Shagga glowered, a fearsome sight to see. “Shagga son of Dolf likes this not. Shagga will go with the boyman, and if the boyman lies, Shagga will chop off his manhood.”

No, that’s not a parody of A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin; it is A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin. And if I begin my discussion of what is in some respects a remarkable creative achievement with a sample of bad prose, that’s because A Game of Thrones is virtually an encyclopedia of bad prose. It has bad exposition, bad dialogue, bad sex scenes, bad nature description, even bad free indirect discourse, to use the term for the narrative device Martin employs to advance the plot while taking us inside the heads of his principal characters.

You don’t have to wait long for the clichés to collect. They start piling up in the second paragraph, precisely 19 words into the book: “’Do the dead frighten you?’ Ser Waymar Royce asked with just the hint of a smile.” That’s just the hint of a cliché. Others practically scream at you: “Her loins still ached from the urgency of his lovemaking.” “Prince Joffrey’s mount was a blood bay courser, swift as the wind, and he rode it with reckless abandon.” “Her eyes burned, green fire in the dusk, like the lioness that was her sigil.” Hackneyed language is so much the norm in A Game of Thrones that Martin’s occasionally happy coinages in the manner of Anglo-Saxon compounding, such as “sellsword” for mercenary or “holdfast” for fortress, light up the page like – what should I say? – the green fire from a lioness’s eyes burning in the dusk.

The obvious objection to this objection is that most readers of the genre don’t expect or even want fantasy fiction to be especially well written. Fresh, energetic prose, a prose of nuance and implication, might only gum up the works. Clichés, after all, serve a purpose. They’re shorthand for what everyone already knows, and part of the appeal of fantasy novels is the familiarity of the ominous ravens and the towering battlements and all the other musty furniture with which they’re stuffed. Why avoid the clichés when the clichés are the most direct route to getting you where you really want to go – namely, to a castle on a remote crag where lords and ladies engage in courtly dialogue or, in the case of A Game of Thrones, to the palace of a capital city where the beautiful but treacherous queen contrives murderous plots and everyone else is likely to be mutilated, disemboweled, or decapitated at a moment’s notice?

It’s the hyper-violence rather than the courtly dialogue that most engages Martin’s imagination. He’s at his best when talking about “Valyrian steel” and what it does to human flesh. The perpetual violence or threat of violence that hangs over nearly every page evokes the more horrific aspects of the Middle Ages or Renaissance Florence or, more uncomfortably, our own less than fully civilized world. The violence destabilizes order and continuity; anything can happen, and does. Martin’s primary inspiration is the English War of the Roses, but the institutionalized savagery in the courts of Josef Stalin or Saddam Hussein seems just as pertinent. The term “fantasy fiction” inadequately describes A Game of Thrones.

Apart from the dragons and the giant direwolves and that sort of thing, nearly everything in it has, so to speak, already happened. Richard III really did have his pre-adolescent nephews murdered in the Tower of London, as the highborn Jaime Lannister casually murders (or thinks he murders) the inconveniently observant eight-year-old son of the rival Stark dynasty. The victims of Josef Stalin’s show trials confessed to wholly imaginary crimes, as Lord Eddard Stark confesses to uncommitted acts of treason at his show trial in a vain attempt to protect the surviving members of his family. The young, capable, and charismatic Henry VIII and Mao Zedong turned into bloated tyrants, as does King Robert Baratheon, whose death by wild boar attack recalls a similarly symbolic emasculation in the myth of Adonis. And if the psychopathic boy-king Joffrey seems too baroque for credibility, he’s easily outclassed by the Emperor Caligula or Idi Amin or Kim Jong-il or any number of criminally insane despots who have darkened our world.

In his lumbering way, Martin seems to have vast tracts of history and mythology at his fingertips. (He certainly has Shakespeare ready to hand. I know of no work of literature more informed by the somewhat tedious Henry VI tetralogy.) Not that he lets his erudition get in the way of his storytelling. The legions of Martin’s fans probably aren’t looking for parallels to the Biblical Exodus (which occur in the chapters dealing with the disinherited princess Daenerys Targaryen, who leads her followers across a waste not unlike that of the Sinai Peninsula in quest of the promised land of her ancestors). They’re looking for heroism and horror and magic and treachery and sexiness and ultra-violence, and they find them. I believe the technical term for this is “trash.” But if this indiscriminate mixing of modes, this compulsion to be ceaselessly entertaining at any cost, this utter lack of self-consciousness and irony defines the genre that Martin works in, he shares some of these traits, at least in part, with authors like Charles Dickens or, if we may speak of the racier parts of the Old Testament, God. None of this is news. Great writers have always drawn on popular formulas and folkloric conventions. They just, you know, write better.

Even so, the delirious energy and liberating tastelessness of A Game of Thrones can’t quite encompass what more reflective works of fiction readily accomplish. If you’ve spent your life reading people like Leo Tolstoy or Zadie Smith, you may find transitioning to A Game of Thrones a bit of a challenge. The resourcefulness of literary language, the representation of heightened consciousness, the complexity of an engaged author/reader relationship – these things have no place in the work of George R. R. Martin. I myself, typically uniformed in such matters, probably wouldn’t have got around to A Game of Thrones if I hadn’t first read about it in the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books. Daniel Mendelsohn and John Lanchester had shrewd things to say in those journals about Martin’s insistent feminism and his handling of genre conventions; more importantly, they reassured me that I need not hide my copy in a drawer.

My copy, not my copies. A Game of Thrones is only the first of (so far) five published novels, each about a thousand pages, in the series that Martin has titled A Song of Ice and Fire. Unlike Mendelsohn and Lanchester and every Martin fan I’ve met, I have scant desire to read beyond the introductory novel. I’m sure I’m missing some wonderful stuff. For example, the geographic breadth of Martin’s imagined worlds, the polarities of wintry austerity and summer rot, the sense that nature will always have the last word – all this, I can only assume, gathers strength as the series progresses. Similarly, the vision of political power as entirely meaningless except to the aristocratic gangsters who covet it and the common people who get chewed up in the process – well, I don’t know exactly where that’s going to go. I guess I’ll have to watch the television version to find out. Hence the major advantage of the TV series over the books – although you miss much of the density, you get most of the plot without the deadening prose.

It’s the deadening prose, finally, that defeats me. Every time I read another “Robb shot back” or “Jon admitted stiffly” or “Ned muttered darkly,” I cringe a little. Even allowing for genre conventions that favor an undistinguished style, I can’t shake the thought that Martin’s effects would be more powerful if delivered with a modicum of expressiveness. And if the style is that crude, doesn’t that suggest that thought behind it might – just might – be a little lacking in substance or wit?

There’s a scene in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing in which the hyper-articulate protagonist Henry uses the example of a well-made cricket bat as a metaphor for the efficiency of carefully crafted writing. Hit with a proper bat, he explains, “the cricket ball will travel two hundred yards in four seconds, and all you’ve done is give it a knock like knocking the top off a bottle of stout.” Hit with an improper piece of equipment, “the ball will travel about ten feet and you will drop the bat shouting ‘Ouch!’” The real bat, Henry says, “isn’t better because someone says it’s better, or because there’s a conspiracy by the MCC to keep cudgels off the field. It’s better because it’s better.” Just so with A Game of Thrones. It would be better if it were better. •

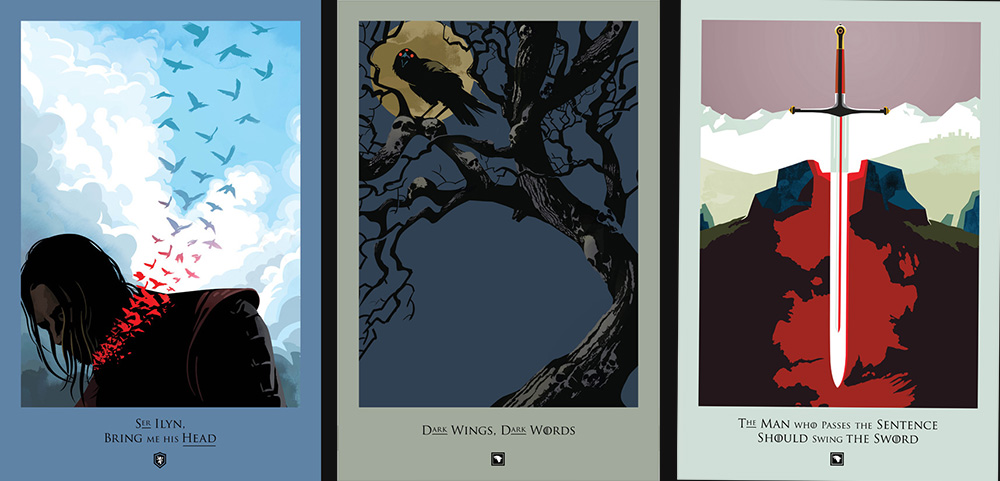

Feature image art by Melinda Lewis. Source images courtesy of Robert Ball via Flickr. Article photos courtesy of Duncan Hull, Fabio Barbato, Gage Skidmore, Kmeron, and Chris via Flickr (Creative Commons).