The science of eggs is called “oology” (from the Greek “oion”) and not, as one might have guessed, “ovology.” Is interest in the outer covering of an egg an expression of the joy the observer feels as they anticipate the new life forming, unseen, inside? That is doubtful, because the act of collecting blown eggshells and storing them in boxes, drawers, and cupboards — taking them out from time to time to dust them off — pretty much shoots that theory down. Is there any connection at all between marveling at the object and appreciating the bird? It hardly seems possible that the urges to collect eggs and to delight in birdwatching could coexist in the mind of one person. Perhaps it is only the egg in all its flawless perfection that fascinates, and what the observer experiences is an appreciation for the object in and of itself?

Until the latter half of the 19th century, egg collecting was a particularly popular pastime among bird lovers. Even though collecting eggs came with its own set of challenges, the eggs, unlike bird skins, did not need any special treatment to make them last so they could be stored and displayed. All collectors needed to do was blow them out. However, it has to be said that it is often difficult to identify individual eggs in a collection, because although all kinds of claims can be made about an egg, it is impossible to prove the exact species an individual egg belongs to or exactly where it was collected. You have no choice but to rely on information provided by the collector. To complicate matters, disreputable collectors sometimes painted their eggs to match those of rarer species so they could charge unsuspecting buyers a higher price.

Oology was often connected to far-fetched theories that make no sense to us today. For example, Jean Guillaume Rey (1838–1909), an introverted individual who was born into a French emigrant family in Berlin and who practiced chemistry at home, owned a large collection of birds’ eggs and was particularly interested in the brood parasitism of cuckoos. He tried to draw connections between the patterns on birds’ eggs and how birds were classified.

Ornithological journals were first published in Europe the 19th century, and eggs were always a hot topic in them. There were reports of misshapen eggs — eggs with flat sides or sharply pointed ends, or long, thin eggs with grooves along their sides. There were also “eggs within eggs,” which came in different shapes — usually, an egg the size of a walnut and without a yolk was found within a larger egg. From the way they wrote about them, you would be forgiven for thinking that collectors believed in the magical powers of eggs, although they stopped short of crediting them with the supernatural properties sometimes conferred upon them by non-Western cultures.

There were some outstanding collectors. As co-owner of a business trading in natural history specimens, Franz Kricheldorff (1853–1924) traveled to China and Tibet on collecting expeditions on behalf of such patrons as Lord Walter Rothschild. Apart from his commercial activities, he also maintained a comprehensive and important egg collection, which he had built up over decades. One connoisseur once called it “a testament to German industry and aptitude.” The collection included 310 cuckoo eggs, most of which were collected from warbler nests.

Some egg collectors were so obsessive that not just any egg would do. In his book The Most Perfect Thing, biologist Tim Birkhead tells the tale of George Lupton, a wealthy lawyer from Yorkshire, England, in the 1930s, who commissioned those who plundered nests on the limestone cliffs of Bempton to procure for him the same beautiful brown eggs with unique markings from the same female guillemot (murre) every year — for two decades. His focus on this unfortunate bird meant that for all of her breeding life she “never once succeeded in hatching an egg or rearing a chick.”

When he was six, Max Schönwetter (1874–1961), who later became a surveyor, found the remains of a partridge egg with blood vessels still sticking to it, which is said to have provoked in him an unquenchable desire to study birds’ eggs. Over the course of 60 years, and with the help of people who traveled, he amassed a private collection that included the eggs of almost four thousand species of birds. The smallest egg — from a bee hummingbird — was the size of a pea. It was one-fifth of an inch (five millimeters) long and weighed in at an infinitesimal fraction of an ounce (one quarter of a gram). Schönwetter brought that delicate object, as well as a three-and-a-half pound ostrich egg and all the other eggs in his collection, unscathed through two world wars. According to ornithological historian Ludwig Gebhardt:

In his old age the confirmed bachelor could claim to have examined more eggs than any other person alive or dead, and no other method of comparing eggs was more thoroughly thought through or more detailed in its methods than the one he had devised.

His lifelong study of the morphology of eggshells, which he pursued with dogged determination while surmounting repeated troubles, disappointments, and difficulties, culminated in 1952 with the publication of his life’s work, Handbuch der Oologie (Handbook of Oology).

Another particularly noteworthy collector was Alexis Romanoff (1892–1980), a Russian who immigrated to the United States in 1921. Shortly after he arrived, he began to devote his life to eggs. While he was studying for his doctorate at Cornell University, he decided to publish the world’s most authoritative book on the biology of the egg. He worked on it for 20 long years along with his wife, Anastasia — day in, day out, including evenings and weekends, distracted by neither children nor travel. The Avian Egg, almost one thousand pages long with 435 illustrations, appeared in 1949 and was a huge success with experts in the field.

The first bird lovers to express concern about and argue against the damaging and unnecessary practice of egg collecting began clamoring to be heard in the middle of the 19th century. Toward the end of the century, they were increasingly attracting the attention of bird conservationists and soon after that, law makers. For the American nature writer John Burroughs (1837–1921), egg and skin collectors are “men who plunder nests and murder their owners.” At the annual meeting of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in 1922, a warning was finally given about the “distinct menace” posed by the egg collectors, whereupon Lord Walter Rothschild, who felt he had been slighted, split off from the Royal Society and helped found the British Oological Association.

Dedicated to egg collecting, it was later renamed the Jourdain Society after one of its founding partners. Meetings of the association were targeted by police in the 1990s — it is a mystery how they managed to meet for so long — and more than half the members were fined for illegal possession of eggs. Like members of a terrorist organization, members hid their identities when they were interviewed. The ban on collecting eggs of protected species of birds seems to have merely increased the appeal of doing exactly that.

The most comprehensive collection of birds’ eggs in the world can be found at the Natural History Museum at Tring in England (which came under the direction of the Natural History Museum in London in the late 1930s). It comprises approximately two million specimens. The eggs are stored in the basement in locked cabinets. The collection achieved a certain notoriety in the 1960s when Derek Ratcliffe (1929–2005) was researching why peregrine falcons were not breeding successfully. When he compared their eggshells with older ones from the museum, he noticed how thin they had become, a defect that was linked to pesticide use. Later, DDT was banned throughout Europe.

The names of some egg collectors are inextricably linked with criminal activity. Take, for example, Londoner Matthew Gonshaw, who had already served three prison sentences when he was convicted in 2004 for having collected 600 eggs, 104 of which he had hidden in a secret compartment in his bed frame. Typically, he wore camouflage when he went egg hunting and carried not only topographical maps, a climbing rope, and a survival manual like those used by the military, but also a whole battery of syringes he used to remove the contents of the eggs on the spot.

Then there is the remarkable case of Mervyn Shorthouse, who was convicted in 1979 of having, over the course of three years — during which he visited the Tring museum at least once a week — made away with an estimated ten thousand eggs. As a regular visitor, he had gained the trust of the staff and aroused no suspicion, because he posed as a wheelchair-bound invalid. The museum could perhaps have recovered from the loss of the eggs; however, because Shorthouse wanted to cover up the theft, he mixed up all the labels, thus considerably reducing the value of the most comprehensive historical collection in the world. Shorthouse is the reason the collection is carefully locked away today.

Compulsive egg collecting is not confined to Great Britain. For example, in the recent past, police in Finland confiscated ten thousand eggs from the house of a man who was suspected of being a member of a network of Scandinavian egg collectors, some of whom were trading in the eggs of protected species.

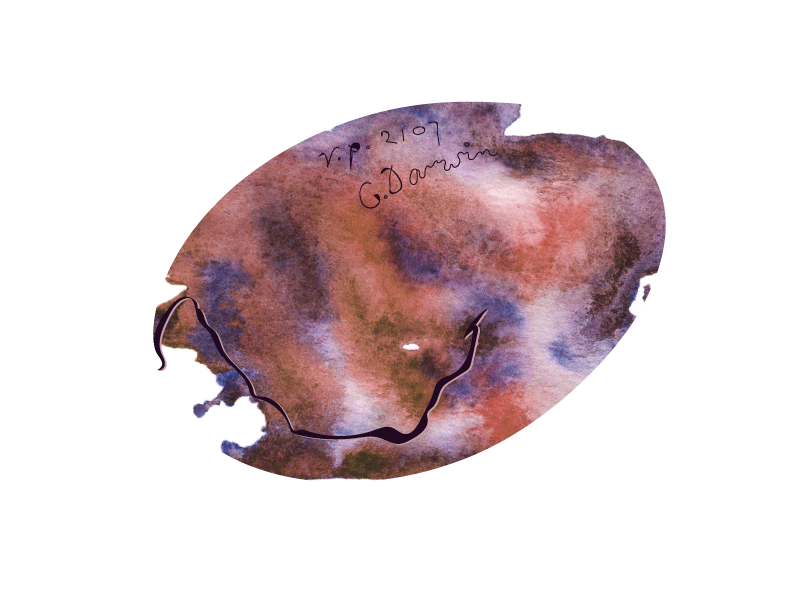

One particularly special egg that has not yet fallen into the clutches of the egg mafia is the only one that remains from Charles Darwin’s legendary journey on HMS Beagle. It was discovered by chance in 2009 in the zoological museum at Cambridge University in England, when a volunteer was cataloging the collection — at the time she found the egg she was ten years into her task. The egg is probably from a spotted nothura from Uruguay. The dark-colored specimen is cracked and bears the name C. Darwin. The shell cracked when Darwin tried to put the egg into a box that was just a little too small for it. “To have discovered a Beagle specimen in the 200th year of Darwin’s birth is special enough, but to have evidence that Darwin himself broke it is a wonderful twist,” collections manager Mathew Lowe reported.

Modern oologists go beyond eggs as objects and research them to discover what they might tell us about the birds themselves and their behavior. Birkhead reports in his book on the ways that guillemot eggs are designed to resist contamination by guano in the messy environs of their colonies: their surfaces are covered with “a mass of pointy peaks” to keep the guano off, and they are laid narrow end first — which is unusual, but ensures that the wider end that encloses the chick’s head and air cell remains relatively feces-free. Guillemot eggs are also longer than most birds’ eggs, helping to keep them grounded on the rocky ledges where guillemots make their nests. British researchers Emma J.A. Cunningham and Andrew F. Russell have found that female mallards invest in larger eggs when they mate with more attractive males. Beautiful as they are, there really is more to eggs than meets the eye. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.