“Honey, there’s been a fire . . . ” My mother’s quiet voice on the other end of the line delivered the news without a tremor.

I stood in the middle of a concrete platform in downtown Tacoma, a city in Washington State I’d never intentionally visited. My family had always just driven past, breathing in that familiar paper-mill odor and singing, “Oh, the aroma of Tacoma.” That day, I’d wanted to visit on purpose. I had neglected the city, and it deserved some appreciation. The smell had vastly improved anyway, and there were pockets of Tacoma I truly enjoyed, especially around the marinas. I’ve heard you can sometimes see Orcas in the harbor, but I never got so lucky.

“What do you mean a fire?” I asked.

“Grandma’s house caught fire. She didn’t make it.”

“What?”

“They don’t know how it started. The police asked if she had any enemies. I told them she didn’t.”

It was raining in Tacoma, and my husband and I just stood in it — him probably wondering what I was talking to my mother about and me wondering how the hell my grandma was suddenly just gone. She hadn’t been sick. She wasn’t even in assisted living. “I need a drink,” I said to him after ending the call and explaining the situation. It felt wrong to just go on with my day like nothing was amiss when everything was extremely, overwhelmingly amiss. “How am I not crying right now?”

“It’ll sink in,” he assured me, but I don’t think it ever did, not the way it should have.

Just that summer, we’d visited her. Just that summer, I was in her little, yellow house, reminiscing with her about the pudding pops she always greeted us with on the back porch when I was a girl; of the nights I was so keen to sleep in her basement because I thought it was haunted and I adored ghosts; of hot, summer afternoons spent lying in her yard, feeling each blade of grass prick my skin like I’d found the most comfortable bed of nails. We’d lit off fireworks on her front walk — remember the ones that grew into long, ash worms? — while she made sloppy joes inside.

To me, Grandma was summer.

“Let’s find a bar and toast her,” my husband said. “That’ll be nice.”

“It’s something, anyway.”

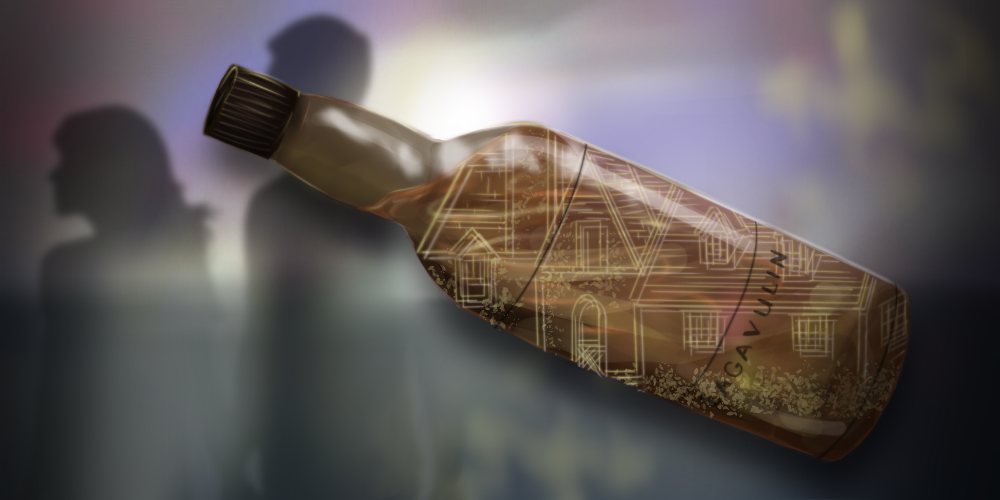

We found a lounge we would never have splurged on ordinarily. The word oyster appeared in the name; I remember that. The lounge is gone now. I know because we went looking for it after our dog died. To us, the place had become somewhere to go when somebody died, a ritual of sorts. I don’t do funerals. Apparently, what I do instead is Lagavulin 16.

The entire surface of that bar was covered in ice. My skin would stick to it a bit before the ice melted and let go again. I enjoyed the ambiance. Blue light glowed under the counter and created the illusion that the whole thing had been carved from ice. More blue light illuminated the shelves behind the bartender. It was a classy lounge for polar bears, I thought, polar bears and penguins.

“What’ll it be?” the bartender asked. My husband and I were not sophisticated drinkers, but we’d been introduced to Lagavulin 16 by a scotch-obsessed college friend of his. It’s all I knew that wasn’t the cheap stuff, so it’s what I ordered. “Are you sure?” the bartender asked. “You know that’s 14 bucks a shot.”

“It’s a special occasion,” I told him. “I’ll have a double.”

Here’s the thing about Lagavulin 16. It tastes like woodsmoke. It’s a bonfire in a glass with a touch of pipe tobacco. The flavor overwhelms your senses and dulls the rest of the world. It seemed particularly appropriate for Grandma’s toast.

These days, Lagavulin 16 is what I use to toast the life of a loved one who’s died. It stamps the moment in your memory, that flavor. It burns that death in your belly until smoke floats up your esophagus and into your mouth, and you can taste it lingering on your tongue, full of all the things you can’t even think to say.

We toasted her, and I remembered her, glad my husband had gotten to meet her once before she died. Yes, she’d had a stroke and behaved more like a spoiled child than a grandmother, but you could still get the gist of her. She was still there, buried under forgetfulness and odd tantrums. You could still see her strength and her stubborn independence.

After she’d yelled at him for something trivial, I told my husband about how my grandfather had left her with a half-empty closet and a scrawled note explaining that he’d run away with his young secretary to “find himself.” My grandma had to raise their three children on her own, and she did. Ironically, she took a job as a secretary to support them — a job she was eventually pushed out of when a younger, more attractive woman applied. That seemed to be a theme in her life. After her stroke, Grandma occasionally let some of that old anger slip out. It was never really meant for whomever she took it out on. It was just the injustice of years long past, the ghosts of her memories coming back to haunt all of us. Her house still smelled like summer to me on that last visit.

My mother told me that when she was going through what was left of Grandma’s house after the fire, the smell of smoke was overwhelming. She had to wear a mask and step outside from time to time. It made her sick, especially near the back porch where the fire had started. They told her Grandma was likely inside when it happened. She’d probably heard something on the porch and opened her back door to see what the ruckus was. And then the backdraft . . .

They said Grandma had probably run through her house, past her front door — why? — to her bathroom, and she passed out in there. She never woke up again. I can’t stop picturing it, that moment when she missed her chance to escape. She died later at the hospital. It was the smoke that killed her. They say it’s the smoke that kills most people who die in fires. The fire takes your attention, and the smoke takes your breath away.

My mother told me the smell of smoke was overwhelming, even in the hospital. She’d flown immediately to see Grandma after the fire. She’d been there when Grandma died, and what she can’t forget — there’s always something you can’t forget — was the smell of burnt hair. It was disgusting, nauseating. But she sat with Grandma anyway and sang to her and waited for her to let go.

The day my grandmother died, I sat at a bar made of ice with fire in my belly and smoke on my tongue and remembered her and the little, yellow house where she’d raised her children. I thought they would both stand forever, her and that house. They seemed so strong, so immovable, such a vital part of the landscape.

I should have known Grandma would take her house with her when she left. “I’m never going to sell this house,” she’d told us. “They’ll have to drag me out of it kicking and screaming.” She was so certain, and her often self-proclaimed optimism paid off in the end. She got what she wanted. No one else will own her house. They knocked its shell down when the investigation was over, but I know Grandma took it with her.

Maybe it will seem strange that her house isn’t sitting next to that big shop on the corner — what did they sell there anyway? — but I probably won’t go down that road again. Without her, that road doesn’t exist, that shop doesn’t exist, and the gravel alley behind her house just isn’t there anymore. She embodied all of it — Deadwood, the Black Hills, that one restaurant that serves the best prime rib in South Dakota, that park with the huge, fake dinosaurs, which I know are much smaller than I remember. Everything feels huge to a child. I’ve had so many dreams about secret, luxurious rooms hidden away in Grandma’s little house. My unconscious mind decided it was bigger on the inside, I guess.

The sound of her voice, too, is stamped in my memory — the skipping record of her full, exuberant laugh. She sang bass in choir and was so proud of her low range. As she aged, her voice developed a pleasant rasp; a smoker’s voice, they called it. She smoked right up until her dying day. She lied about quitting, and we just pretended to believe her.

At some point, we all decided it was a cigarette left in a flower pot with flammable potting soil that started the fire. The firefighters had suggested the cause, and we just accepted it. But we’ll never know for sure. Some mysteries are never solved. Still, my mother decided to quit smoking after the fire. She just couldn’t stand the smell of it anymore. It made her feel sick every time she lit up.

Grief hits everyone differently. To me, woodsmoke will always be the flavor of remembrance — a fire in my belly and ash on my tongue — just the lingering traces of a life that was bigger on the inside, like all of them are. We are so combustible. And we leave traces of ourselves behind, curling tendrils of the lives we lived, misremembered, romanticized, immortalized ghosts.•