About an hour west of my house is the Carlisle Barracks, where, from about 1879 to 1910 there existed something called the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. A boarding school designed to educate Native Americans, the school’s goal was to immerse its students in Western European culture, so they could fully integrate into American society.

To that end, its founder, Richard Henry Pratt, espoused a philosophy of “kill the Indian . . . and save the man.” Those enrolled in the school had to renounce their name, religion, and culture for the sake of integration. More than 10,000 American Indians were educated at the school from 50 different tribes and nations. Some were forced to attend. Others were sent by their families, hoping for a better life for their children. Olympic athlete Jim Thorpe, who was famously stripped of his medals, was a graduate of the school.

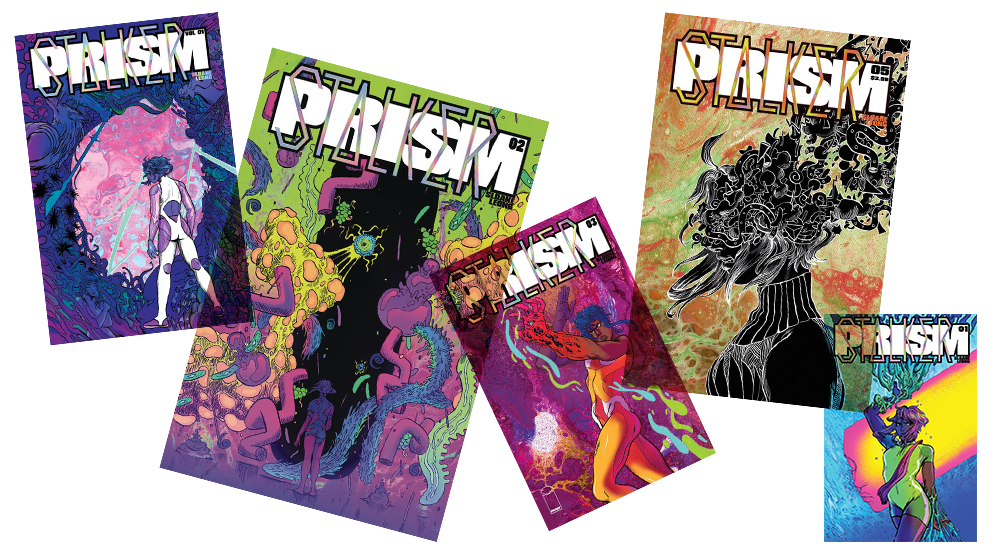

I thought a lot about the Carlisle Indian School, and Thorpe, while reading Prism Stalker a new, monthly series by cartoonist Sloane Leong, the first trade collection of which comes out in September. Although ostensibly a sci-fi series, Prism Stalker deals with issues of colonialism, imperialism, identity, and culture in a manner few comics in recent years — at least to my eyes — have attempted.

Prism Stalker focuses on Vep, a refugee from a planet ravaged by disease and taken in by “the Chorus,” a seemingly heterogeneous empire that spans the spaceways. As with most refugees, Vep and her family struggle to get by until she is given the “opportunity” (she doesn’t have much choice in the matter) to join the a newly formed “Chorus Academy” that will “help nurture settlements on a newly discovered planet.” Basically, it’s a version of the space marines, with Vep and the other new recruits being trained to help keep the indigenous population of the aforementioned planet in line.

Anyone who has watched a sports or military training movie (or read a shonen manga series) will be familiar with many of the beats Leong hits in the first few issues. To wit: Vep’s teachers are demanding and seemingly callous. Early attempts at kindness are met with hostility. Rivals seek to prove themselves by mocking her. The previously sheltered Vep feels lost at the school until she finally discovers her inner strength and ability. And so on.

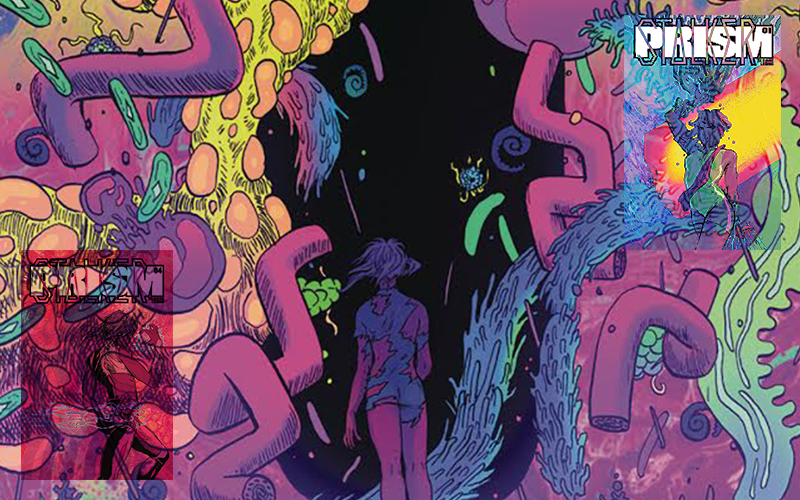

There are more sinister forces afoot as well. Asides are given to the hostile life forms on this odd colony, and suggestions are made that the planet itself might be sentient in some fashion. More experienced, battle-weary soldiers pop up from time to time experiencing a type of PTSD that involves hearing voices and having your skin turn crystalline.

But what I find most interesting are the ideas of imperialism, colonialism, and assimilation that Leong explores alongside Vep’s journey. One of the things that is emphasized from the get-go is that Vep has little to no memory of her original life, her native people, and their customs. She, for example, cannot speak their language. So when she meets a group of warriors from her tribe, she is immediately dismissed because “Our tribe has bad blood with yours.” “You’re something lost,” one of them snarls, “A poor rendition of your mother no doubt.”

What’s more, she is frequently discouraged from exploring or honoring her cultural legacy by the Chorus (“It is important for your social health to move beyond your base traditions”). When one instructor finds her wearing a family charm, she removes it, saying it’s “a distraction you can’t afford here.” Indeed, Vep is even denied the ability to say farewell to her family in person because “we don’t want to upset them.” And yet family is exactly why Vep and her classmates are going through this ordeal, to make their lives better. One of her classmates is clearly becoming ill from the crystal implanted in its body but refuses to to quit because “my cantatrix is relying on me.” Family is only useful as a way to make students sacrifice themselves for the Chorus. “Don’t disappoint the many depending on you,” a voice intones at the end of the first volume. “Don’t disappoint yourself.”

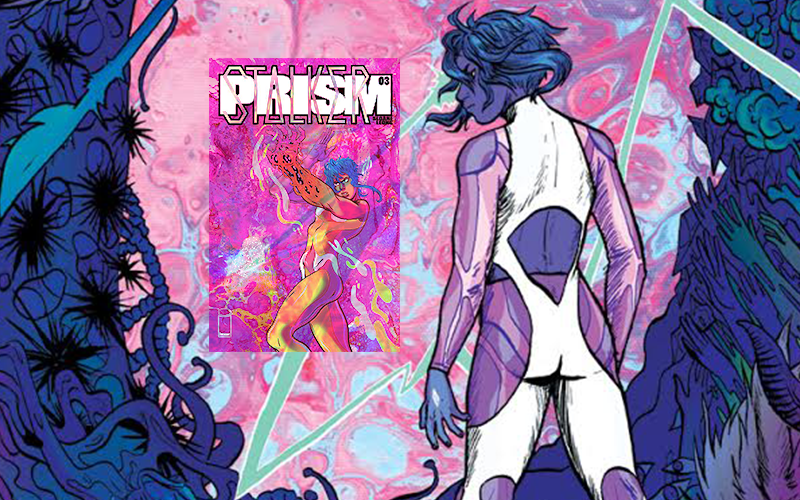

All this is delineated in a day-glo, psychedelic art style where things bend, twist, or ooze in all manner of permeable ways. Rather than study some space martial arts or high-tech armory, Vep’s training involves using imagination and willpower to bring her thoughts to reality as dangerous weapons. Or prevent something else from taking over her mind.

Leong also eschews Star Trek-styled starships and cityscapes in favor of more organic, fleshy structures. The various styles of architecture she inhabits resemble anthills or insect hives more than human buildings, and Leong does her best to ensure each character looks as strange and alien to Vep and the reader as possible. Characters are frequently enveloped by pink, purple and/or green goop. Vep’s head and body explode, fracture, and melt in a variety of ways throughout the comic, all calling back to the heady European sci-fi comics of the 1970s, best exemplified by the works of Moebius and Philippe Druillet.

I had to read Prism Stalker through more than once in order to fully grok its nuances. Though Leong clearly intends for readers to be disoriented at times by the strange alien world she’s created, there are moments where the trippy visuals, along with the formal and poetic dialogue (“Deny what you know in your bones and instill a new law of reality in them”), can make it difficult to fully understand who is who and what is going on. And while Vep spends a lot of time talking about how she needs to help her family, we’re given precious few scenes that establish that familial bond.

But these are small quibbles. In the end, Prism Stalker proves to be a comic that harkens back to the best of the heady days of ’70s sci-fi, where you come for the psychedelic visuals and stay for the allusions to contemporary issues. I wonder what Jim Thorpe would have made of it. •

All images courtesy of the author and collaged by Isabella Akhtarshenas.