Wandering around Tokyo’s Shinjuku district alone one winter, on a research trip, I found a taco joint. No one who knows me was surprised by this. “Of course you found a taco joint,” my wife Rebekah said. “You always do.” I was raised in the Arizona desert, eating tacos, burritos, and enchiladas every week. Even though I’d moved to Portland, Oregon far from the Mexican border, I still ate Mexican food at a rapid, rabid pace. So when I found a hand-painted sign on the Tokyo street listing “Mexico tacos” and nothing more, I got excited. In Japanese tako means “octopus.” I loved grilled tako’s flavor, and I was curious to taste Japan’s version of my native desert cuisine.

My eyes traced the side of the building. Six stories rose overhead. It was an unusual building: a triangle wedged on a triangular plot on a busy corner, so that the building’s outermost tip came to a point, while the opposite end flared out, giving it the appearance of an enormous hunk of grey cheese. It was the sort of structure you might describe as an afterthought &smash; if Tokyo’s trapezoidal layout didn’t favor afterthoughts. Rather than leftover space, this was standard Tokyo efficiency. The tacos were not. Chain donburi automats like Matsuya, Sukiya, and Yoshinoya filled the city, alongside Yayoiken, CoCo Curry, and an abundance of udon, ramen, and sushi. These places filled my belly with succulent novelties and comforting carbs soaked in fat. The phrase “Mexico tacos” filled me with joy. Tacos. Somewhere in that building, tacos were cooking. I wasn’t even hungry, but I ducked inside the doorway anyway, searching for that familiar taste.

When I climbed the narrow staircase to the fourth floor, the restaurant was closed. I pressed my face to the window and peered inside. A small cook station overlooked a clutter of wooden tables. Cactus drawings decorated the signs amid Japanese characters. The place had an impressive selection of hot sauces. Colorful bottles lined the counter and cooking area, a shrine to the exotic flavors and brands of a region that people here fetishized in the way I fetishized Japan. With the lights off, though, the vacancy felt personal.

Disappointed, I stepped back into the stairwell and leaned my head out the window. For some reason, the window was open, even though it was winter. I looked out onto central Tokyo. Cars passed below. Pedestrians clutched cups of coffee in their gloved hands, and a cold winter wind blew through the trees in nearby Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden. High in the frigid stairwell, thousands of miles from home, I felt both invigorated and profoundly lonely. I left Japan two weeks later, having feasted on ramen, unagi, donburi, sanma, and endless bowls of nikujaga, yet never tasting a single bite of Japanese-Mexican food.

Weeks passed. I thought constantly of the people I’d met and places I’d seen. I went to work. The jetlag wore off. I told my travel stories to anyone who would listen, told them so many times that even I become tired of hearing them, though I never tired of reliving the events in my mind. Over time, the three, hundred-gram bags of sweet Kagoshima sencha that I bought dwindled to green flecks. “When it’s gone,” I told Rebekah, “I seriously might cry.” I used tube after tube of the Breath Palette toothpastes I bought from Tokyu Hands department store, starting with the Darjeeling tea flavor and working through the matcha, honey, and pumpkin pudding. And I made significant dents in the bottles of Hakushu whisky and Suntory Old Whisky that I packed in my carry-on luggage. I missed Japan, and my longing had me consuming anything that reminded me of it. All the flavors left me scheming ways to return.

I’d made a few friends there, like Daisuke. In that narrow ten-seat bar in Shinjuku, we traded laughs and stories, shared raw pig intestine sashimi, and he gave me my first taste of umeboshi shochu. Now we sent each other emails and photos to keep in touch. He sent photos of him and his friend Hide drinking. He sent photos of his daughter, and I sent photos of Rebekah and I hiking, walking our dog, and dressed up as Kurt and Courtney Cobain for Halloween. Talk regularly turned to food. One day I mentioned tacos and sent him a picture of me eating some carne asada. Had he eaten tacos in Michigan? “I love tacos,” he said. “But, I only knew tacobell and some of the Mexican restaurant in Michigan. (I know tacobell is not so good one hahahaahaa)” I offered to send him a recipe.

“The whole world must taste them,” I said, dramatically, “just like the whole world must taste 肉じゃが.”

“I surprised you use letter of Japanese in your email,” Daisuke said. “It is coooooool. LOL”

Food reminds me of people, and I see reminders all over my city: stylish white-guy ramen restaurants; donburi food carts; inexpensive sushi-go-rounds. I knew I’d get back to Japan someday. For now, I had to keep the memory alive. I had to muster the patience.

That’s when the idea came to me: open a food cart in downtown Kyoto that sells authentic Mexican food. Why just visit Japan, I figured, when I could live there? It was brash, impractical and never going to happen. But the seed was planted: There was an enormous, untapped economic and cultural opportunity to serve authentic, delicious Mexican food in an enchanting place that had little of it. There were crazier ideas — not that I was pursuing those either, but it felt good knowing I wasn’t the craziest of the crazy. There was some logic to it. In the midst of handmade onigiri vendors, donburi chains, and unagi restaurants, why not sell street tacos? Kyoto stands every imaginable thing side by side: quiet wooden temples and jam-packed Starbucks; mochi confectionaries and French patisseries; Buddhist shrines and love hotels; a department store and a hojicha roaster. The rich, smoky scent of enchiladas would weave seamlessly with the scent of grilled unagi. Kyoto life wasn’t defined by opposites so much as the harmonious interplay between diverse elements. My menu would be simple: just two types of tacos (carne asada and al pastor), two types of enchiladas (cheese and beef), refried beans, Spanish rice (even though I never eat it), bean and cheese burritos, and homemade horchata, with or without matcha. That’s it. Most conveyor belt sushi joints had canisters of matcha on the counter for people to prepare themselves, and my shop would of the same. And of course, it would have a sampling of sauces: green jalapeño, red guajillo, and pico de gallo. I liked to picture what it would look like. I’d be selling food from one of the street stalls the Japanese call a yatai, getting to know regular customers over time, getting to know the regular smells and sounds and beat of Kyoto’s daily routine, and eventually I’d invite certain regular customers over to my apartment to share dinner and listen to music, maybe sing and play guitar, all while bowing as I handed food over my cart’s narrow counter and our fingers brushed against each other. The problem was, I’d never open that restaurant. I couldn’t manage a business, and my life was firmly established in Oregon.

In lieu of a restaurant, I dreamed up something equally impractical: a magazine for Japanese people who dig Mexican food and have limited access to it. Named Taco Wagon after the iconic lonchero lunch truck and Dick Dale’s 1964 instrumental surf song, the magazine would combine elements of a cookbook, guide book, art book, and zine to celebrate food from northern Mexico, southern California and the American Southwest, what people call Sonora- and California-style Mexican food. This I could create from home. Whether people loved tacos and burritos and wanted to cook them themselves, or they’d only heard about them and wanted to know more, this magazine would be for them. It would be small. It would be colorful. It would be interactive and easy to use. When you weren’t carrying it around or using it in the kitchen, you could put it on your shelf with your books. And if you spilled sauce on the cover, the paper would be treated with a glossy coating so you could wipe it off.

Taco Wagon would be written in Japanese. And it would be a single annual issue, more a book than a zine, though it would have a zine’s dimensions — about the size of a DMV study manual — and a book’s production qualities. The debut issue would contain brief sections outlining what I’d call “The Basics” (ie, five pillars of Sonoran style cooking), ten simple recipes from famous restaurants; a feature called “Taco Origami” where perforated paper lets readers create a fold-up taco and fold-up burrito, to practice the art of folding the real thing; an illustrated map of must-eat Mexican restaurants in the US; a history of the lonchero; a glossary of useful terms (verde, rojo, arroz, polo); a short opinion piece called “What Taco Bell Does Wrong: Everything” (providing the sort of guide I wish I had for Japanese restaurant chains); a photo essay of popular hot sauces (including Cholula, Valentina, Tapatío, El Pato, Búfalo Chipotle Mexican Hot Sauce); and a hand-drawn anatomy of a tortilla press (drawn like a cartoon blue print, except with brown ink on tan paper). The issue would also contain a short personal essay I wrote called “Confessions of a Burrito Monomaniac.” Hopefully there was a Japanese word for “monomaniac.” If it was feasible financially, it would include a scratch and sniff page for beans and enchilada sauce, which would be pretty damn cool in any language. When readers weren’t carrying it around town in their bags or using it in their kitchen, they could display Taco Wagon on their bookshelf with their magazines and novels.

Taco Wagon would be a labor of love. All magazines are. That’s why most of them close after a few issues. But for me, the subject was personal. I loved the Japanese people and their culture. I loved Mexican food. I thought the world should taste the basic dishes that were so common in California and the American Southwest, just like I believed everyone should taste sanma shioyaki and nikujaga. The people I met during my time in Japan extended such warmth and hospitality that I wanted to return the favor. I also selfishly wanted a way to transport myself back to Japan in my mind, since I couldn’t afford to return yet in reality, and a magazine that sucked all my time and attention would do just that. Even when we shared few words in common, many strangers became friends over plates of fish and vegetables. Sometimes I failed to get the names or email addresses of the kind strangers I met at bars and cafes, but the Facebook friend requests piled up when I did exchange names, and I would remember those other people forever. I wanted to offer this magazine as a way to share my gratitude with them and to make new friends. Food, like music, is the great uniter, a universal language that connects all people despite our differences. In our era of war, xenophobia, and misunderstanding, we needed more sharing, cross-culturation, and compassion, and we needed reminders that we were more alike than different. Taco Wagon wasn’t meant to impose my way of life on anyone or dilute Japan’s unique culture. It was meant as an exchange. People shared with me. Now I wanted to share with them. And who doesn’t love to eat? Even when we lacked a common language, we would always have food, music, and laughter.

My other hope was that Taco Wagon would inspire some dinner parties. Maybe it would inspire people in Osaka, Kyoto, and further afield to start their own taquerias. The recipes would aim to help people do both. Although I hoped readers would enjoy cooking the dishes in each issue, I wanted to encourage people to go further: take the recipes and modify them. Add their own twist ─ some nori, some matcha, maybe dashi or miso — and transform them into something uniquely Japanese. Substitute shishito peppers for jalapeño peppers in pico de gallo. Use yuzu juice in place of lime, shiso in place of cilantro, adzuki instead of pinto beans. Use their imagination and the ingredients at hand. (Do you think iwashi tacos with spicy guacamole would taste good? I do.) Substitutions can be creative opportunities rather than deficiencies. When readers invented something delicious, I’d invite them to email and tell me. I wanted to taste their creations and share them on the magazine’s website.

We live in a global age. “Mexican food” is the vague umbrella term we use for food originally cooked in different parts of Mexico, which is an enormous, diverse country not unlike India. But when you’re eating it in Japan, as told by a white guy/gaijin/gringo who grew up in Arizona, cultural distinctions mattered less. Although I valued tradition, I hoped people would feel less bound to it with Taco Wagon in their kitchen, and that, like Osaka itself, they’d feel free to experiment and imagine new possibilities. (This is the process that helped Dylan Ho birth the now famous Korean taco in Los Angeles in 2007, which launched the West Coast’s roving food cart revolution. Naturally, alcohol was involved, too.) Meaning: Do your own thing.

Few of the friends I made during my three weeks in Japan had tasted Mexican food. Daisuke was the exception. What was interesting, though, was Japan’s appreciation of the culture of the West Coast and American desert. Many Japanese urbanites loved the West Coast, loved street styles and street fashion, loved LA and Mexican culture and the desert West. I met a guy in Shimokitazawa whose entire store was dedicated to Mexican art and the American desert. And the market for Portland anything and any small boutique items or food from Oregon was huge right now. Taco Wagon would mix all those elements.

When I pictured this zine for sale, I pictured it in shops of various types in Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto: independent boutiques like those that thrive in central Kyoto and Tokyo’s coolest neighborhood, Shimokitazawa; chain clothing and lifestyle stores like Beams and Journal Standard; in Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku; in the busy department stores like Tokyu Hands, Takashimaya, and the stylish Isetan; magazine stands in Shinjuku Station, and, of course, Uniqlo. Coffee shops and cafes would also be essential outlets. Many of those stores carry a cool selection of books, mooks, and magazines, and something unique from Oregon would probably sell well there. Back in Portland, there was this awful, white-washed, twee lifestyle magazine called Kinfolk. Kinfolk sold image and fantasy, but it sold really well. As their head of business operations, Doug Bischoff, said in an interview in the magazine: “But in Japan, Kinfolk has gone gangbusters. There, the culture’s abiding fascinations with natural-lit photography and intimate gatherings fueled sales so encouraging — 14,000 copies for the ninth issue — that Kinfolk launched a Japanese-language edition last June. ‘We were selling like crazy for the first two years,’ Bischoff notes, ‘and nobody could even read the text.’” That got me thinking. Anything was possible.

To produce Taco Wagon, I would have to tap my network of translators, designers, and illustrators, and I’d edit the text myself. Because I didn’t know the printing and distribution world so well, I figured I’d contact some established, independent food magazines to see if they be interested in working together on this as a one-off extension of their magazine, or at least imparting some wisdom. I’d design the thing, give them a mock-up. They’d print and distribute it. I’d create a list of shops to sell in directly, or sell through consignment by hand. I’d even fly to Osaka and Kyoto on my own dime to create a list, talk to owners, and pitch the thing. What would people you think? Sounds crazy? Yes. But good crazy, crazy good.

Just as Americans couldn’t spend their lives thinking teriyaki chicken and rubbery grocery store sushi were Japan’s main culinary exports, I couldn’t let Daisuke spend the rest of his life thinking Taco Bell was as close as he could get to Mexican food. “Bell” rhymed with “hell” for a reason. No more shoveling that stuff in your mouth, Daisuke. Time to get some smoky, slow-cooked enchilada sauce on your plate and raise our glasses to all the good times to come. I wanted all Japanese people to be able to cook themselves authentic Mexican food at all times, to circle the taco wagons, as it were, and feast.

I never created that first issue. Instead, I wrote this to make sense of my passion and my passing delusion. It’s a pale replacement, but Taco Wagon was a dream, and dreams are often more satisfying to hold on to than to realize.

•

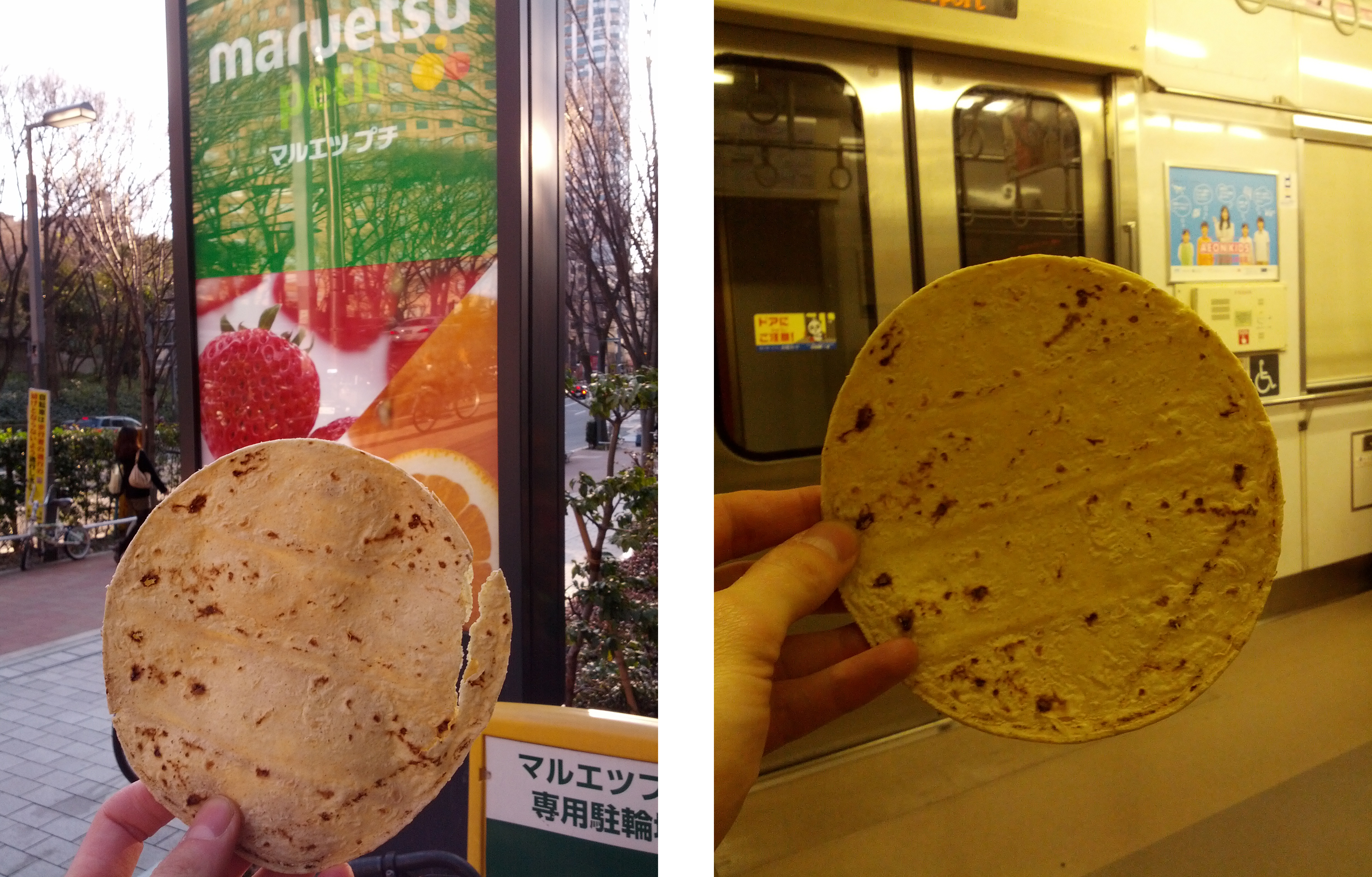

There’s still one Tokyo travel story I haven’t gotten sick of telling. I took a bunch of snacks on the 11-hour flight to Narita, including nuts, chocolate, and a stack of grilled corn tortillas. I’d eaten most of them by the time we landed, but as the subway from Narita raced through the suburbs toward Tokyo proper, I discovered one last tortilla in my backpack. It was wrapped in torn aluminum foil and beat up from the plane ride, but it was mostly intact. I wondered if a corn tortilla had ever traveled on a Tokyo subway before, or at least on this particular subway line. Probably not. There was no reason for that. So during a brief lull when passengers had cleared out, I held up the tortilla and photographed it. Raised to eye level, the yellow circle filled the frame. My wrist rose up from the bottom, its scars and veins familiar to my eyes, unlike any of the Japanese subway signs or ads that formed the novel backdrop behind it. This tortilla was commuting in Tokyo, I thought, just like me. This was how little bits of one culture infiltrated and diffused throughout other people’s cultures, until the mixture created a world culture. It all started like this.

As I positioned the tortilla to get it into focus, a passenger at the end of the subway car glanced at me, trying to figure out what weird thing I was doing without betraying her curiosity. Two intoxicated men in mechanic’s uniforms chattered nearby and laughed, clearly at me. I grinned and ignored them, and right then I hatched a plan: I would keep the tortilla for the next week so I could photograph it on a different subway. I’d create a series called Tokyo Tortilla, a record of its adventures riding the rails in the world’s largest city. Each day when I explored a new neighborhood, I’d photograph the tortilla on the subway that took me there. Day one: the Fukutoshin Line to Shibuya. Day two: the Yamanote to Ikebukuro. Day five: Hibiya to Ueno. Day nine: the Shinkansen to Kyoto. I could lay them all out in a sequence, glued together with brief text, or maybe on a map of the subway system. Like Taco Wagon, that never happened.

The next morning, I dropped my bag too hard and crushed the tortilla between some books, and when I pulled it out on the Yamanote line, it fell apart in my hand. The winter air had dried it out. It didn’t stand a chance. I still like to imagine how people would have received that series had I completed it, just as I like to imagine that this was the first corn tortilla to ever ride the Tokyo subway in from Narita. But I have strange dumb fantasies, most centered around Japan and Mexican food, and my imagination might have certain myopic limitations. There was already a taco shop in Shinjuku, after all, and surely its pantry was filled with tortillas. •

Images courtesy of the author, Joan Nova, Mike Mozart, James, erik forsberg, Indrek Torilo, and Herman Saksono via Flickr (Creative Commons)