance from the road. Because when you’re standing, dwarfed, beside them, the sarsens appear huge, absolutely massive, or as my son put it, “ginormous.”

My eye keeps getting drawn to the sarsen circle’s most finished section: The smooth unbroken line of four sarsens capped with lintels, like three linked doorways open to the Wiltshire hills (when the circle was intact, 30 sarsens once stood, forming 30 such “doorways”). And in the site’s center, the three standalone trilithons — each composed of two extra-large sarsens capped by a single lintel — resemble very tall pi signs.

I force myself to notice the diminutive bluestones, often no more than five feet high. Yet they are Stonehenge’s show-stealing stars, boasting far more interesting histories: 80 or so bluestones were once dragged or possibly rafted via sea and rivers some 180 miles away in the Preseli Hills of southwest Wales. This long-haul travel happened during the New Stone Age, which, when you remember nobody had any metal implements or even wheels to aid them, makes Pembrokeshire seem like it might as well have been Neptune.

But my most overwhelming first impression is that I’m standing in a phenomenal theatre-in-the-round: an open-air gathering and performance space in which we visitors — outfitted in our waterproof jackets and comfy shoes — are, right now, the very fortunate actors.

4. Calendar (6:30 a.m.)

I point to Stonehenge’s most famous solar alignment, “That’s the Heel Stone, lined up exactly where the Winter Solstice sun sets every year,” I say to my kid, as we gaze at the standing stone just outside the henge’s northeast perimeter.

We head to the Heel Stone and turn to face the Stone Circle. I explain how, if we were there on a clear December 21st, the setting sun would illuminate one of sarsen circle’s three “doorways” — its 30-foot high threshold blazing with orange light.

I’d already shared that Stonehenge may have been built as a three-dimensional astronomical clock — a solar, lunar, and stellar time-keeper. A beautiful old word describes such a thing: Orrery — a sort of sundial writ large, keeping track of all the sky’s cyclical occurrences. This theory is what fascinated me at his age: that Stonehenge was built to interact with both the sky and with time itself, framing and marking, reflecting and highlighting all celestial events, from moon risings to eclipses, as they marked the days, months, seasons, and centuries.

And the person most famous for trying to prove this theory was featured on my long-ago, beloved In Search of . . . the Mystery of Stonehenge: Dr. Gerald S. Hawkins, an astronomy professor at Harvard, Boston University, and the Smithsonian Observatory in the 1960s, who fed detailed measurements of Stonehenge’s architectural layout along with historical astronomical data into an enormous computer, the Harvard-Smithsonian IBM 704. He concluded from this first-of-its-kind study that Stonehenge was itself a “Neolithic computer” that predicted astronomical events, findings he published in his best-selling 1965 book, Stonehenge Decoded.

Unfortunately, much of the data Hawkins fed into that shiny IBM was wrong. Just by using then-accepted archaeology, he assumed Stonehenge’s construction began in 1900 BCE, and a good 1200 years later than its true groundbreaking around 3100 BCE — an error that throws off architectural correlations with some concurrent celestial movements. His key and very ingenious theory, meanwhile, was that the 56 Aubrey holes were used to track moonrises and lunar eclipses with the aid of two rotating wooden markers. But only from the site’s recent excavations have we learned that those holes were dug to hold bluestones, along with cremated human remains — and so were used, in other words, as burial sites.

Gerald Hawkins is far from the only Very Serious Person to have had his scientific study of Stonehenge upended by the finer technologies of future scientists. Most notable is William Stukeley, born 1687, the Cambridge-educated antiquarian, physician, clergyman, and composer who is credited, no less, with inventing archaeology as a field of study. While excavating Stonehenge, Stukeley noticed that the Summer Solstice sun rose fairly closely over the Heel Stone. He assumed this sun-drenched event on the longest day of the year must have held profound spiritual meaning for Stonehenge’s builders — whom he decided were most likely Druids. News of Stukeley’s conclusions fascinated the public, who have been showing up at Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice sunrise ever since — often by the thousands, and sometimes wearing Druid robes. The trouble is, the Druids did not build any phase of Stonehenge (their people, the Iron Age Celts, arrived in the British Isles far too late to take credit, around 300 BCE). And 21st century archaeological work indicates that Stonehenge was not aligned in particular to the midsummer day — but rather to its midwinter corollary.

But other astronomical alignments at Stonehenge have held up. I point to one the two remaining Station Stones located just inside the henge’s perimeter — they once numbered four, forming a rectangle that framed the Stone Circle. “That stone marks the major moonset to the north,” I say, “and a missing stone over there marks the major moonrise to the south. We don’t know why, but they do.”

“Cool,” my kid says. Then he whispers, “Why are those people bending over?”

5. Alignment (6:35 a.m.)

“Those people” are a couple I will silently dub the Beautiful Crunchies: A young man and woman, both sporting long flowing hair and natural fiber exercise wear, who will spend the hour striking yoga poses among the stones. I will keep finding one or the other of them Tree Posing next to a sarsen or, eyes closed, deep in Lotus near a trilithon. But right now they have positioned themselves along the Heel Stone’s alignment with the Stone Circle to do Sun Salutations.

“Yoga,” I say.

“Oh yeah,” he says, “you do that.” Then: “Why?”

“I’m guessing they believe Stonehenge is a spiritual site, and that doing yoga here will

be a meaningful experience — like they’re tapping into the energy of the place.”

He shrugs. “That’s weird, right?” he asks.

“Well, no weirder than singing,” I say. “There’s a funny old idea,” I continue, moving on to less firm ground, “where some people think invisible lines of powerful, healing energy run across the landscape — all across the world. They’re called ley-lines, and they’re not actually real,” I say, “but people who believe in ley-lines think Stonehenge is a magical center for them.”

My son looks around at the stones with a newly assessing, respectful eye. For a second, I do too. It’s fun to think magic might exist as a form of nature we don’t yet understand.

Ley-lines hit their stride as a cultural phenomenon in the 1960s — itself a sexy, peak news-making decade for Stonehenge. Another serious academic who gave the site world-wide attention in those years was Oxford University engineering professor Dr. Alexander Thom. His 1967 book, Megalithic Sites in Britain, introduced the concept of the Megalithic Yard — a unit of measurement, 2.72 yards to be exact, that Dr. Thom claimed, after measuring hundreds of ancient sites across the British Isles and Brittany, was universal to Stone Age megalithic architecture of Atlantic Europe. This suggested a cohesively developed Neolithic culture and regular peaceful contact among widely dispersed groups. But the Megalithic Yard, somewhat unfortunately for Dr. Thom and his measurement being taken seriously, was embraced by ley-line enthusiasts, who themselves tend to Venn-diagram neatly with neo-Druids, who in turn often annoy archaeologists by claiming Stonehenge as their ancestral burial ground and demanding that it be left alone. Alexander Thom did not believe in ley-lines, yet his name and his Megalithic Yard have been wound up with them ever since.

After the 1960s, no excavations of Stonehenge — or other organized on-site studies — were allowed until the 21st century. Luckily, in the past 15 years (as I write this in 2018), new leadership at English Heritage, the government trust that controls Stonehenge and many prehistoric sites around it, has allowed three major digs.

2003 marked the start of the largest excavation in Stonehenge’s history: The five-year Riverside Project. Its lead archaeologist, Michael Parker Pearson, has written fascinating books on his findings, which — in the smallest of nutshells — boils down to this: Pearson believes Stonehenge was a monument created to unite Neolithic Britons, involving as much as one quarter of the island’s population during the peak years of its construction — a kind of rural American barn-raising party writ monumentally large. And that Stonehenge, once built, functioned primarily as a memorial to their ancestors — both as a cemetery and a temple to the dead.

Then, in 2008, English archaeologists Timothy Darvill and Geoff Wainright excavated the Stone Circle for clues about the origins and uses of the bluestones. They were later able to locate the stones’ source in western Wales’s Preseli Hills — where bluestone circles much older than Stonehenge still stand, and where some local people believe the bluestone hills and the springs rising from them possess healing powers. Darvill and Wainwright concluded that the bluestones were relocated to Stonehenge for their associated curative properties, where they were used to construct Stonehenge as a center of healing — a sort of Neolithic Lourdes. The number of nearby ancient tombs containing the remains of seriously injured people who hailed from far away — the Amesbury Archer being the most famous example, a man born in the Alps during the Bronze Age — lends support to their theory.

Finally, since 2010, the massive Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project has surveyed the areas surrounding Stonehenge for prehistoric sites, including the largest dig in England’s history, Durrington Walls — work that continues to this day.

And all three archaeological projects provide fascinating evidence that two different cultures — using different technologies, and hailing from two genetically distinct peoples — built Stonehenge over a thousand-year span, possibly for several overlapping purposes.

6. Construction (6:45 a.m.)

My son now really wants to touch a sarsen, and I don’t blame him. Though the site’s guidelines are explicit, I ask one of the two guards standing, poker-faced, near us: “Excuse me, but I’m wondering: We’re really not supposed to the touch the stones?” He grimaces a brief, somehow sympathetic nod of confirmation, then says, “Let me show you something.”

The guard leads my family over to a sarsen, where he points out the word WREN inscribed faintly on its face. “Wow,” I say, and share that just the day before in London, we’d seen Christopher Wren’s masterpiece, St. Paul’s Cathedral.

“It’s a beautiful place,” the guard affirms, “but how would Wren have liked it if someone wrote graffiti on his building?”

I nod, keeping to myself how charming I find this graffiti — because Christopher Wren is the greatest English architect many of us might name, his 400-year-old defacement of a sarsen seems basically acceptable to me. But I suppose if you’re a guard at Stonehenge, you don’t want anyone getting any funny ideas along those lines. First Wren, then who?

The guard and my partner launch into a spirited discussion about the construction of the sarsen circle and trilithons. My son, excited, joins in. The guard tells us about the successful experiments to replicate the raising of these giant stones involving deep pits, enormous wooden platforms, and a tip-and-lift, shove-and-heave methodology. They all three start shuffling around, lifting their arms to mimic lifting the stones — a pantomime probably done for centuries in honor of this bunch of hewn rocks.

I went to the Egyptian Pyramids at Giza when I was about my son’s age, and remember a similar conversation and pantomime involving my dad about how the colossal stones were put in place using scaffolding, ramps, and a lot of slave labor. At the time, I was totally convinced that this could be done — because, after all, clearly it had been.

The guard points to a lintel, or crosspiece, capping two uprights in the sarsen circle. “They carved the sarsens as if they were wood,” he says. Specifically, they used the mortise-and-tenon system of woodworking: Each lintel features two holes, or mortises, centered along the bottom at either edge, which fit perfectly into the little knobs, or tenons, jutting up from the top of each sarsen. So for some reason, the sarsens were fitted together using methods of carpentry.

As for transporting the sarsens from their source at Marlborough Downs 19 miles away, modern reenactments employing a single 30-ton stone, huge log sleds, ropes, and about 200 people working 12 days straight have done the job. Meanwhile, experiments to replicate loading the Welsh bluestones onto boats and rafting them over long distances — from coastal western Wales to Bristol, then via rivers to Stonehenge — have utterly failed: The three-ton stones sink. The bluestones again prove more mysterious than the flashier, more photogenic sarsens.

But the Stonehenge Riverside Project also revealed much more accurate dates for the phases of the site’s construction — which in turn shed new light on the people responsible for them.

Stonehenge was originally built by Stone Age people: Neolithic farmers who broke ground at the site around 3100 BCE. They brought the bluestones from western Wales — where they themselves may have originated — and used the the silver-blue megaliths to construct Stonehenge’s earliest stone circle in the 56 Aubrey holes. Inside those holes they’d first placed cremated human remains.

Then, over the next five or six centuries, this ethnic group disappeared — replaced by a genetically distinct people known as the Bronze Age Celts. Since no signs of battle are found in the archaeological record, the bluestone-builders may have been decimated by plague or other disease brought by the later-arriving Europeans.

These Bronze Age Celts are responsible for building the sarsen circle and the massive sarsen trilithons around 2600 BCE. They not only kept the bluestones, but moved them ever closer to the heart of the site, suggesting that these people understood and respected their ancient symbolism.

And new studies published in 2017 in Smithsonian Magazine, BBC News, and elsewhere suggest that at least one of the bluestones’ uses was making music.

7. Choir (7 a.m.)

My son is standing next to a bluestone twice his height, his ear barely an inch from it. He calls to me, eyes wide, “Mommy! The stone is making sound!”

I join him, listen close — and too hear a very faint ringing, like an echo or some auditory effect created by the wind blowing against its surface.

This is not insane. Local boy Thomas Hardy wrote in Tess of the D’Urbervilles, published 1892: “If a gale of wind is blowing, the strange musical hum emitted by Stonehenge can never be forgotten.”

Stonehenge’s possible acoustic properties have inspired a lyrical theory: That the bluestones were relocated from Wales because they can be played as musical instruments. If you smack a sandstone sarsen with a stick, it sounds like a dull thud. But do the same to a bluestone, and it emits a clear, low ringing that can heard as far as half-mile away. Rocks used as bells are called lithophones, and bluestones have indeed been used as church bells in Wales for many centuries. Study of megalithic sites for such effects have spawned a new field of prehistoric study: Archaeo-acoustics.

And an old name for Stonehenge, Côr Gawr, may provide another clue.

Among local people and through the 19th century, Stonehenge was often called Côr Gawr (or, spelling-wise, any combination of Côr/Choir with Gaur/Gawr). I first ran across the term in Emerson’s account of his 1848 visit to Stonehenge, where he notes, “Choir Gaur, or Côr Gawr, meaning Giant’s circle or temple, is only a British name for Stonehenge.” By “British,” Emerson meant the Gaelic-speaking people living in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons began colonizing the island in the 5th century, the latter dubbing the place “Stonehenge.”

How ancient a term is “Côr Gawr”? In modern Welsh, gawr means “giant” while côr translates to “choir.” Gaelic languages like Welsh date at least to the Iron Age Celts, who started arriving in the British Isles from Gaul around 300 BCE — bringing the culture we’ve long associated with all things Celtic.

But linguistic researchers like Dr. Peter Forster of Cambridge University and Dr. Alfred Toth of University of Zurich believe the much older Bronze Age Celts spoke a root form of the Gaelic language family called “proto-Celtic,” which they may have brought to the British Isles as early as 3100 BCE. Could the name “Côr Gawr” date that far back? We’ll probably never know if these words survived so many centuries as some place-names have, broken or corrupted but still identifiable, like fragments of ancient pottery or bone.

8. Myth (7:05 a.m.)

Until the last century, the most popular Stonehenge origin story was that Druids had built it. Archaeologists today are absolutely clear on the subject: Druids did not build Stonehenge. These mysterious religious figures arrived in Britain a good 2,000 years too late to take credit — as the latest iterations in carbon-dating, forensic anthropology, and genetic testing have proven.

Druidism was the religion of the Iron Age Celts — those Gaelic-speaking tribes, dubbed Gauls by the Romans, who arrived in Britain around 300 BCE. Inconveniently for historians, Druids, though literate, maintained an oral tradition for their own cultural heritage, so what we know about their beliefs and practices comes from outsider sources — and usually their mortal enemies, the Romans. Classical writers such as Julius Caesar and Pliny the Elder claimed that Druids were priests and priestesses who worshipped nature, holding secret ceremonies in sacred groves; they were the “learned class” of the Celts; and they engaged in the occasional, blood-drenched human sacrifice.

So why are Druids so strongly associated with Stonehenge? Because the site’s early archaeologists of the 17th and 18th centuries, including William Stukeley and John Aubrey (for whom the ring of stone-holes is named), made the educated guess that Druids must have built the place, since their Celtic tribes were, at that time, the earliest known inhabitants of Britain.

The idea stuck. And it captured the public’s imagination, lending Stonehenge the romance of an ancient, exotic spirituality based on poetic language, magical rituals, and the natural alignments of seasons and astronomy. All of this helped fuel the Celtic Revival that would spread to Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, lasting well into the 19th century.

But when my family walks over to the mattress-sized slab called the Slaughter Stone — thus dubbed for supposedly being the site of human sacrifices, officiated by white-robed Druids — I have to explain to my son that: No, nobody was ever slaughtered here. Archaeologists have found nothing to indicate a crime scene.

“So why’s it called a Slaughter Stone?” he asks.

“People have active imaginations,” I say. “Sometimes they want things to be gory . . . because it’s gross and exciting.”

He nods: Of course people do.

Before the Druids-built-it theory took hold, Stonehenge’s longstanding origin story involved Arthurian legend. Geoffrey of Monmouth, the 12th century Welsh historian, recounts in the colorful and quasi-factual The History of the Kings of Britain that Merlin had stolen the stones from Ireland, where they’d form a mountaintop circle in “Killaraus” and were valued for their “medicinal virtue.” Using ingeniously devised “engines,” Merlin helped the British transport the stones to their current site. But Geoffrey also notes that these stones originally came from Africa, from whence the Irish had gotten them. This all sounds so nutty to modern ears we don’t think twice about dismissing it.

But myths like these may transmit garbled truths within the fictions. What memories or desires could be buried in them?

Why, for one, does the story involve Ireland? Stonehenge’s bluestones did indeed come from an equally and improbably faraway location, though from coastal Wales rather than an Irish mountain.

Why Merlin? Arthurian legend sites are so widespread in southwest England and Wales, it can seem comical: Merlin is buried in at least a dozen places. And many of these Arthurian places — in Wiltshire, Somerset, Devon, Cornwall — are located exactly where megalithic stone circles and passage tombs are found, including many “Excalibur stones” that were originally Neolithic standing stones. This striking overlap may suggest a root connection between these stories and prehistoric sites (including Merlin’s own pre-Christian incarnation as a Celtic deity).

Finally: Why Africa? It could just reflect a cultural desire to seem “worldly.” But I will add that once, while in Tunisia visiting a museum exhibition on Carthage, I was startled to see a map of the Phoenician tin trading routes circa 3000 years ago — one that stretched all the way to southwest England. It seems Africa was not so distant from Britain in ancient times.

“Anything goes” is not the answer to Stonehenge’s mysteries. But neither is discounting outright all the beliefs it has captured over the centuries, like a magnet collecting metals both common and rare. 5,000 years is a very long time for people to have paid attention to a single, human-created place, to have recreated its history, over and over, and with so many meanings.

9. Medium (7:10 a.m.)

Even just an hour at the Stone Circle has felt like an improvised performance of exploration and imagination. But now we’re boarding the departing shuttle bus with all the other visitors — who will be featured in my photos of the place, somehow as prominently as the stones.

Soon my family will drive to Woodhenge, the remnants of a wooden-post version of Stonehenge about a mile northeast and dating to the Bronze Age. And there, further up the road, we will run across the largest archaeological dig in England’s history: Durrington Walls, a long-buried Bronze Age village that housed the people who built Stonehenge’s sarsen circle and trilithons. The site contains at least 500 houses and evidence of massive barbecues that daily fed thousands of people. But this peak inhabitation only occurred over about a 50 year span, starting around 2600 BCE — and, more interestingly, only during the winter season, centered around the December 21st Solstice.

What the Durrington Walls site shows us is that those prehistoric builders and their families poured everything they had into Stonehenge’s construction — vast quantities of livestock and grains, stonemasonry and woodworking skills, ingenious engineering and architectural planning, and precious good years of their own brief lives (people then rarely lived past age 30). Since soft available metals like copper, tin, and gold did them little good in construction, the technology they used was stone.

It can seem funny to call honed rock a technology — a word we now elide with digital apparatus and virtual media that swiftly collect and transmit unimaginable quantities of data. Our current technologies, in fact, stand as the symbolic opposites of stone: Instead of rooting us to a single place or time, they grant us endless quick escapes to the near future, like always-waiting express trains out of the present moment and spot. And while they save us time in all manner of communication, commerce, and entertainment, they also dazzle our attention, flooding sugar-rushes of easy data that often eat away the time they’d saved us, and then some.

We like these technologies, or at least allow them to proliferate, because they mimic reality well enough, save for one crucial element: Time flattens into an endless digital scrolling, a stamp on an email, text, or post, divested from any natural cycle. If it feels lifeless, it also seems deathless. All our digital bits and bobs — our logged-in keystrokes shedding like hair — are immortal in cyberspace.

But there’s no avoiding this: Time is the medium through which we live. It’s the messages we shape from it — our arts, cultures, technologies — that change: The myths we create, the structures we devise, the beauties we observe about it.

“Technology” itself derives from the ancient Greek teknologia, meaning the communication or, literally, word (logia) of an art or craft (tekno). Which might explain why Stonehenge’s “primitive” technology of stone still speaks to us and strikes so deeply, as if in a lost first tongue: No matter how “wired” we get, its art and craft remains immediate and eloquent.

Perhaps more than ever, Stonehenge manifests an architecture of sky and light, the motions of moon and sun, human bones and desire to be healed, mineral permanence and ephemeral season, a circle for song and gathering. Left to stand for 5,100 years, it’s become a technology of human meaning, to be In Search Of: What becomes as time imprints our minds and bodies each moonrise and sunset and solstice, each illness and funeral and birth, each story and hope and theory about this singular transformative setting. Stonehenge holds it all in place, vast shards of our root genius: the ceaseless capacity for measuring, creating, and marvelous noticing. •

Graphics by Emily Anderson. Original images courtesy of Wikimedia commons.