Was there any announcement in recent comics history that was met with more fanfare and excitement than the news last year that acclaimed author Ta-Nehisi Coates would be writing the adventures of Marvel superhero Black Panther?

It’s hard for me to think of anything comparable. Coates, of course, is perhaps the preeminent writer on race and American society today. His columns for The Atlantic have deservedly won him widespread praise and a MacArthur Genius grant. His second book, Between the World and Me, garnered him a National Book Award. He is one of the most prominent literary figures in the country. The news that someone of his stature would be writing the adventures of one of the most recognizable black superheroes (though perhaps Storm, Luke Cage, or Cyborg could argue for more cultural cachet) is worth a bit of hullabaloo.

And it came at a perfect time, as well. Comics — both in mainstream and small press circles — have been struggling with issues of representation and diversity for a while now. Just before the deal with Coates was announced, Marvel had unveiled a series of hip-hop themed variant covers, with various superheroes mimicking images from iconic hip-hop albums. Spider-Man and Deadpool paying homage Eric B and Rakim. The Avengers imitating the Roots’ Illadelphia Halflife. Dr. Strange copying Dr. Dre. And so on.

The problem was none of the artists drawing these comic book covers were African-American, which a number of people took issue with. Hiring Coates to write Panther is not just a great “get,” it gave Marvel the chance in the wake of that controversy to show that it does care about genuine diversity in the comics industry.

Five issues in (as of this writing), however, and — issues of representation aside — Black Panther is sadly a dull slog. Perhaps no comic could have lived up to the amount of hype that Panther and Coates received, but whatever expectations were unfairly laden at its feet, it remains a comic that — while far from inept or awful — is not particularly enjoyable or noteworthy.

The character Black Panther, a.k.a. T’Challa, first appeared in Fantastic Four #55 (by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby) in 1966. For all intents the first black superhero (there were a few predecessors), T’Challa is the king of a fictional, wealthy, and technologically advanced African country known as Wakanda. Though he has never perhaps attained the sort of instant recognition of a Captain America or Spider-Man, he remains a popular character and has had several praised runs in various comics (the most notable two being with writer Don McGregor in the 1970s and Christopher Priest in the ’90s).

All of which is to say that Black Panther is a well-established character with a lengthy and at times convoluted history, like most mainstream superheroes these days. There are two ways an author can take an established character like this. You can ignore all the backstory and start from a fresh, perhaps even idiosyncratic place (as Jonathan Lethem did when penning the underrated Omega the Unknown). Or you can embrace it wholeheartedly and not worry too much about indoctrinating new and unfamiliar readers.

Coates has clearly chosen the latter option. He’s not interested in reinventing the wheel or acclimating casual fans. An unabashed Marvel Comics devotee, Coates places his series well ensconced in the company’s current superhero universe utilizing as little hand-holding as possible. There are numerous references to past catastrophes that have befallen T’Challa, his family, and his country, but only cursory explanations as to what exactly those entailed — it’s assumed that everyone reading already knows this stuff. And if you’re not at all familiar with T’Challa and his environs, you’re going to get lost quickly.

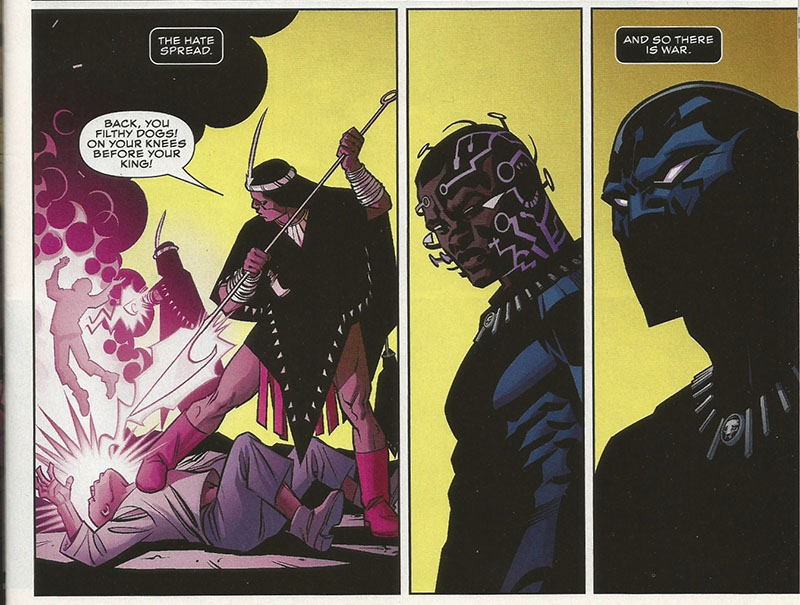

The plot involves Panther returning home to rule over a Wakanda that doesn’t necessarily want him there. Angry at him for palling around with his fellow superheroes instead of governing and still recovering from various cataclysms, the populace is on the verge of revolt, abetted by homegrown terrorists — some superpowered — and a pair of former elite soldiers turned revolutionaries.

So far so good. It’s a compelling plot that neatly dovetails with various global and national issues going on at the moment. And it’s nice to see Coates incorporate older women and LGBT characters into the supporting cast that don’t fall to stereotypes. We still don’t see enough of that in superhero comics these days.

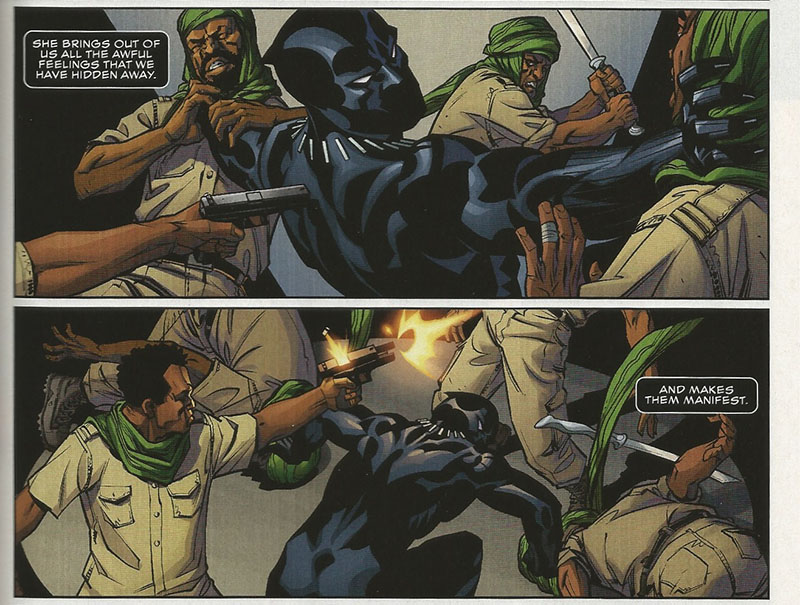

But Coates and artist Brian Stelfreeze (for the first four issues — Chris Sprouse takes on the art chores after that) avoid the direct storytelling approach whenever possible. Despite both the artists’ and writer’s considerable talents, Black Panther is often confusing and awkward in delivering basic plot points. I had to read the opening sequence — a fight between T’Challa, his soldiers, and some miners — a few times to fully understand what was going on or that the miners in question were being manipulated by someone in the crowd. An established villain is introduced later on with little fanfare or back story. Another villain reveals his powers during a key battle, but the revelation is framed awkwardly, in small panels, and again I had to reread the sequence to determine what was going on. While many critics accuse classic superhero comics of being too verbose and over-explanatory, far too much is assumed in Black Panther and not enough is flat-out stated.

At a more concrete level, however, I found it difficult to care about Panther and any of the other characters. Part of the problem is that everyone speaks in a high-falutin’, overly poetic language that comes off as far too stiff and earnest. I know to some degree that’s part and parcel of Panther’s style — he’s always been a relatively stoic character. Here, though, he’s so stoic as to be unsympathetic. It’s not just him though. Every figure broods and every word hangs heavy with import to the point where I desperately wanted some annoying comic relief sidekick to come in and sound off a quip or two.

Writing comics — especially if you’re working in collaboration with others — involves flexing a different set of muscles than Coates is probably used to here, something he’s no doubt aware of. It’s a heavily visual medium that has a rhythm and pacing (especially in superhero comics) markedly different from the sort of nonfiction prose he’s staked his reputation on. More longtime fans — those who have been traipsing into the comic shop every Wednesday for their Marvel fix — might get something out of this iteration of Black Panther, but I found reading the comic to be more akin to homework than entertainment. It’s entirely possible that Coates will eventually find his groove and develop a voice for T’Challa that resonates, but I don’t plan on sticking around any longer to find out. •

Images courtesy of the author and Marvel.