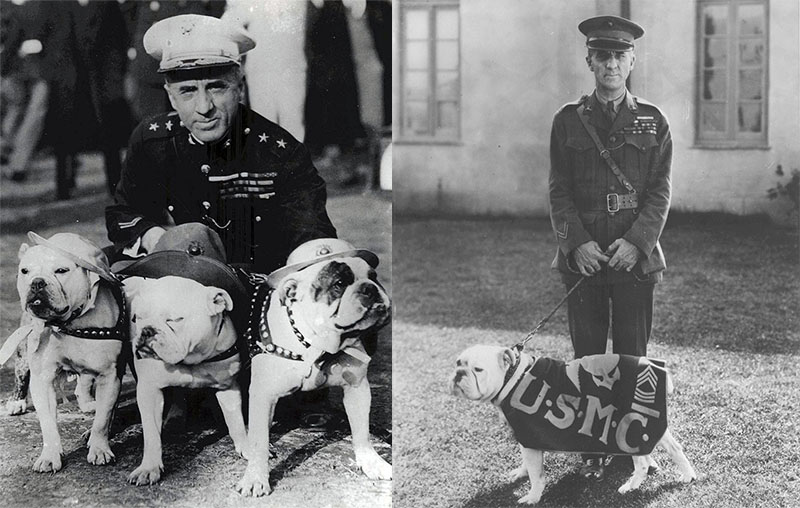

Smedley Darlington Butler was a Major General in the Marine Corps and the only “Devil Dog” to ever win two Medals of Honor and a Marine Corps Brevet Medal. For two years, Butler, known occasionally as “Old Gimlet Eye,” was the Director of Public Safety for his hometown of Philadelphia. Given the unenviable task of enforcing the Volstead Act in extra wet Philly, Butler’s first forty-eight hours in office constituted a “shock and awe” campaign against the city’s illegal speakeasies, cabarets, brothels, poolrooms, and other dens of iniquity. According to Hans Schmidt, Butler’s greatest biographer and the author of Maverick Marine: General Smedley D. Butler and the Contradictions of American Military History, in those two days Butler and his men closed down 973 of the 1,200 saloons that sold blackmarket hooch in the city, while another 80 percent of known underworld haunts were closed temporarily. Philadelphia bootleggers showed their appreciation for Butler’s tactics by firing shots at the top cop one morning in 1924.

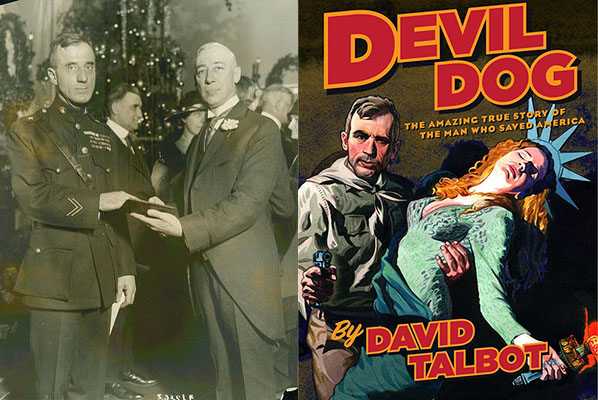

By the summer of 1933, most Americans knew Butler as a national hero, a civic reformer, and a man of action. What they didn’t know was that Butler was being groomed to be their dictator. That summer was not a good time to be an American citizen. The Great Depression, which was almost four years old, showed no signs of stopping or slowing down. Even with President Roosevelt and his much-vaunted New Deal, stomachs were still starving, men still weren’t working, and money was still scarce. As a result, many alternatives were suggested in newspapers, on street corners, and in smoke-filled boardrooms. Back then, before the great bloodletting of World War II, serious and otherwise rational people looked towards fascism, communism, and even national socialism as possible panaceas for a world gone mad. After all, democracy and capitalism were failed gods, so some kind of revolution was in order.

Unbeknownst to most, a plot to overthrow the government was already underway. According to the testimony he gave in front of the McCormack-Dickstein Committee, which was the first installment of the House Committee On Un-American Activities, Butler claimed that he was approached by two leaders of the American Legion on July 1, 1933. Specifically, these men were named Gerald C. MacGuire and William Doyle. Initially, McGuire and Doyle sought out the popular Marine officer as a candidate for the national commander of the American Legion. The convention in Chicago was only three months away, so Butler’s enthusiasm had to be gauged quickly. Unfortunately for MacGuire and Doyle, Butler was not interested.

Not satisfied, the men continued to pester Butler with offers. MacGuire and Doyle asked Butler if he’d be willing to give a speech at the American Legion’s Chicago convention in support of returning the U.S. to the gold standard (FDR had only taken the U.S. off of the gold standard a month before on June 5, 1933). Again, Butler declined. At some point, MacGuire and Doyle began hinting at darker motivations. They showed Butler a bank account worth almost $50,000, while simultaneously flashing around even more money. They began talking about guns, too — a lot of guns.

Next, Butler was introduced to Robert Sterling Clark, a former Army-officer-turned-art-collector who had served in China alongside Butler. Thanks to a recent inheritance, Clark was a millionaire. He too wanted Butler to make an appearance at the American Legion convention. For a year, Clark, MacGuire, and Doyle continued their wooing of Butler. More money was thrown at him, while MacGuire began sending Butler and the others postcards and letters from his trips to Europe. Noticeably, MacGuire’s correspondence mentioned meetings with several right-wing groups, including fascist organizations in France. At first, MacGuire claimed that he was studying “economic conditions.” Then, once it came time to be blunt, MacGuire and the others finally told Butler what their ultimate aim was nothing less than an armed coup. Headed by World War I veterans and backed by a shadowy cabal of businessmen and financiers, the plot, which would later be called the Business Plot or the Wall Street Putsch, sought to turn Butler into an American Mussolini.

The planned takeover failed largely because Butler went to the authorities. While Butler’s story was considered a fantasy at the time, later historians conceded that a plot was almost certainly being discussed. For Butler, the Business Plot and the Great Depression only pushed him further towards radical politics. Once a Republican candidate for a Senate seat in Pennsylvania, Butler became a pacifist and an anti-war socialist during the mid-1930s. Famously, Butler penned a glorified pamphlet called “War is a Racket.” In post-World War I America, especially during the Depression era, adhering to strict isolationism was not considered terribly abnormal. That said, the aggressive denunciations of war, war profiteering, and capitalism in “War is a Racket” were shocking because of their source. Despite lying about his age in order to take a commission as a second lieutenant during the Spanish-American War, and despite a thirty-year career spent fighting wars in China, Nicaragua, the Philippines, Haiti, and elsewhere, Butler bleakly summed up his legacy in “War is a Racket” by claiming that he had been nothing but a hired gun for Wall Street.

I served in all commissioned ranks from second lieutenant to Major General. And during that period I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism. I suspected I was just part of the racket all the time. Now I am sure of it.

Alongside such bleak summations, Butler’s well-received text also stumped for typically left-wing causes such as increased wages for workers, while at the same time arguing for the conscription of “capital and industry and labor before the nation’s manhood.” Let the bigwigs fight, Butler argued, especially since they’re the ones that start wars in the first place. Better yet,“War is a Racket” also proposed that the American armed forces be reduced in number so that they could only perform defensive operations instead of aggressive campaigns.

While “War is a Racket” caused quite a stir when it was released (and remains a cornerstone work read by anti-war libertarians and socialists alike), in some ways its vitriol was in keeping with Butler’s history. In or out of uniform, Butler was an iconoclast who frequently butted heads with his superiors. In January 1931, while delivering the speech “How to Prevent War” in front of the Philadelphia Contemporary Club, Butler recounted a story that had been told to him by an acquaintance. Apparently, while traveling through Italy with Benito Mussolini, Butler’s friend had watched in horror as the fascist dictator ran over a small child with his top-of-the-line automobile. Worse, even though both men could hear the crunch of the boy’s bones underneath the wheels, Mussolini refused to stop and had the audacity to claim that one life was insignificant. For such an inflammatory story, the Italian government demanded an apology. The United States not only issued one, but took things a step further when President Herbert Hoover ordered the beginning of court martial procedures against Butler. Ultimately, Butler requested an early retirement and left active duty in October of that year.

Years before, despite being the scourge of the Philadelphia underworld, Butler was drummed out of the city for being too heavy-handed. Butler was the type of police chief who kept career politicians up at night with nightmares about his big mouth. You see, Butler was loved by the citizens of Philadelphia, most of whom appreciated the Marine’s candor. In the press and on the radio, Butler had no problem airing his grievances about the lack of support he received from the mayor’s office. Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick, who had brought Butler to Philadelphia after receiving a glowing recommendation from none other than President Calvin Coolidge, was obviously not a fan of Butler’s frankness.

Still, even though Butler failed to eradicate bootlegging and police corruption during his tenure as the Director of Public Safety, he did manage to accomplish some long-lasting reforms. He centralized his authority over the entire department while reducing the number of police districts in the city. Butler also oversaw an increase in manpower, which, coupled with his numerous raids on predominately working class drinking establishments, drew the ire of Philadelphia Democrats, many of whom complained that Butler’s definition of anti-liquor enforcement was a type of class warfare. In response, Butler’s department began targeting hoity-toity watering holes like The Ritz-Carlton, the Beaux Arts, and the Bellevue-Stratford Hotels. When these raids drew even more criticism, Butler threw up his hands, called the whole system “crooked,” and began publicly accusing Mayor Kendrick of being “disloyal” to the cause of law enforcement.

Butler may have also created the first “militarized” police department in the U.S. Today, because of Ferguson, Chicago, and the Black Lives Matter movement, the issue of police militarization is contentious. Many, like author Radley Balko, worry that our law enforcement officials are now taught to think and act like “warrior cops.” In Butler’s time; however, the military provided the perfect model for modernizing police departments to emulate. From the birth of professional police academies to the creation of specialized units with military-style ranks, police departments in the 1920s were beginning to look and act more and more like paramilitary organizations. The Philadelphia Police Department under Butler did not only adhere to this trend, but according to Dr. Ellen Leichtman’s “Smedley Butler and the Militarisation [sic] of the Philadelphia Police, 1924-1925,” it may have been an “extreme” example of police militarization.

As it turns out, Butler’s military career is similarly intriguing for students of current events. Unlike the much more celebrated military careers of men like Dwight D. Eisenhower and even the cantankerous George S. Patton, Butler’s time in the sun occurred during a highly controversial period of American military interventions abroad. Like the present U.S. conflict in Afghanistan, Butler’s Marines were tasked with pacifying the turbulent nations of Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Haiti for decades. In each of these conflicts, U.S. Marines backed by U.S. Navy warships undertook nation-building programs that were designed to implement and support pro-American governments throughout the Western Hemisphere. When not fighting local insurgents, who mostly used guerrilla tactics that emphasized hit-and-run ambushes accompanied by well-placed dynamite, Butler’s Marines were busy training local police and army recruits. As was his fashion, Butler rarely made friends along the way, and he famously angered Haiti’s privileged creole class by officially saying that: “no preference [will be] shown any negro owing to a supposed superiority due to the infusement of white blood in his veins.”

Such statements define the contradiction that was General Smedley Butler. A Marine’s Marine and a consummate professional, Butler nevertheless was a combative, stubborn, and hot-tempered contrarian. But of all the contradictions in Butler’s life, none resonates more today than his status as America’s most decorated peacemonger. At different points in his life, Butler was a darling of the political left and right. He was, like a lot of American conservatives before World War II, an isolationist who was skeptical of nation-building and imperialism. On the other hand, Butler’s views on capitalism mark him as sympathetic to Marxism. Butler’s days as a leader of men in combat almost certainly undergirded these views, especially since Butler’s greatest achievements came during the politically muddy age of America’s first engagement with counter-insurgency warfare.

Back home and out of uniform, Butler’s experiences in Philadelphia only served to further sour him on the idea of “business as usual.” If war was a racket, then politics was an even bigger racket. Butler had been personally brought to the city in order to defeat the growing menace of lawlessness and police corruption, and yet when he did just that, his superiors told him to back off. Philadelphia, it turns out, was something of a banana republic in the 1920s. This time around, Butler did not win the war. “Old Gimlet Eye” grew jaundiced. The Great Depression and the Business Plot finally turned him gangrenous. The man known as the “Fighting Quaker” used the remaining days of his life to fight for a certain brand of conspiracy thinking. Many Americans have made the same decision since then, especially since our post-9/11 history has been filled with so much moral ambiguity. Frankly, it’s surprising that we haven’t had another Smedley Butler in the 2010s. But, if the 2016 presidential continues on as is, then maybe another populist rabble rouser will come to the fore in order to expose another racket. •

Feature image courtesy of USMC Archives via Flickr (Creative Commons)

Other images courtesy of USMC Archives and Martha Heinemann Bixby via Flickr (Creative Commons)