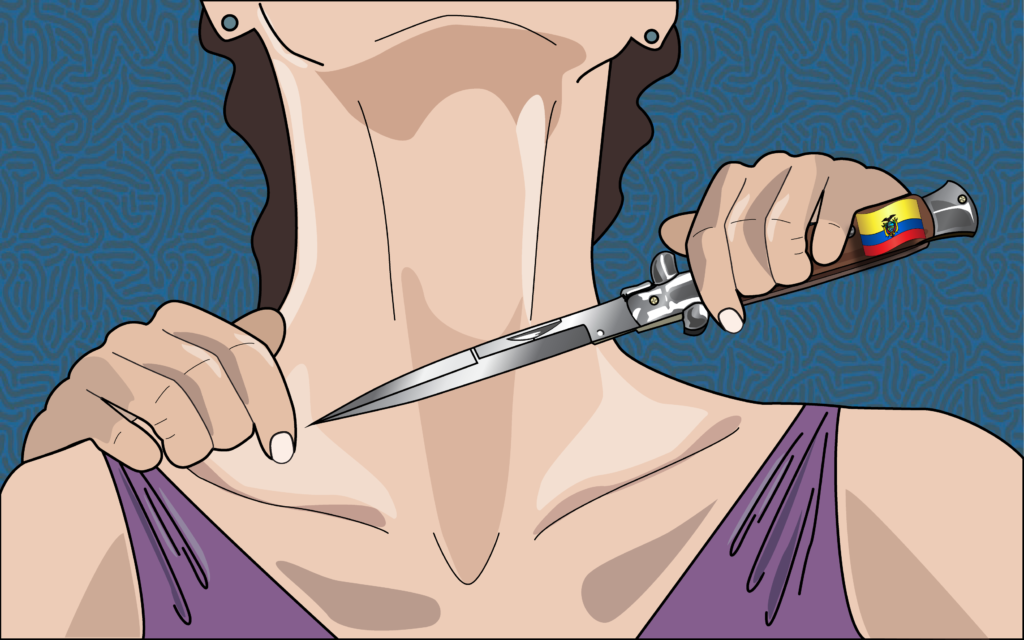

All of the hurt you’ve been hiding away

Cuts me at once like a switchblade

And take every stab you can take

And I’ll give it to ya, give it to ya

from “Switchblade” by LP

This is an essay about a mugging that happened almost 20 years ago, of a switchblade, pressed to a young woman’s throat in the dead of night. But this is not an essay about trauma.

On the night in question, I am in downtown Quito, Ecuador at the apartment of a man I’m casually dating — I’ll call him W. I remember the details of his second-floor walk-up — chocolate sheets on a single bed, albums lined up in milk crates — more than I remember the details of his face. We cook pasta and make out to reggae music before his deejay shift at a nearby club. When he has to leave, I say I’m too tired to go along, I’ll just sleep until he gets off work. But soon I’m restless. It’s hot and the bed is not mine. So, I change my mind. I leave W.’s apartment and walk toward the club because — why not? I have work tomorrow, but I also have coffee and a flagrant disregard for consequences.

The sky is black and the sidewalks are deserted except for a distant figure on the other side of the street, standing against a wall. A sex worker, I think. She waves at me with an odd enthusiasm and I wave back. If I detect any menace in the night, I don’t allow myself to acknowledge it. Nothing bad can happen to me.

I arrive at the club where W. is deejaying and, once there, the music lifts me. I sip at the watered-down cocktails I buy with wrinkled cash — I never accept a free drink from a man. I greet some acquaintances — their Spanish harder for me to understand over the throb of bass. Mostly I dance. When a track reaches the top of its frenzy, I throw my head back and forth and my hair roils around the contours of my face. I always forget how sore this will make my neck in the morning. I dance, buy another drink, whisper in W.’s ear on the deejay stand. He isn’t getting off anytime soon. These clubs go on all night, which is terrible for someone like me who hates to miss out. But I will have to drag children through English grammar tomorrow, and so I decide to walk back to his apartment and try sleeping again.

I take the same route, the fastest route, and in my memory, the woman from before appears like in a horror film jump take — over there and then suddenly over here, on my side of the street, and I’m sensing something’s off about the way her body moves, the proportions, and I walk faster but so does she. She asks for money and I say sorry, still smiling, still trying to be the kind of person who doesn’t automatically assume she’s up to no good, but then she is reaching for the wallet tucked in my pocket, so I reach for it too, telling her no, no, no, no and we both pull, but she is strong. Stronger than I am. Stronger than I would expect most women to be.

Because I am focused on my wallet tug-of-war, I don’t notice the others springing from the shadows until they’ve surrounded me. One of them holds a switchblade against my throat and says the words “Voy a matarte,” and I let go of the wallet and say “Tómalo” and “Dejame, por favor,” and this is where I am lucky: a taxi rolls down the empty street and the driver sees us, yelling out his window for them to let me go, and boom, I am thrown to the sidewalk like trash, and they are racing off, running away fast. I stand, speechless and basically unscathed.

When this happened, I was 22 and just out of college, living in Ecuador and teaching English because I wanted a life of adventure. I adore my young self for her snarling confidence, walking footloose through international cities in the middle of the night, and I shake my head at her recklessness. Part of it was the hubris of whiteness — something I would begin to understand only years later — and part of it was my silly pride in not being the Ugly American. But mostly my practiced nonchalance was born from a refusal to curtail any aspect of my life on account of my female body. Women are always told to be careful, and instead of fighting the reasons for that warning, I just fought the warning itself.

This story is the story of the night I brushed against a switchblade, but it was not a unique set of circumstances for me. For over a decade I shrugged off caution, riding solo on chicken buses and walking alone in the dark literally anywhere in the world I happened to be — before this night and after it. This is not an essay about how I learned my lesson.

The morning after the switchblade, once I got back home to my roommate and for a long time afterward, I told the story in a way that drew out the climax, using present-tense to punch up the drama. A girl alone in the dark, the glint of a switchblade, a sudden escape from potential tragedy: it became part of my repertoire.

Over the years, the story’s emphasis changed as the narrator did. In graduate school, I played the story for laughs. Because, at the time I lived there, the Lonely Planet guide to Ecuador contained a brief warning about tourist robberies in downtown Quito perpetrated by a “transvestite gang.” This had actually been a joke among my American friends in Ecuador because the idea seemed so preposterous — a marauding transvestite gang? Were the Lonely Planet writers having fun? Or just idiots? This says a lot about us back then — that we couldn’t imagine a real and complex underground hidden beneath the surface where we roamed.

The anecdote, as I told it in my mid-20s, relied on the absurdity of a man dressed in high heels as a robber with a switchblade. Ha, ha! Just picture it, this version implied. And in fact, I thought this story was self-deprecating, the joke on me: There they were in pearls. Right in the place the guide book warned they would be.

•

I spent more time living abroad and educating myself, and I became aware of the problematic aspects of this version. The story shifted again. Now, in the retelling, I was the Ugly American. I began to mention my Ecuadorian friend, the middle-class son of a government functionary, who refused to take public transportation to the parts of Quito where we went to party because he said it wasn’t “safe” to walk through those areas after dark. And how I had scoffed at the wasted expense of a taxi, feeling morally superior because I wasn’t afraid of “bad” neighborhoods, as if residents would see my presence on their streets as some act of social justice. I never considered the disregard this showed for my Ecuadorian friend, for his lived experience as a Quiteño, nor did I consider the fact that residing in a place for a year does not make one an honorary native.

How ridiculous it had been of me to think I belonged in my adopted homes of Chile, Ecuador, Nigeria.

•

Time passed and I became a writing professor at a small liberal arts university. I no longer told the story of the switchblade, but I still thought about it. But now, when I scrolled through the events, the part of the story I found most interesting was what happens after the muggers throw me to the ground. Because that’s when I do something bonkers: I get into the cab at the invitation of the driver, and we go barreling through the streets looking for the gang. Searching for them in the shadows. I am a vigilante hero and my mind an icy blade of vengeance. The windows to the cab are down, the streets silent except for the moments when we pass a bar or club and a sliver of music escapes, a flash of neon in the street puddles.

“The alley. We’ll try the alley next,” says the driver.

“Yes,” I say. “Rats love the alley.” Though surely not. Surely I didn’t say that.

Why did we take on this gonzo mission in the first place? I didn’t need the wallet, for god’s sake. All it contained was the equivalent of ten dollars and a worn photocopy of my passport. What did we plan to do, jump them back? I was certainly not in my right mind, but the driver — what could he have possibly been thinking?

We didn’t find them. He eventually took me home for free.

•

Like with any survival narrative, alternate endings always lurk in the shadows: The switchblade warm against my throat, I heard them say they were going to kill me. In another story, this is the scene where I end up dead. Throat slit. No witnesses. Or maybe it was all a bluff, and they would have thrown me to the ground and run off whether or not the taxi happened to drive by at that particular moment. I mean, who wants the attention of a brutally murdered foreign girl on a street corner near one’s turf? This ambiguity makes it hard to know: Did I almost die? Or did I just experience the most common crime perpetrated against tourists all over the world?

•

I have a bag of phrases I trot out each semester in my classes because I believe them: To be human is to be a storyteller, I say. Stories, both real and imagined, are how we make sense of our lives and, if you don’t tell your story, nobody else will.

But while I believe in the power of stories, I recognize the artificiality of them, too. The way we anticipate the audience. The way we maneuver obstacles and shape plot arcs, the way we develop characters to hold epiphanies and derive meaning from chaos.

In fiction, no matter how many plot dramatics a story contains, the power lies in how those outside events affect the protagonist’s inside story, their sense of self. That’s what makes an ending feel satisfying. The story of the switchblade was a textbook case of a life-altering event, and yet I was never able to articulate how this mugging affected me: no nightmares, no noticeable adjustments in behavior, no obvious experiences that would now be labeled as triggering. This is life, and the inside story is not stable.

•

So, though I no longer told the story, I still wondered: Why didn’t this event change me?

Maybe it was the alcohol: Did drinking too much (as I did so often in those days) blunt the emotional impact?

Maybe it was the Spanish: Does being mugged in your second language add another layer of psychological distance?

Or my family’s long-standing survival mechanism: Make another to-do list and check things off until you feel better.

Or the times: A (welcome) increase in mainstream dialogue surrounding mental health means that trauma-talk is now ubiquitous. But back then, we were expected not to be traumatized and so we weren’t.

My political worldview: Was I so intent on proving that girls could do anything boys could do that I never allowed myself to admit to the vulnerability?

The telling: Did the story itself slowly heal me? Externalize the fear? Help me take control of the narrative?

Or maybe it did change me: Like a parasite that hides in the body for years, maybe the moment affected me in ways too subtle or sprawling to isolate. Maybe this is an essay about trauma?

•

In June of 2017, I was at a karaoke bar, wildly pregnant and singing “Love is a Battlefield” with all the sober gusto my unwieldy body would allow. At home, I fell into sleep and woke in a puddle. The teacher in our birthing class claimed that, while in movies labor arrives with the drama of the water breaking, in real life, it almost never happens that way. For me it did, and six weeks too early. Soon, my partner and I were at the hospital, where I gave birth in a crowded room — at least ten doctors and nurses and the NICU team, all ready with their equipment to whisk away the baby as soon as the umbilical cord was cut.

Babies usually put on a cozy layer of protective fat in the last month of pregnancy, but my daughter was robbed of those weeks in the womb, and so she was not only tiny, four and a half pounds, but her skin drooped from her bones, her brow wrinkled and furrowed like that of an old man. For the weeks she was in the NICU, I struggled to pick her up from the plastic warming bed without disrupting the web of tubes and sensors connected to seemingly every part of her fragile body. I would strip off my shirt behind the curtain and hold her to my chest — kangaroo care, they called it — and think: You should still be inside of me. How can I protect you out here? People who came for the obligatory new baby visits looked alarmed, often too afraid to hold her, and my partner cried in the aisles of the third grocery store that didn’t stock preemie-sized diapers.

It would have made sense for death awareness to arrive with the switchblade — alone at night in a city far away from home — but instead, it came in the sterile first-world hospital of an expensive city while receiving the best care possible. For the first time in my life, the crushing anxiety of trauma overtook me, my body on such constant high alert that I literally didn’t sleep for weeks and later had to be briefly hospitalized myself, the staff shoving adult coloring books in front of me as my milk leaked onto everything, teenage depressives staring with wide eyes at the growing saucer stains on my shirt.

On one of the many sleepless mornings where I pushed my newborn daughter around the neighborhood in her stroller, we passed a poetry board hung with Mary Oliver’s famous poem “The Summer Day,” where the speaker asks, “Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon? Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

•

Now my daughter is a healthy toddler, a spitfire on the playground; now, there’s the dramatic irony of me, of all people, scurrying behind her saying, “Be careful! Know where your body is in space!” I want to teach her to do things differently. Don’t I? To take more care? Of course, we all want that. From time immemorial, parents have tried to warn their offspring, just as my parents tried to warn me. And from time immemorial, young people have ignored them.

Maybe this is a delayed coming-of-age story. A story about how, at age 38, I finally came to understand the fragility of life. A story about how you can go a long time without accepting this fact, but how when you do, it changes everything. You finally see the glint of the switchblade, not just at your own throat, but at the throat of everyone you love, every minute of every day for the rest of your one, precious fucking life. •