Were you to ask me which reading experiences I treasure the most, I’d answer you by saying the ones that don’t stop. That is, they were first experienced by me at a given point in life, but they didn’t leave off there. I’d come to them again and again, while in different phases and modes of myself, and each encounter would be a kind of revisit and also a fresh readerly start.

It’s easy to cite massive, learned tomes that fill this bill. For instance, there is no iteration of myself or my moods, that does not take solace and find companionship in a couple of hours spent with Thoreau’s journals. If a reading experience can be a friend, I’d say those words with their dual citizenship of the Concord woods and the metaphysical world housed in the gut and soul of all of us are boon companions of mine.

At the close of what seems another impossibly hard week, I can repair to the café with my Thoreau — take a tonic of prose, as it were. I regroup, commiserate with the text, and ready myself to get moving again, finding the belief that the boulder can be crested over the top of the hill. The journals come with me as I go about my life because they’ve become a changing part of who I am, adapting like friends do to help us in our moments of need, which is sometimes simply a need to grow anew.

But if I have a best friend among texts, I would have to say it’s a series of Young Adult novels that are now not terribly well known, but remain beloved by those fortunate enough to have been introduced to them.

These would be the Three Investigators books, which were initially launched in 1964, the brainchild of Robert Arthur, Jr., who’d been thought of up until that point as a writer of speculative fiction. Arthur wrote scripts for the radio series The Mysterious Traveler, and also the TV show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, the latter surely playing a part in the genesis of his Three Investigators series.

The title characters were a trio of boys named Jupiter Jones, Pete Crenshaw, and Bob Andrews, who live in the fictional California town of Rocky Beach, not far from Hollywood, on the coast. The location was selected for max narrative flexibility and what I call atmosphere-ism, which is what you get in creatively creepy ventures like the early Universal horror pictures, the London of Jack the Ripper, and the moors of Victorian times. Ditto the fictional Rocky Beach. There are various brine-endued adventures atop cliffs and within crags and caves where the echo of the sea can sound like a bellowing dragon, and one’s potential escape speed on a Huffy is of paramount importance.

Thanks to a Jupiter Jones-led encounter (for Jupe is a master talker — what the English would call a blagger) with Alfred Hitchcock himself — all of this made up, of course — the penguin-shaped director serves as unofficial sponsor of the boys’ detective team, introducing their cases and getting them work. We’re never really sure how old the boys are, but they can’t drive, they’re in their teens, and the most athletic member of the group — Pete — can sometimes fend off a man, so let’s say they’re about 15.

I’ve always viewed the Three Investigator books as the cool YA series for those in the know. Everyone was aware of the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew, and I read all of those books, too, but I knew right from that first moment of discovery that the Three Investigators were for me.

They were my speed because they felt more interpersonal. The Hardy Boys, for instance, were rich. They had certain airs. They didn’t lord their privilege over anyone or anything like that, but certain people — and characters — have a way of making you feel immediately at home. And, more to the point, better at home with yourself. In my life, these people have often come in character form, and the first were the lads of Rocky Beach, who also taught me a massive amount about writing.

My first meeting with the Three Investigators was in fourth grade. We’d have to write these short stories, and I took this quite seriously. On the bus on the way to school, you’d not wish to come between me and my story-related thoughts. There I sat, thinking hard about what I’d compose. Would I feature a haunted house? An abduction? What about snakes? Could we do something with snakes?

I’d tear through the story I had to write, then busy myself with reading material as the other kids finished their respective potboilers. I read Jack London’s White Fang, a biography of Sandy Koufax, Dickens’s Oliver Twist, and then, one day, there was the beckoning cover of Arthur’s The Secret of Terror Castle, the first entry in the storied career of Rocky Beach’s finest deductive triumvirate, with an image of intrigue straight out of a horror picture crossed with a dash of Disney’s The Haunted Mansion ride. Two of the boys had just been rescued by the third member of the team, who had apparently brought help to the scene in the form of an adult who held a flashlight, though only an arm was visible. Already I asked myself, “Wait, are we to trust this adult with the torch?”

I was to learn that the rescuing boy was none other than Bob Andrews, the brainy, bespectacled member of the group whose dad worked as a Hollywood props and special effects man. Bob suffered a leg injury when he was younger, and had a slight limp. He’s humble of frame, but meticulous when it comes to details, which serves him well with his job at the Rocky Beach Library, and as the team’s research honcho, oftentimes dubbed “Records” by Jupe and Pete.

Pete Crenshaw is the team’s Second Investigator, a boy who has reservations and an unease around danger, but he’s fit and strong and he’s always willing to help out his mates.

Then we have Jupiter Jones, and I loved Jupe from the start. He’s an orphan. I didn’t know my own biological parents, and that meant something to me. Jupe is chubby and had quite a following at one point as a local television child actor dubbed Baby Fatso.

I cringe when I wonder if that detail would be struck from these books now, on account of “fat shaming,” because it would cut into the admiration that one has for these characters. They’re not hardscrabble, but they have no pretense. There’s little in the way of privilege and entitlement. There’s spit and vinegar and this prevailing feeling of three kids pulling themselves up by their collective bootstraps, their ingenuity, their bonds. And their honest-to-goodness, lived-in desire to help people. But also with an element of competitiveness and pride — pride in one’s ability, pride in doing a job that others could not. I dug this. And I’ve never stopped.

Jupe is the Sherlock Holmes figure of this ratiocination bunch. He’s enigmatic, well-read on everything, drops arcane “vocab” words — which are quite standard words, but hey, we’re a quasi-literate society — on his “fellows.”

They refer to each other that way, as in, “Quick, let’s get back to Headquarters, fellows!” Big all for one and one for all vibe. Jupe enjoys withholding information near the end of one of the team’s cases in order to create some additional drama with his theatrical “reveal.” If he had Dr. Watson as an uncle, the steadfast biographer of S. Holmes would have known what to expect and delighted in the junior version of big boy deduction.

Jupe lives with his Uncle Titus and Mathilda, who own a salvage yard. Think of Sanford and Son, with usable, useful junk everywhere, and it is in this yard, out of an abandoned trailer, that the boys build their Headquarters, which has all of these nifty secret tunnels leading in and out. They have all of their crime-solving equipment stashed inside what’s tantamount to a lab holed away in the coolest of all clubhouses.

There’s a periscope that looks out into the yard, and when I journeyed with the boys into this space, it changed me as someone who thought about stories in a particular way. I always wanted to know who did it, or if the ghost of the castle was, to use a phrase of Dylan’s, really real, though the prospects of supernatural agency tended to be explained away, with just enough of a fractional remainder to make you think, “hmmm, golly.”

But the unmasking of the latest baddie — and sometimes you were disappointed in who it was, as if they’d personally let you down, based upon other qualities they’d shown — wasn’t the real plot. The real plot, as I read these books, felt them, experienced them, and as I remember them, was in the relational. How characters interacted, how they served as mirrors unto each other. “Hanging out” — which, let’s be honest, is why everyone loves the duo of 221B so much — was the story because it doubles as the human drama. The textured richness that made “mere” plot something humanly reticular.

The ways in which we interact with each other tell stories. They tell, in my view, the most compelling stories which also impel us to revisit them the way one does an important exchange in the mind and memory. You can return again and again to a Three Investigators novel, in the same way you can with The Wizard of Oz, that first Star Wars film, or those Thoreau journals I mentioned. Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Think of that novella — you want, in all likelihood, for all of this tsk-tsk business to work out well for Scrooge, but what is pulling you in is how he interacts with the ghosts, and the shadows of his own life. It’s the relational. Not the plot, which is, at the same time, a humdinger, but the plot is in service to the relational.

I don’t think you could have taught me a bigger lesson about writing, voice, tone, connectivity between author and reader, and life than you could have by saying, “Here, young Colin, why don’t you check out this Three Investigators series?” There are no references to pop culture, so the characters exist in this kind of Perpetualland, which I imagine as a less denial-based realm than J.M. Barrie’s Neverland.

There are no cell phones, of course, no internet, but the boys do engineer what they call the Ghost-to-Ghost-Hookup, in which each member phones a few friends asking for info, and then request that those friends phone a group, and so on, until hot clues come rolling into Headquarters. They have a rival in Skinner (“Skinny”) Norris, who is jealous of the boys’ talent and enterprising spirit. He’s a rich kid, with his own set of flashy wheels. The boys themselves bum rides with Hans and Konrad, the two large-bodied Bavarian young men who work at the salvage yard, though they sometimes have their own Rolls Royce, complete with dapper chauffer — a young guy himself — in Worthington, on account of Jupe winning a contest prize.

Robert Arthur wrote the first nine books in the series, as well as the 11th, with William Arden stepping in for a baker’s dozen worth of entries. In all, there are 43 titles in the original run that was then followed up by a shorter series in which the boys are older, and Bob, of all people, is this sublime romancer of the ladies. Jupe, alas, can’t catch a break or land a date.

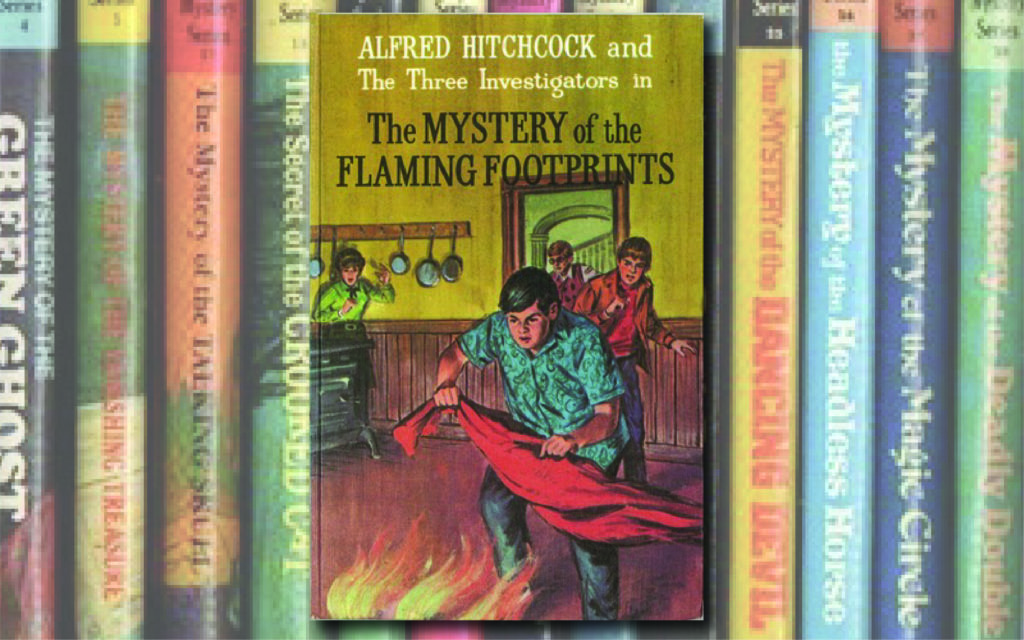

My favorite Three Investigators author is M.V. Carey, the initials standing for Mary Virginia. Born in 1925, she stepped into the series in 1971 with The Mystery of the Flaming Footprints. Her books lean harder on the horror, and she nails the tone — the rapport of these three friends. They’re each so different from each other, but in those differences, they locate strength, sublimate insecurity. There’s no envy for what the others can do for each of them — only opportunity to learn and grow.

I think probably the best book of all of the 43 is 1975’s The Mystery of the Invisible Dog, written by Carey. It possesses that degree of re-readability. The story unfolds over the Christmas break, after the holiday itself is done, and I’ve never known a work of fiction to capture that interregnum feeling — the inbetween time — of human life like this one.

For me, it was a work that helped instill early on that the shifts in life are never official, or at least rarely so. For life itself is lived in lacunae; gaps are, paradoxically, the substrate, and less the open spaces we think they are. The boys are bored, school hasn’t started up yet, the euphoria of Christmas has passed, but wreaths and decorations still hang, lights continue to twinkle. That mood of time and place in which setting becomes a character, infiltrates your readerly being. The book might as well open up and pull you in.

I’d stay up deep into the night reading these works, bargaining with myself to consume just another chapter, and before I knew it it was two in the morning. Or whatever it was. There was no time. That sensation is what a writer wants — that’s what you’re going for.

I read — or, rather, now I glance at — so much MFA-machined fiction drivel. Work that has no point to it, no guiding purpose, no connective tissue. I see fiction written as an exercise for the author to tell him or herself that this is their “thing,” what makes them special, gives them identity. But there is no value for the reader. There’s no concern for the reader, that wondrous entity I call “the person on the other side of the table.” The real writer exists only for that person. That person is everything. That person is the entire point. Not the writer’s ego, not so the writer can feel “oh look at me, ma, I’m good at something.” The writer is in service to that person on the other side of the table because the writer does not exist if they are not writing to reach that person. To include them. Not to talk down to them, to leave them behind, or as is so often the case, to use as a prop in order to show off, let loose the jargon, all but say, “You’re not as smart as I am.”

The Three Investigators book helped me realize that if you actually want to prove your intelligence, then move someone at the level of who they are with a story you created that they feel is also their own. That’s it. That’s also everything.

The books are self-contained, such that you can dip in anywhere, but they repay series loyalty. One of our great joys as readers, listeners, film watchers, is recognizing a reference to that which came prior. We give ourselves this sort of subconscious pat on the back that is warming.

What always impressed me is how the various writers of these mysteries must have read all of the other books in the series — done what today we call a deep dive. Carey’s tone is more flexible than the other writers, but they’re all within a few subtle shades of each other. The books don’t really age. I’ll dip into the Hardy Boys from time to time, but those tales read like excursions in nostalgia from a bygone era I never knew within the timeline of my actual life. Conversely, there’s an immediacy to the Three Investigators series and a level of writing that I’d put above anything you find in just about any major North American publication. That sounds like a joke. But I don’t know how many places I’ve ever written for — and I’ve written for a lot — where what we can call the median prose reaches the heights of these books.

The books helped me learn how to plot, to take risks in narrative. You can have plot points that seem outrageous, that become grounded and plausible when they’re rooted in the lives of the characters if those characters are sufficiently developed. The characters will dictate the story, even as parts of the story unfold outside of their necessarily circumscribed selves.

Learning these lessons as a young writer was akin to teaching me how to split a prose-based atom. I’ll reread the books now, to focus myself, to calm down if life’s events have induced terror or panic, but also to experience them as etudes — study pieces that double as reminders not to over-throw as a writer, to mix literary and sports analogies. The books, like the Investigators themselves, stay within themselves, locate their range and power there. From the inward, comes the outward. From the small comes the big. Those are the directions you always want to be going in as an author.

If you seek imagination in what you read, you’re rarely going to find it in today’s so-called literary fiction, where no emperors wear any clothes, and a lot of people in a twisted system seek to keep out anyone unlike themselves, lacking a similar background, schooling, cronies, agent, false friends, etc., and a turgid, lifeless prose style that no one on planet earth actually really cares about. Modern publishing is a class system. The Three Investigators represent a meritocracy as a series, and as budding detectives.

They always read “fresh,” and the nicest thing I can say about these books is perhaps the most important aim — or it should be, anyway — of anyone who has ever attempted to tell a story upon a page: you never feel, as the reader, like you are reading. You’re having a life experience instead. There are none of those concomitant groans that are triggered by books that trigger flashbacks to homework you despised doing because it was make-work, a slog when you would have done anything to trade it in for fresh air or a compelling narrative with dynamic characters. And there is absolutely zero mystery as to why that’s the end-all, be-all power that the very best writers seek to unmask and pull out into the light with a flourish that would do even Jupiter Jones proud.•