Back in the alleged halcyon days when you could actually make a living making comic books (but had to hide your profession from everyone for fear of censure), one of the titles used in an attempt to mollify the sneering intelligentsia and bourgeoisie was Classics Illustrated, a lengthy series that by and large set about adapting classic literature — Shakespeare, Poe, Hawthorne, etc. — in the most mundane and unimaginative way possible.

As the medium’s status has risen over the past decade and a half, these kinds of adaptations have made a comeback of sorts. And while they might not bear the official Classics Illustrated moniker, they are, with few exceptions, plodding affairs, displaying little in the way of intelligence, wit, or imagination. Looking over the bulk of them, you might well wonder whether there are any cartoonists capable of adapting prose in a manner that avoids mere rote recapitulation of the original text.

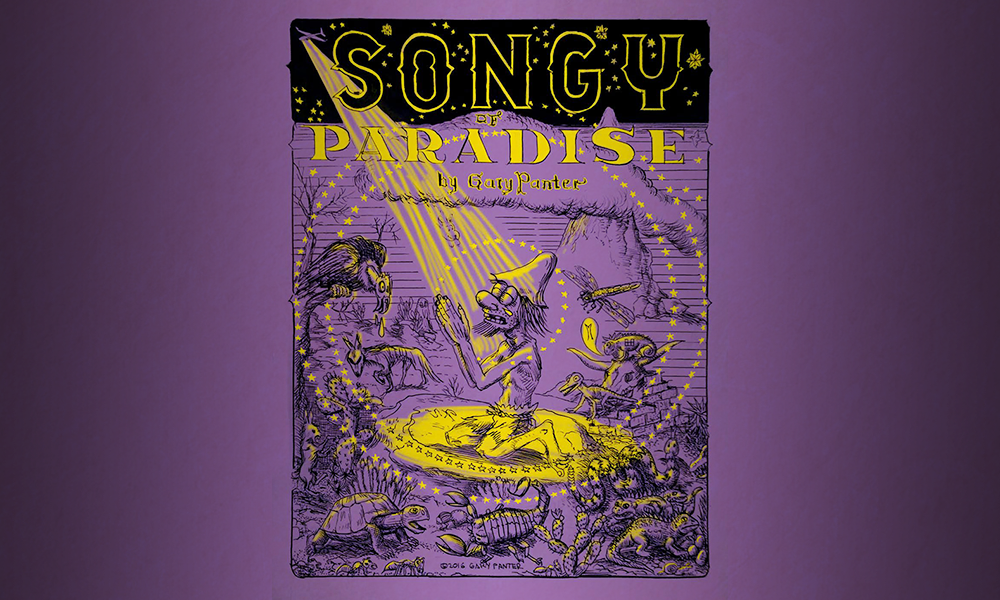

Which brings me to Gary Panter. Over the past two decades, while lesser lights were churning out uninspired versions of Romeo and Juliet or Pride and Prejudice, Panter produced two visionary (and rather large) books loosely based on Dante’s Inferno: Jimbo in Purgatory and Jimbo’s Inferno. Now, the pseudo-third book in the trilogy, Songy of Paradise, has arrived. It bears some marked differences from its predecessors, both in scope and source material, but in its own way is just as visionary and masterful as the previous books.

Panter came to prominence during the punk and new wave scene of the late 1970s and early ’80s. His roughhewn, kinetic art graced covers of seminal music fanzines like Slash and offered a visual accompaniment to the harsh, aggressive sounds coming out of New York City and L.A. He also — along with folks like Charles Burns, Kaz, and Mark Beyer — was part of the next generation of cartoonists that arose from the ashes of the ’60s underground. Their work, mainly seen in the anthology Raw, offered an edgier, more experimental aesthetic that picked up where the hippies left off. In addition to comics, he’s done painting, light shows, puppetry, sculpture, and more. He’s probably best known today, however, as being the set designer for Pee Wee’s Playhouse.

Eschewing Dante altogether, Songy of Paradise is an adaptation of John Milton’s Paradise Regained (“but without Milton’s verbosity,” Panter slyly notes on the title page). And whereas Panter had previously swapped out Dante for his own hapless wildman, Jimbo, in Inferno and Purgatory, here it’s the stalwart fence-post digger and hillbilly Songy taking the lead role.

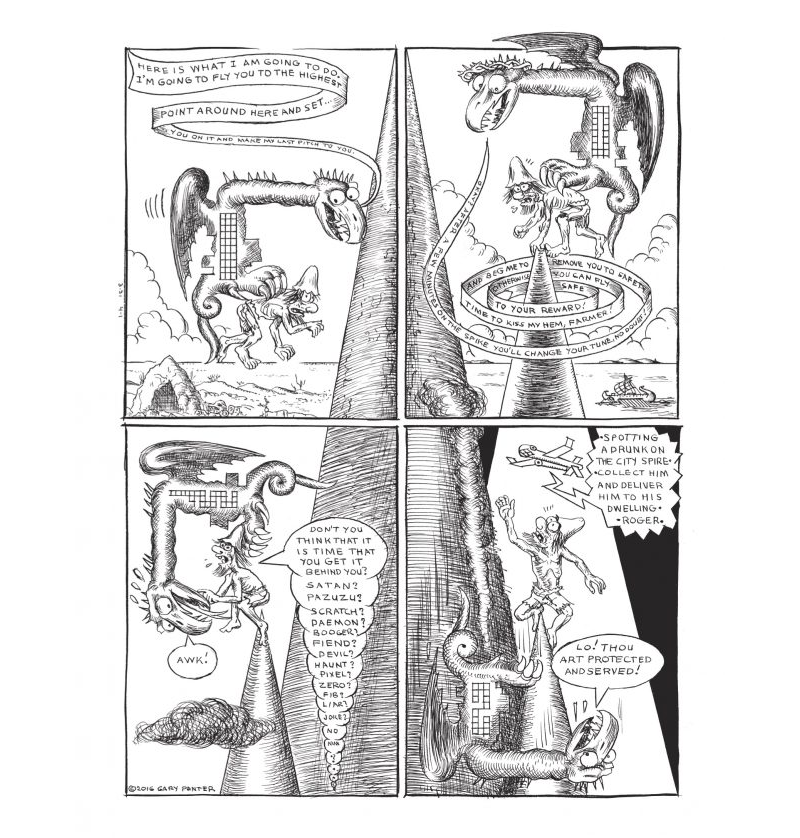

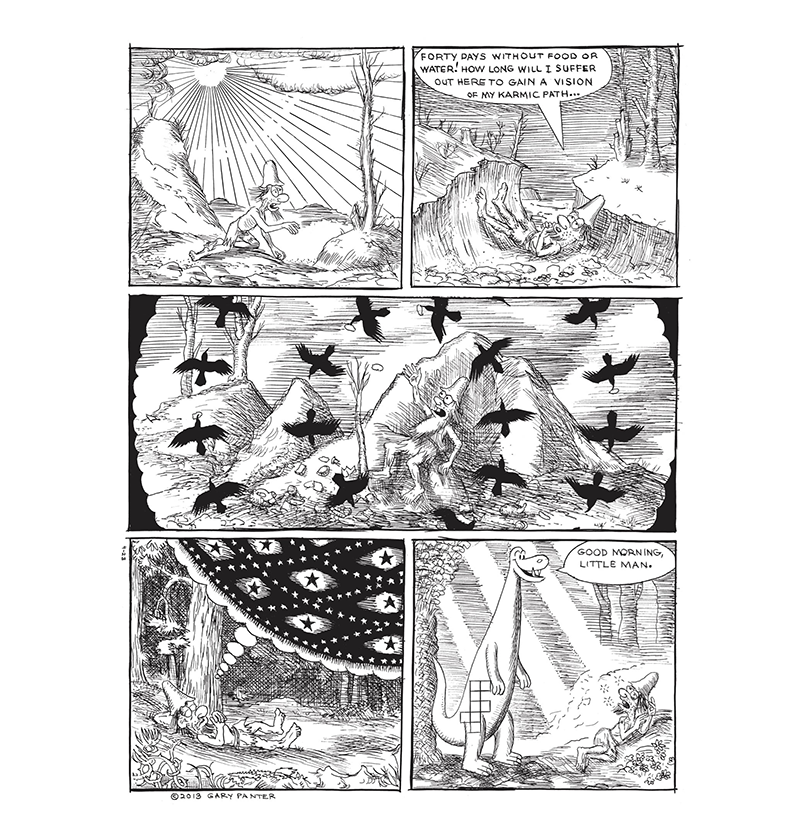

As with Milton’s poem, Songy of Paradise re-enacts the Biblical temptation of Christ. After being “baptized” by a friend (with a drone in place of the Holy Ghost gazing on in approval), Songy heads into the desert to undergo a “vision quest.” There he is greeted by Satan, who is angry that “the lords of might have taken close and special interest in a mere farmer.”

The devil then attempts to persuade Songy several times to abandon his fast, offering him wealth, food, power, and more in exchange for fealty and (perhaps) friendship. Songy, like his predecessor, however, is unmoved by Beelzebub’s coaxing, responding to Satan’s ornate, poetic dialogue with direct, and often quite funny, quips (“Seems to me like you are trying to sign me up for some macho trip.”).

Panter’s Purgatory and Inferno amalgamated his wide swath of influences and interests from traditional high and low culture into one thick cultural stew. Jimbo in Purgatory, for example, contains references to not just Dante, but also Boccaccio, Chaucer, Ovid, Aristotle, Raymond Chandler, Bruce Lee, Alice Cooper, Frank Zappa, the 1973 film Westworld, and god knows what else.

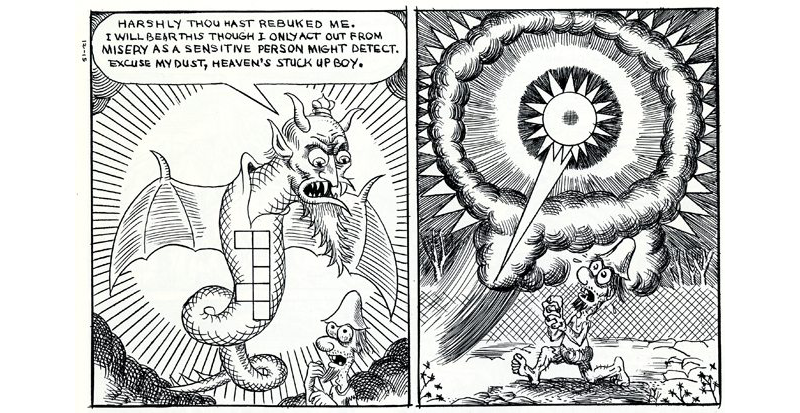

And while Songy of Paradise is Panter’s most straightforward and readable work in the trilogy, it does not lack in rich, offbeat references. Satan, for example, changes form throughout the book, first appearing as a dragon, then as a hunched old man. Later he is depicted as Syd Hoff’s Danny the Dinosaur and finally as the 1812 political cartoon of the “Gerry-Mander” monster.

There are also abundant references to non-Western art. Satan, for example, continually appears with a crossword-type design across his belly, which is apparently taken from a Javanese manuscript. Many of the demons and other figures appear to be taken from Japanese and Assyrian art. Honestly, Panter’s references are so rich, deep, and personal that it can be tough to keep up with him.

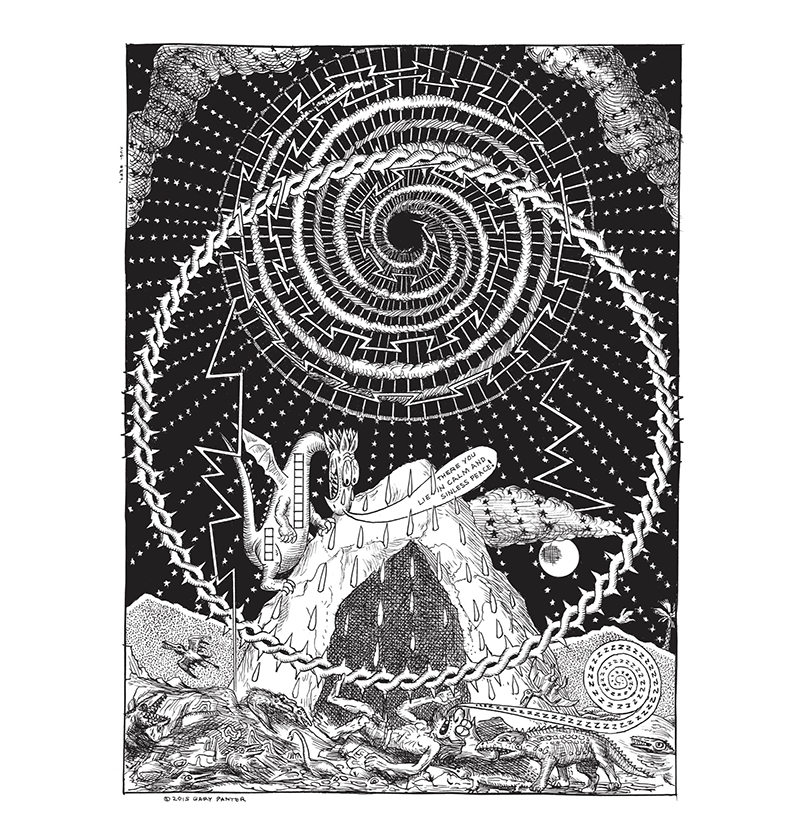

This is no simple game of “spot the reference,” though. In terms of craft alone, Songy of Paradise is a masterstroke, abounding with deceptively clever composition and stunning layouts. Whereas Purgatory, with its tight nine-panel grid and elaborate use of patterns, created a deliberately cramped, claustrophobic, and tightly controlled atmosphere, Paradise by contrast feels much more open and airy. He rarely adheres to anything more six panels per page and often employs a full-page illustration to convey Songy and the devil’s debates and visions.

And what visions! Panter fills these panels with elaborately detailed images of armies marching and battling, fallen empires, masses of tiny, militarized police racing to stop something, prehistoric animals, a Roman coliseum, and radiating concentric circles made up of stars, lightning, thorns, and more. Songy might be lighter and in some ways more conventional in structure than Purgatory, but it produces a sense of awe all the same.

A shallow, surface reading of the book would condemn Songy in Paradise as a mere send-up of Milton and Christianity with its contemporary allusions and swapping out Jesus for a dim-bulb hillbilly. But there’s more than that going on here. Beyond the “holy fool” archetype that Songy so clearly personifies, Panter (who was raised in the Church of Christ and describes himself as having been “traumatized by religion”) conveys both an interest and reverence for the mythos and emotion this Biblical story holds, if not the literal interpretation. Is Songy admirable in his refusal to hear Satan out or just a stubborn, ignorant jerk, denying the very nature of change itself? Is Satan a fearful, jealous tempter or a lonely pitiable figure all too aware of the transience of things? Both perspectives seem to be true at various points of this short book, and that push/pull dynamic makes for one of the best comics you’ll get to read this year. •

All images created by Gary Panter.