I stand too close to the edges of curbs. Sometimes, I stand so absent-mindedly and perilously close that a slight nudge, misplaced step, or strong gust of wind could lean me into traffic. The “whoosh” and hot air of a passing vehicle startles me out of my carelessness. Yes yes

Yes

Yes

That’s also when my Uncle Clarence’s voice pulls me back.

Yes

Yes

Clarence Thompson was the oldest of my mother’s siblings. I grew up in the same house in which they were raised, on San Antonio’s East Side. During my first 12 years, he was still living there and was the most constant male presence in my life.

In his room were boxes of books and stacks of vinyl records through which I’d rummage. It was an excavation of heritage and a discovery of voices that still enriches me.

Among the treasures found were collections of poems by Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes; Manchild in the Promised Land by Claude Brown; and James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, a small Dell paperback with its striking cover of Baldwin’s name in yellow letters and the title in orange set against a black background.

It would be a few years before I’d read, understand, and make those books part of me. But some of the records I found in those boxes in Uncle Clarence’s room, records belonging to him and my mother, I played within minutes and quickly fell in love with them. Albums like The Temptations’ Greatest Hits and Aretha Franklin’s This Girl’s in Love with You and Lady Soul, which featured “Ain’t No Way.”

In that time of discovery of new and unfamiliar voices, there were only two songs I played more than “Ain’t No Way,” and those were from a pair of Sam Cooke 45s: “Sugar Dumpling” with its B-side of “Bridge of Tears” and “Baby, Baby, Baby,” which was the B-side of “Send Me Some Lovin’.”

Cooke had been dead a few years when I found his records in the late 1960s with the famous RCA Victor label of the dog listening to the gramophone. Something about his voice — its raspy soulfulness, his phrasing, his confidence in his magnificent gift, and the clear joy he felt in using it — drew me in and made me, at nine or ten years old, probably the youngest Sam Cooke fan in my neighborhood.

Those voices from pages and vinyl would awaken in me senses of identity and pride.

A sense of awareness.

Uncle Clarence was a slim, elegant, and eloquent man who carried himself with such a naturally aristocratic air that a family friend called him “Sir Clarence.”

His voice was also shaded in aristocratic colors with crisp enunciation and a tone and meter I would later recognize as similar to James Baldwin’s. (Uncle Clarence went to Baldwin’s funeral at St. John’s Cathedral in 1987 and sent me the funeral program.) It was a calm, beautifully modulated voice that, with two exceptions, I never heard raised in anger or excitement.

The first time was on a very early morning in June of 1968. My uncle was a registered nurse who worked a night shift and didn’t get home until after midnight. On this morning, he hadn’t been home long when he broke the sleepy silence by stomping through the house, yelling, “I knew he should have kept his ass out of California! I knew he should have kept his ass out of California!”

The news had broken on television that Bobby Kennedy had been shot after winning the California democratic presidential primary.

Uncle Clarence was a passionate liberal Democrat who loved the Kennedys. He ran for the Texas state legislature in 1958 and four years later earned a mention in Jet magazine for becoming the first “Negro” chairman of the Bexar County Young Democrats.

He would stay interested in politics for the rest of his life but would never be as active after 1968.

The one other instance I heard him raise his voice in excitement was around that same time. He and I were walking downtown and came to a Walk/Don’t Walk light at the corner of East Commerce Street and Alamo Plaza in front of Joskes’ Department Store.

He was holding my hand, but I wasn’t paying attention to the Don’t Walk signal and was stepping off the curb into the street when he said “Child!” and pulled me back on the curb just as a car was turning into where I would have stepped.

I don’t remember what or if he said anything else afterwards, but I know that to this day, when I foolishly stand too close to a curb, I hear his voice saying “Child!”, and it pulls me back and focuses my attention.

Uncle Clarence moved to New York in 1972 and would return home for visits each summer and Christmas. The last time we saw him was the summer of 1991. By Christmas of that year, he’d been diagnosed with lung cancer and his doctor had advised against travel.

In May of 1992, my grandmother, not having heard from him in a couple of weeks, called his Bleecker Street apartment. Someone from the coroner’s office answered the phone and that was how my grandmother learned that her eldest child had been dead for a week in his apartment before anyone noticed. He was 56. My grandmother died two years later.

Two months after Uncle Clarence died, the Democratic National Convention opened on July 13, 1992, my grandmother’s 80th birthday.

On this day, she’d receive no flowers from him and no phone call at night wishing her happy birthday.

She reflected on the coincidence that in the year of his death, the city which he’d fallen in love with and moved to 20 years ago was hosting the national convention of the party to which he’d been devoted. Were he alive, he’d have been there, listening to speeches of some of his favorite politicians: Mario Cuomo, Jesse Jackson, Ann Richards, Bill Bradley, Barbara Jordan.

And the Kennedys.

He’d have loved the speeches by Teddy and Joe and the film tribute to Bobby , whose shooting sent him screaming into our house’s morning darkness.

My mother still lives in that house where we were raised. What was Uncle Clarence’s room is now a storeroom of sorts. Recently, I was cleaning it out when I came across a box of dusty vinyl records.

Flipping through them wasn’t the same as more than 40 years earlier when I was being introduced to unfamiliar artists and music.

A few of the albums were among those I’d seen long ago, but most of these records were bought by my brother and me while in our teens and 20s. This was a Sunday afternoon re-acquaintance with familiar, favored, and some forgotten performers. These were records seen and played before.

Except for one.

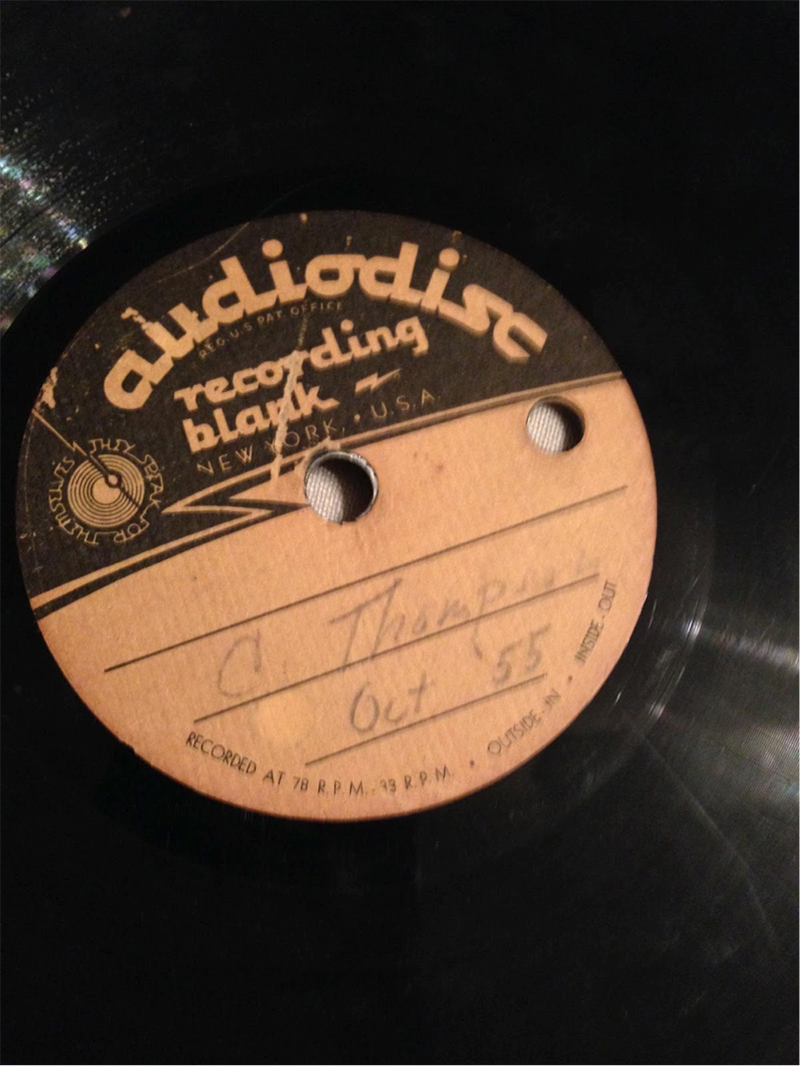

Hidden among the albums, a little smaller than the LPs, was a record with a cream-colored label identifying itself as an audio disc recording blank. On one side was hand written “C. Thompson Oct. 1955.” and on the other side was “C. Thompson May 1956.”

The record was older than me and had probably been among the stacks I first rummaged through as a child, but I don’t remember seeing it before. I took it home that night and placed it carefully on the turntable.

Side one of the record was chipped. The interplay of static and needle jumping each time around sounded like a jalopy chugging along in the rain on a bumpy road.

Static filled the room like an evening shower, and I waited for the drops of crackles and hisses to conjure a long-silenced voice.

Then, as summoned, arising from the grave and materializing from the mists, came the voice of my Uncle Clarence.

“Brothers, classmates, I am Clarence S. Thompson. I was born in Beaumont, Texas. I’ve lived most of my life in San Antonio. I have divided my school years between private and public schools. My father was a bill collector and real estate broker. However, he is no longer living. My mother is a housewife. I am a freshman majoring in pre-law at St. Mary’s University. I have one brother and two sisters.”

It was the first time I’d heard his voice in 24 years. Either technology or his not yet having grown into the full power of his voice made it sound a bit reedy, but it was unmistakable.

“At the end of this year, it is my intention to attend Yale University and to eventually attend Harvard Law School.”

Uncle Clarence was 19 years old and, presumably, practicing a speech he would give to a class at St. Mary’s University here in San Antonio. In 30 years, he’d attend my graduation from that same school. But he spoke on this recording while seeing the Ivy League in his immediate future.

He then proceeded to read from a speech by Adlai Stevenson, the 1952 and 1956 democratic nominee for president:

As citizens of this democracy, you are the rulers and the ruled, the lawgivers and the law-abiding, the beginning and the end. Democracy is a high privilege, but it is also a heavy responsibility whose shadow stalks, although you may never walk in the sun.

On side two, seven months later and in the presidential election year of 1956, Uncle Clarence practiced a speech urging his classmates to vote for Stevenson, calling him “the best and most capable candidate for President of the United States of America.”

He criticizes President Eisenhower’s “sloppy” slogan of peace and prosperity when “we have no peace in the Middle East and little prosperity in the Midwest.”

The record’s two sides totaled less than six minutes of Uncle Clarence’s voice, but that was nearly six minutes of hearing a voice I didn’t think I’d hear again. A few weeks after finding the disc, I played a recording of both sides for my mother, aunt, and uncle at a family gathering in Houston. As they listened to their brother’s voice, astonishment and fond remembrance mingled with sadness in their eyes.

The cliché is that the music of certain artists is the soundtrack of our lives. But the earliest, most encompassing, and more enduring score in our memory is the chorus of a cappella voices of family; voices when stilled by death won’t be forgotten, yet also won’t again be heard.

I imagine that relatives of public figures whose voices are preserved in the public domain are used to — if never unmoved — by sometimes hearing their loved ones’ voices transmitted in some way, such as television and radio.

For the rest of us, the voices of our deceased are recorded only in memories, and we don’t expect to discover one of them on a disc a quarter century after their death.

Several years ago, my father told me that Uncle Clarence, his former brother-in-law, mentioned me in their last phone conversation.

“Take good care of Cary,” he told my father. “Take especially good care of Cary.”

I don’t know what he meant, and I don’t know if it’s something he felt needed to be said because he sensed death was near. He had no children of his own but was a wonderfully doting uncle to his ten nephews and nieces.

I wasn’t singled out in his generosity, but I was the oldest, was around him the most, and inherited his love of books and politics.

He’d take me to Inman’s Barber Shop, an iconic gathering place for black San Antonians where politics were debated, civil rights actions planned, and preachers’ sermons rehearsed.

In college, when I applied to be a scholar-intern at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, I procrastinated and didn’t get all three of letters of recommendation I needed. But the one I did get, from Uncle Clarence, was so strong that it won me acceptance into the program that became one of the most important experiences in my life.

In the family eulogy at his funeral, I said that he’d lived a graceful and completed life with nothing left undone.

I wouldn’t say that now. A life is completed when it’s over, but who can speak for the dead and say they left nothing undone?

There must have been things Uncle Clarence still wanted to do, places he longed to go, experiences he wished to enjoy.

I am now 56, Uncle Clarence’s age when he died: an age I don’t know I’d have reached had he not pulled me back on the sidewalk curb decades ago. An age, I now know, where all thirsts aren’t quenched and new possibilities can still be imagined. I know that whenever I leave this world, it will be with much left undone.

I know of dreams beyond one’s reach.

Until listening to his recording, I didn’t know Uncle Clarence wanted to attend Yale and Harvard Law School. I don’t know why his plans changed, what circumstances superseded his ambition, what — if any — regret he carried into his later years.

As I write these last lines, it’s been six months since my father died, bringing the regrets of things said and not said, of visits not made or made too brief by my impatience. Before his death, I’d been lacerating myself for my poor decisions and bad choices.

But too much time lost in regrets is self-indulgent, self-pitying, and self-defeating. It averts your gaze, draws your attention away, makes you step off curbs into danger.

The discovery of Uncle Clarence’s recording reminds me that there are always voices to which we return — or that return to us — when we’re lost and seeking direction.

Voices with the strength to hold and pull us back into focus.

Voices which, from the first time they’ve awakened us, always possess the power to rouse us out of inattention and slumber. •

Feature image created by Shannon Sands. Image of Sam Cooke record courtesy of Richard Harris via Flickr (Creative Commons). Image of C. Thompson record provided by the author. Other images created by Shannon Sands.