You’re not supposed to hitchhike in Nevada, but I figured it was the Fourth of July. When the cop asked what I was doing, I told him I was trying to see some art. He didn’t follow. Land Art, I said, giant earthworks impressed on the landscape. It was an idea that drove artists out of galleries in the ’60s and ’70s: the art of digging a hole and naming it, of moving rocks and salt, of framing the world. One Land Artist filled a field with lightning rods and invited the public to spend a night in a cabin among them. Another grew a wheat field in the then derelict Battery Park. There’s an apartment in SoHo filled with soil, by the same guy who built the Lightning Field. I used to visit the Earth Room once a month. But the Land Artist who speaks to me loudest, whose work fills me with awe, envy, and an essential incomprehension every time, is Michael Heizer. He dug Double Negative, his early masterpiece, into this desert, the Mojave, when he was around my age, in his early 20s. I waved out toward the sand, past the gas station, and looked into the cop’s inscrutable eyes.

You wouldn’t believe some of the stuff out here, I said.

His silence seemed to say it back.

When Heizier landed in Vegas in July of 1968, with friends Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt, almost 50 years earlier, the airport was a lot smaller. They stepped off the plane right into the desert. Holt’s first experience of its untempered vastness induced ecstatic insomnia that lasted two or three days. “The time the three of us spent together in 1968 seemed deeply significant, like we were spawning an astronomical change.” she’d tell art-critic James Meyer in 2007. “From then on, I saw the world differently. There was no going back.” They drove off in a rented white Ford pickup, raising clouds of dust. Over the next 28 days, they hit Death Valley, the Mojave, and a cabin by Mono Lake. It rained the day before they flew back to New York.

Smithson and Holt were both in their 30s. Heizier was 23. But he was an old 23. He’d lived in Mexico City, Paris, and Berkeley. His father was an archaeologist and ancient monuments were the backdrop of his childhood. When Heizer rolled into New York, about two years earlier, he was already beyond looking for influences. Despite being a decade younger than the other artists at Max’s Kansas City, he felt himself to be fully formed. But something in the Southwest shook him on that trip, that summer of ’68. His family was from Nevada, and he saw opportunities there, materials, and symbols that New York could never provide. In the year that followed the trip, he began work on Double Negative, the earth sculpture that would shift the artworld’s center of gravity.

Travel fueled Heizer’s monumental idea. In the lead up to Double Negative, he took up to 20 trips a year. He’d frame those trips, in an interview with curator Julia Brown, as a deliberate search for something to say: “I felt that to make an American statement, you should experience many parts of the country.” I wondered if he’d really gone travelling with that aim of finding a “statement,” or if, like me, he was just following that impulse to move, to see, to understand. As I hitchhiked through the desert, I wondered if I should be building monuments too. Monuments to what? Myself? Loneliness? Isolation?

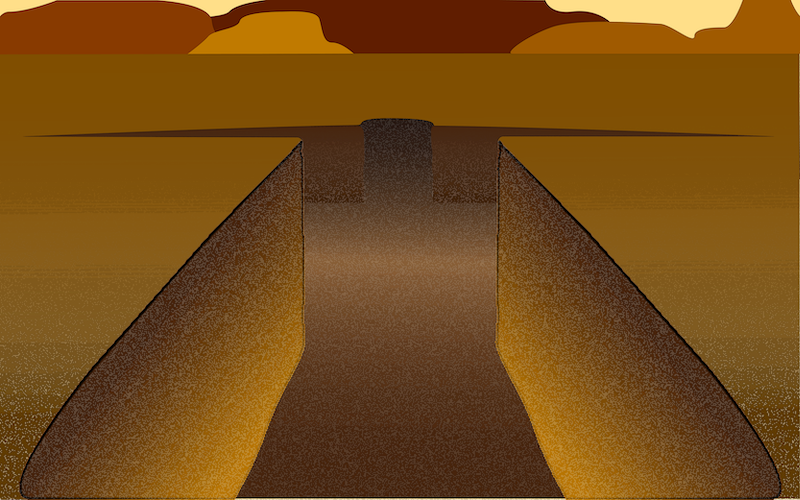

After he found Mormon Mesa, outside Overton, Nevada, Heizer started to dig. Unlike his father, he didn’t dig because of scholarly interest in ancient civilizations. He dug for the pure pleasure of it. “I like bad shit you dig big holes with,” he’d explain to Kara Vander Weg of Gagosian Gallery. About six days after he began, he stepped back and looked out on what he’d wrought. There were two perfect rectangles falling off into the chaotic middle, where the piece set aside its strict geometries and gave way to the natural curve of the mesa. It stood 1500 feet from end to end. Heizer laughed then. He laughed as though he stood outside time, laughed as if he was the first person to dig a hole.

At the gas station, I told the cop about Double Negative and the Land Artists that lured me into the heat. And he let me go on asking for rides. I couldn’t tell him exactly what had compelled me to see Double Negative, but one of the most satisfying things I can remember from being a kid is digging a series of ditches in the backyard with my brother. We dug a ditch through the sandbox, trying to dig a portal to China. We dug deep, past the crisp, yellow sand, down to the cold, dark New York dirt. Kept digging till one of us realized he was trapped and the other ran off to get a ladder. Another ditch was bigger. We dug it with our cousin and buried a chipmunk. After we put the dirt back, the grass grew only sporadically. We could still see the outline of our work.

•

On the day I arrived in Las Vegas, I got stuck in the desert, in 107-degree heat, trying to catch a ride to Double Negative. I sang Cotton-Eye Joe for two hours. My lips cracked. Whenever a new car would breach the horizon, I’d jump up and fling out my thumb. But it would pass, and I’d sit down again, suddenly exhausted. After all my jumping and singing, two Honduran fishermen stopped. They had four fishing rods each, jerry-rigged together for simultaneous use. As we drove, I watched the road roll on and wondered what I would’ve done if nobody had stopped. I’d have had to ration water until I could walk to Overton in the cool darkness. But these guys, with their ingenious two-man fishing-fleet, did stop, and I was grateful.

The next afternoon, I walked from Overton to Double Negative, past the little airport and the grazing cattle. I found a rare clump of shade on the slope ascending the mesa and crumpled into it. When the sun finally started to set, I walked the final five miles. That last stretch passed in darkness, forcing me to shine a weak light into the boulder-dotted expanse. I worked from memory putting up my tent. When my eyes adjusted, I saw light pollution breaking on the edge of the mesa. Heizer had taken his backhoe to the side farthest from the closest homes, but you could still see the lights propped in the night sky, still hear the buzz of life in the distance. The stars only became clear when I sat back, the tent up, my pack off. I drank a bottle of water in a gulp.

•

The morning light revealed how close I’d come to the edge of Double Negative in the darkness. A couple more steps and I’d have fallen 50 feet down. Overwhelming awe flushed any sense of fear. The monument is massive. Bigger than any description can convey or any picture or video can show. The consequence is unavoidable: The hole is very big and you are very small. Peering over its lip, I recalled a quote Heizer gave the New Yorker for a 2016 article. “It takes a very specific audience to like this stupid primordial shit I do.” Stupid and primordial, that’s me. “I like runic, Celtic, Druidic, cave painting, ancient, preliterate,” Heizer said, “from a time back when you were speaking to the lightning god, the ice god, and the cold-rainwater god.” I can’t help buying into these myths and legends. They tend to land me in American deserts, Uzbek mountain fortresses, and Burmese river towns. All of these places, where I’ve found a sense of connection to something bigger than myself.

Like its inspirations, Double Negative is a proper ruin now. The walls have lost their original sharp lines. Vegetation grows through its cracks. In his old age, Heizer has toyed with the idea of pouring concrete down the sides to restore his original vision. But the beauty of its crumbled state seems to have stayed his hand. The growing imperfections and fragilities only add to the mystery and power of the work. When hit by the right ray of sunlight, it breathes a life that other holes in the desert lack. You remember you’re far from the crowds and handy water fountains of city museums, far from home, alone. When the clouds shift and the sculpture lights up again, you start to think perhaps, just for this second, you’re in the right place, covered in the right layer of salt. You feel connected.

Packing away my tent, I looked up and saw a desert fox crawl out of the crevice. It walked along the edge and towards the center until it stood surrounded by the morning sun. I couldn’t possibly have been alone. An eighteen wheeler rolled past on the horizon trailed by a vortex of dust. I walked back to the main path and found a ride off the Mesa in a dune buggy. The driver must’ve thought I looked tired, dusty. The buggy shook violently as we hurtled down the side, wind rushing over the half-windshield. I held onto my hat and shouted, joy and terror, alienation and solidarity, “Holy shit! This is awesome!”

The driver laughed. He dropped me off at the next gas station. We congratulated each other on another Fourth of July. •