Arriving from the North, the airplane reached Valle de la Ermita, the vast valley that nestles Guatemala City. Looking out the window, I marveled at four volcanoes that guarded the valley’s southwest. The conical colossi stood calm, mythical. Furthest west stood Acatenango, whose peak, though it belonged to la tierra, cohabited with el cielo as it surpassed an elevation of 13,000 feet. Next to Acatenango was Fuego, an active volcano whose typical eruptions only decorate the sky with a small ash plume, but whose eruption in June 2018 reminds us of the mysterious power of volcanoes. Then came Agua, earning this name after its 1541 eruption caused a great flood, though its older name Hunapú, “place of flowers,” continues to be used by the local Kaqchikel Mayans. Closest to the valley was Pacaya, the shortest and most active of the four volcanoes. After a century-long sleep, Pacaya erupted in 1965, during the early years of Guatemala’s armed conflict, as if to protest the war’s course. Although the war is now over, Pacaya has yet to return to dormancy.

The pilot flew around and around, descending in a spiral before landing on the runway of La Aurora International Airport. I stepped out of the airplane unfamiliar with Guatemala’s people, smells, and sounds. I knew only historical facts about the war. I knew that the internal armed conflict began as a consequence of the first CIA covert operation to overthrow a democratically-elected president in Latin America, that war violence lasted four decades, leaving about 200,000 people dead, mostly innocent Mayans killed by the military, and that more people had disappeared than in Argentina, Chile, and El Salvador combined. With that history in mind, Guatemala was not a comfortable place to travel to, but it was that very history that propelled me there. I arrived ten years after the signing of the peace accords with a simple question: What happens with guns after war? I expected to answer this question only as a researcher. Instead, my primary experience of postwar Guatemala was as a traveler.

The customs officer at the airport stamped my passport and told me where I could find a taxi. I towed my luggage toward the exit. Standing by the automatic glass door was a pair of armed men facing my direction, wearing different earth-tone uniforms, and each holding a rifle. I slowed down my pace while my eyes searched left and right for an explanation of their posts. I hesitated to walk past them, thinking, but the war is over. I saw travelers in front of me exiting casually, so I followed along. As I walked out, I wondered what it would have been like at this exit door during the war.

From the taxi’s backseat, I spotted more armed guards throughout Guatemala City. They were always men, wearing navy, khaki, olive, or black uniforms, sometimes accentuated with combat boots. And they carried long guns for unmistakable deterrence. The driver told me those armed men were policía privada, private police. The story goes that once the state armed forces lost control of the streets after the peace accords, robberies increased, and so did the number of private security businesses, many owned or managed by former military leaders. Apparently to keep robbers at bay, policía privada stood in front of stores, banks, restaurants, condominiums, hotels, and office buildings. Even riding on the back of trucks transporting Coca Cola. The latter appeared a harsh irony, given how workers at Coca Cola bottling plants in Guatemala suffered repression and assassination during the war for their involvement with trade unions. Bottles of Coca Cola are being protected to this day.

The taxi zigzagged through the city bustle, then stopped at a red traffic light in Zona 4. I contorted my neck trying to look at the national theater whose architecture captivated my eyes. Steep slopes and curved corners alluded to Guatemala’s prehistoric giants: pyramids and volcanoes. The theater holds the name of Nobel laureate, Miguel Ángel Asturias, who gained international prominence after he was expelled from Guatemala, a consequence of the 1954 coup. His novels were torched by the new, US-selected leaders. In some of those novels, Asturias condemned the United Fruit Company’s exploitative practices against banana farmworkers. While Asturias died in exile, United Fruit prevailed, evolving into today’s Chiquita, which continues to produce bananas and to exploit farmworkers in Guatemala.

The taxi moved again. I turned my head to see, passing between me and another car, a young man on a sports motorcycle wearing jeans, without a helmet, and with an unconcealed handgun tucked halfway into his pants — a sight many Guatemalans later assured me was unseen during the war, but becoming normal in postwar.

I settled in for my eight months in Zona 3 of the capital city against the advice of a US scholar who had done research for years in Guatemala. She said, “As soon as you get to the airport, leave the capital city; go to the highlands.” While Guatemala City lacked the opulence of the mountains and the tranquility of Mayan culture, its congested character was the perfect place for my research pursuits. I rented a nine-by-ten-foot bedroom in a cement house that had a dramatic mural in the living room drawn with green-brown mold. In the backyard, resided a seven-foot tall banana plant that didn’t bear fruit. And beyond the backyard was a ravine. My housemates believed the ravine served as a shooting range for the mara or youth gang members. Pow . . . Pow . . . Pow pow pow, I’d hear occasionally. I lived in the same city zone where notorious Mara Salvatrucha had a strong enclave. After the war, maras grew rapidly and strengthened throughout the city. Guns are their weapons of choice. A lot of the crime covered in local newspapers I read was attributed to maras. It still is. On February of 2016, Prensa Libre reported that the police found a clandestine arsenal of military weapons and ammunition, including Claymore anti-personal mines. Because the arsenal was found in Zona 3, police deduced that it belonged to Mara Salvatrucha. Despite having lived in that zone, I can’t say I witnessed the gang’s presence beyond the suspicious gunshots coming from the ravine. My neighborhood was cut off from the rest of Zona 3 by the city’s highway ring. I never ventured across the ring precisely to avoid tumbling upon gang activity, to stay safe.

Nevertheless, I often walked in the city. I walked to interviews, the supermarket, bookstores. My needs frequently led me to Zona 1, the historic center. In Secret Graves, a forensic mystery novel that takes place in Guatemala, Kathy Reichs describes Zona 1 as

the oldest part in Guatemala City, a claustrophobic hive of rundown shops, cheap hotels, bus terminals, and car parks, with a sprinkling of modern chain outlets. Wimpy’s and McDonald’s share the narrow streets with German delis, sports bars, Chinese restaurants, shoe stores, cinemas, electrical shops, strip joints, and taverns.

Reichs’s description seemed right to me, missing only the many men with guns. When walking both in affluent or in poorer commercial blocks, I’d see policía privada and, deterred, cross the street. The sidewalks were too narrow to share with a protruding gun. Soon I’d see another guard and cross the street again, amazed at the ease with which others passed by them. When I had no choice but to walk by them, some guards would whisper sexualizing remarks, revealing my failure at being as nondescript as possible, wearing straight-leg pants, loose shirt, flat boots, hair in ponytail, and no makeup. Later, I would reflect on their remarks as desperate acts given the guards’ restrictive and under-stimulating posts. Policía privada stood holding their guns for hours and hours, every day, like statues commemorating a militarized cityscape.

Not all armed guards held such restrictive jobs. Some enjoyed mobility when chauffeuring their employers to work or the children of wealthy families to school. One such guard came for me once, although I wasn’t expecting him. When the president of Guatemala’s gun rights association told me he would send his driver to pick me up for an interview, I expected a man like the taxi drivers I was used to, an average civilian wearing slacks and a button-up shirt or sweater. While awaiting the unknown driver, I felt nervous because I was going to be riding with him alone for three hours, leaving the city for a region I hadn’t been to before. From my bedroom window, I saw a black pick-up truck arrive. A fit man stepped out of the truck wearing black combat boots, black commando pants, black shirt, black safari vest, and black hair. I had already learned that men who wore vests were typically concealing guns. And so I imagined two black pistols under his vest. “Mierda,” I muttered. My housemate, who had experienced the dangers of criminal networks while driving on the highway, advised, “Don’t go.”

The time it took me to walk outside was very short, but it felt eternal as doubts and fears flooded my mind: Why did he send an armed guard? Could I be caught in crossfire? Might I be molested? Once outside, I gathered some courage extending my arm to greet the commando driver with a handshake. He didn’t expect the gesture; he shook my hand swiftly then offered me to sit in the passenger seat. The trip turned out to be uneventful. We talked about Spanish and our differing Puerto Rican and Guatemalan dialects. After establishing some rapport, the driver told me that he used to be an army soldier and that he became a private guard after the war. He preferred being policía privada because the job was flexible, safer, and better paid. He benefited from the peace accords’ demand to reduce the number of armed forces. This benefit also extended to former special-forces officers, many of whom received exorbitant salaries, I was told by someone with a “direct source,” working as bodyguards and assassins for drug cartels.

As I became better acquainted with city zones one to four, I chose, whenever possible, to walk through the quieter blocks. These blocks were mainly residential with the occasional old-school pharmacy where even ibuprofen was kept behind a glass counter. I’d also see bodegas, laundromats, and small garages turned into corn tortilla stalls, all behind locked gates. When I bought tortillas, I made contact with the seller through the space between metal bars. I’d come to the gate to see her shaping and pressing corn masa dough with her small, thick, worn hands — clap, clap, clap — while surrounded by half a dozen little children. The kids would sometimes take a bite then put back the tortilla in the stack for sale. Buyers would encounter the evidence when sitting down to lunch, a missing bite, crescent-shaped with tiny teeth marks. At the gate, I’d tell the tortilla-maker, “Una dozena, por favor,” and she’d pack, in a small, white, plastic bag, twelve warm tortillas collected either from the large, circular griddle that is typical of Guatemalan tortilla-making or from a stack next to it. Guatemalan tortillas are thicker and fluffier than Mexican ones. Following local tradition, I would roll the doughy disk then dip it in refried black beans.

Walking in the city also brought me close to images of postwar, like the one I stumbled upon when seeing a file of about 15 men on the sidewalk in Zona 1. The men were waiting to enter the Department of Arms and Ammunitions Control. During the war, only those few civilians with ties to the military would be given a gun license, and without having to wait in line. After the war, so many men wanted a permit to carry their pistols that the waiting line snaked out the building.

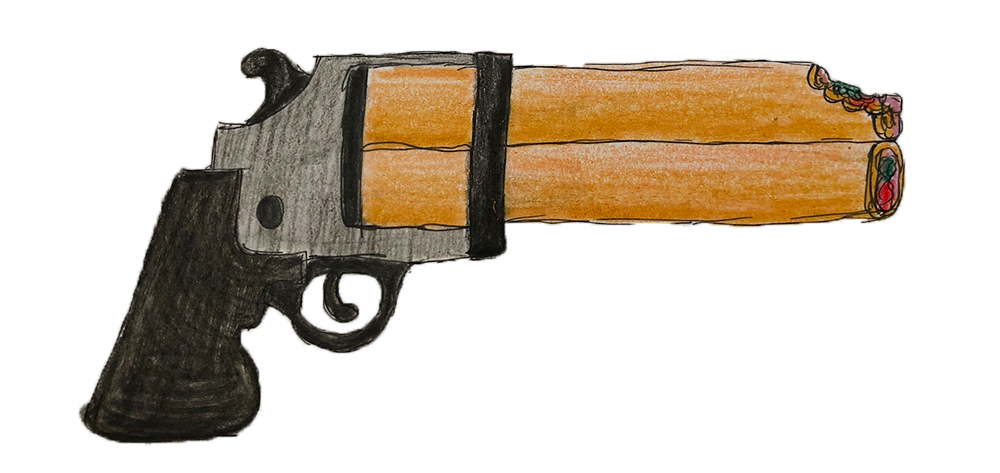

While the number of legally registered guns increased after the war, so did the quantity of illegal guns. “And the number of armas hechizas have also increased,” told me a colonel at the Ministry of Defense — the very ministry that manages the department of arms control. Armas hechizas or enchanted guns are homemade guns that use regular ammunition. Today, armas hechizas are used by mara members who can’t afford to have a regular arsenal. But the history of homemade guns began during the war when the guerrillas crafted many of their own firearms. The colonel showed me some. He guided me down broad outdoor stairs at an old fort. The last set of steps was encased by walls. As I stepped down next to the colonel, a memory that wasn’t mine flashed past me like a quick shiver. I thought of the many Guatemalans who walked down similar stairs, or were dragged down, because they dared fight for a dignified life during the war, as did Hector Gamez, a man who had demanded from the army information about disappeared friends and family. In Searching for Everardo, Jennifer Harbury tells of the death of Gamez:

He was forced into a car by armed men in broad daylight, in front of terrified witnesses. The next day his body was found dumped into the dusty streets not far from his home. He had been savagely beaten, his skull crushed, his liver ruptured, his tongue slashed out of his head. Death had come slowly, not from the beatings, but from the wounds dealt by a blowtorch.

At the bottom of the stairs, the colonel and I passed an open gate, then turned right to find several men in uniform standing around two long tables covered with firearms. Some were as old as a Reising submachine gun and others were hechizas. A few had an attachment, a letter-size paper turned yellow and spotted with rust stains. One read, in translation from its original in Spanish:

Enchanted Shotgun, F-P

Seized in armed confrontation against terrorist delinquents,

the day of 02FEB84 in the municipality of Nebaj, Coordinates (9505)

With the soldiers around me, I took a close look at the gun, then a snapshot. The enchanted shotgun was crafted using wood, plumbing pipes, and reusable parts from a manufactured rifle. It resembled a military weapon, unlike the minimalist look of maras’ hechiza guns that I had seen in local newspapers.

•

One late-morning, walking back from the gym in Zona 1, I heard a gunshot. I stopped, then saw that two young women in the intersection ahead also stopped. With arms around each other, they stared with caution into the block before them, where the noise had come from. They weren’t scared enough to reverse their course. After a short pause, they crossed the street and continued onto the suspect block. I walked to the corner and peeked around. Outside a house’s open door, an old man wearing a ranchero hat was jumping on his left foot. His face expressed pain. Either he shot himself in his right foot or someone else did. I couldn’t see a gun. Across the street from the wounded man, a curious woman peeked from her door keeping all but her head inside. A little boy squeezed by her side, extremely curious himself, but before he could step out the door, the woman hushed him back in. A man on the street went to help the victim and yelled, “¡Llamen a los bomberos!” / “Call the firefighters!” The bomberos tended to all types of emergency calls, many in response to gun violence. I watched for another minute. On the next block over was the street market where I would buy bananas, pineapples, papayas, and other enticing fruit. Some folks were still looking toward the wounded man’s house, but most went on with their business as if the incident had never happened. If someone else shot the man, they must have ran in the direction of the market. I decided to skip my shopping that day. As I walked back home via an unplanned path, I reflected on what the director of the think-tank Security in Democracy once told me during a conversation about postwar violence. In a downbeat tone, she said, “If we’re going to talk about the results of the war, I would consider the psychological part. This is a society that got used to living in war, that learned la violencia.”

La violencia is a term used by many Guatemalans to refer to armed violence. Most victims of la violencia were linked to narcotrafficking and youth gang activity. Most, but not all. I bought the five major newspapers on a daily basis and was continually troubled by what I read. A teacher is shot. A girl dies during armed attack, two more are wounded. Lost bullets, tragedy in Xela. Bus passengers are attacked from a car. A grandmother, daughter, and son are massacred with gunshots.

In the papers, I read about armed bus passengers (civilian men presumably bearing a gun license) who attempted to shoot robbers seeking petty cash. The random shooters often missed their target and hit instead the driver or fellow passengers, including children. In reading these stories, I learned to avoid public transportation within the city. But chaotic shootings were not exclusive to buses or to men taking justice into their own hands. The director of Security in Democracy shared, “A friend of mine was shot four months ago, here on this avenue,” she said pointing at the window. “He was driving out of work on a Friday afternoon when a car overtook him, so he honked. The man in the other vehicle got out and shot him. The car had seven bullet impacts; one hit my friend in the arm.” More people told me about armed drivers who intimidated others by showing their guns and who often fired at drivers whose horns pestered them. I couldn’t avoid riding in taxis, but when I traveled, I was alert to every honk.

“What about the police?” I would ask during conversations about crime. One urban resident responded plainly, “Police officers are agents of insecurity.” A human rights advocate shared some background: “We have ex-military officials leading the police. The peace accords ordered dissolving the wartime National Police using El Salvador as a reference, where they fired all the officers and recruited new ones. Here the police were recycled. A small group was fired and the others were given three months of training.” Showing me three fingers, she added sarcastically, “And three months of training was enough for them to stop being the corrupt and militarized National Police to become the new National Civil Police.” Three months compared to 36 years of counterinsurgency operations. She leaned back in her chair and crossed her arms as if to resist what she was about to say, resist accepting it as part of Guatemala’s recent history, and concluded, “Later, the government of President Alfonso Portillo removed those who were more or less new and reinstated the corrupt ones.”

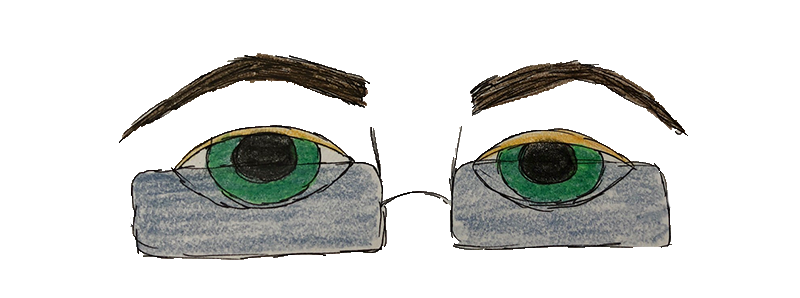

I rarely saw police officers. Their visual scarcity was compensated by the widespread presence of policía privada. And also by the less conspicuous yet just as prolific presence of armed civilians. During an interview with a physician, I confessed to him my surprise at seeing so many armed people. He let out a short, dry laugh. At first I thought my ignorance alarmed him, but soon I learned that my disclosure had only amused him. He said, “This is an armed country, and armed to the teeth.” Seeing that he didn’t carry a gun, I pried on the matter the second time we met, “Do you have a gun?” He shrugged and said, “I have a gun,” then paused briefly. “Not one. At home I have a 12-calibre shotgun, and in each on my daughters’ bedrooms is a 45 pistol. My wife is best at shooting a hunting rifle I keep under the bed. We have them for defense.” Unlike most armed civilians today, he had had guns since the war. Then the doctor told me more about what wasn’t in public sight. “I assure you, I’m a witness,” he said widening his eyes enough that I could see they were green through his frameless glasses, “that many army officials, who were or still are in the army, are storing armament including explosives because they’re convinced that there is going to be a new war in Guatemala.” He concluded in a calm yet declarative tone, “Porque acá no hay paz.”

Paz was once a hope, an expectation after war. By the time I went to Guatemala, any expectation of peace had vanished. The doctor’s words, “there is no peace here,” gave title to my labyrinthine exposure to postwar Guatemala.

One afternoon I visited a Guatemala City gem, the Mercado Central. Located behind the Metropolitan Cathedral, at the heart of Zona 1, the big market is a stimulating maze of local colors, scents, and noises. Fuchsias, reds, greens, blacks; raw meats, ripe fruits, and leather; chatter and whispers in Spanish and in any of the other 20-some languages of Guatemala that I could only identify as Mayan. As I left the market, I saw an elderly Mayan woman on the sidewalk. She sat on what I pictured was a very short stool concealed by her intricately woven skirt. She was selling tamales de elote. These tamales are a treat, fresher and sweeter than the ones made with corn masa. The tamale-maker kept her stock wrapped in corn husks and warm over a small metal grate that let out wood-scented smoke. Her graying hair and wrinkled copper skin told me she had survived and witnessed more than I could ever withstand knowing. So many Mayan villages were burned down as part of the counterinsurgency operations, so many inhabitants were displaced if not killed. She handed me a tamale and I gave her two quetzales, the equivalent of a quarter. Then I crossed the street to Plaza Mayor.

The plaza covered half a square kilometer with a large fountain at its center. To the north spread the long, green stone National Palace where the Peace Accords were signed, and where President Bill Clinton publicly regretted the US “support for military forces and intelligence units which engaged in violence and widespread repression.” I strolled to the fountain, then sat at its edge to eat my snack. Behind me, water dripped down one, two, three gradually larger bowls and then into the ground pool. Before me, I contemplated the Metropolitan Cathedral with two bell towers in sand color, tall wooden doors, and an exhibit of wartime terror: 12 pillars carved with names of the disappeared, a euphemism for civilians considered subversives who were abducted, tortured, and executed, and then whose bodies were hidden during the war — a continued torture to their families. The memories of war dwelled in many city places and spaces. I wondered if and how Guatemalans ignored those memories.

After eating my snack, I walked north toward the National Palace to attend the public presentation of Guatemala’s first Policy of Human Rights. Standing at the podium, a Mayan woman wore a traditional, colorful headband that clashed with her somber expression. She represented the Mayan Guatemalans who had suffered and continued to suffer most from human rights violations. After her, spoke the human rights ombudsman, a Guatemalan of European descent, who was giddy before the couple-hundred-person audience. He praised the policy as a symbol of democracy. He shared how long he had worked on and waited for this policy, finally recognized by the government two decades after the transition from authoritarian rule to democracy. Two decades. I wondered how long would it take for postwar peace and security to transpire. I felt pessimistic. When I arrived in Guatemala, I had expected to witness the sprouts of peace building, perhaps even some disarmament initiatives. Quite the opposite. I witnessed the increase of firearms, particularly among the civilian population, as well as the spread of armed violence beyond two warring parties. My experience of postwar Guatemala included neither paz nor its promise. Perhaps it will come only after the Pacaya volcano returns to dormancy once again.

After the policy presentation, I stepped out of the National Palace to see the sun was setting. Curfew was about to begin. During the war, state armed forces managed curfews. Afterwards, the fear of becoming a crime victim enforced curfew with similar effectiveness. Come dusk, most people on the streets headed home, including myself. I decided to use the twilight time to make the 25-minute walk home. I knew exactly which path to take so as to feel the safest. By the time I entered the last block on Zona 1, before crossing to Zona 3, it was night. The post light gave the street an amber tint. A few steps into the block, I saw a boy, about ten years old, holding a black pistol. For a moment I thought he held a toy; my mind could only associate the child with a toy, not a real gun. Walking fast in the middle of the street, he tucked the pistol in the front part of his pants. The gun was real, the way it weighed down his hands and pants. By then I knew the weight of a pistol. A younger boy, about seven, wanted to see, touch, grab the gun. Annoyed at the childish excitement, the older boy secured the pistol with one hand and with the other briskly covered it with his shirt then jacket. He walked on with a most serious expression. Aside from the three of us, the block was deserted. An unusual experience in the neighborhood where I bought tortillas and fruit. I continued at my regular pace on the sidewalk as we passed one another, wishing they would ignore me. They did. When I reached the end of the block, I turned just my head to look back and lock-in that memory of postwar Guatemala. The boys stepped out of the light into the darker side of the street. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.