When revolt has no object, it turns on itself, opposing all imagined foes in wanton destruction of imagined barriers. Most apparently since the advent of Romanticism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, revolt has often been focused on an object considered in more personal terms — the introspective rebel pitched against disinterested systems and in search of a soul divested of the stain of acquisition, the taint of the tangible. Yet, sometimes, all the rebel finds is empty space where identity used to dwell. And this is where we find ourselves in the West today, with open, democratic societies in the grip of revolt against rationalism and its accompanying pluralism.

Pankaj Mishra, in Age of Anger, asserts that Rousseau, a scion of Enlightenment thinking and one of its chief antagonists, saw the danger of shunting the religious, the provincial, and the irrational to the margins and the shadows. Rousseau asserted, after all, that social injustice originates not with the individual but with the existence of institutions. Despite this warning, more repressive forms of nationalism took shape and grew ominously over the next two centuries, culminating in Nazi and Soviet forms of totalitarianism.

And the persistence of pathological nationalism is undeniable. Whether it’s the debased atavism of so many Trump supporters or the rancid parochialism of so many Brexiters, resentment and entitlement still produce superfluous-feeling individuals tilted against the rational state apparatus that denies (or at least complicates) their nationalistic or ethnic sense of identity. But that rage just might have a deeper source than mere politics. Two of the books that profoundly reveal and explore the formless rage that precedes revolt are Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl.

Mishra, again in Age of Anger, recounts how Dostoevsky visited the Crystal Palace at the International Exhibition in London in 1862. Lamenting the worship of rationalism and materialism on display, he reflected on how, “you become aware of a colossal idea; you sense that here something has been achieved, that here is victory and triumph. You even begin vaguely to fear something . . . Must you accept this as the final truth and forever hold your peace? It is all so solemn, triumphant, and proud that you gasp for breath.” This is the damned seed that blooms into the angst of the the Underground Man in Notes from Underground, which would be published two years after that fateful trip. Mishra rightly observes that the rationalist/utilitarian ethic celebrated at the London exhibition prefigures the distrust of such an ethic pervasive in Dostoevsky’s subsequent major novels.

The Underground Man may be one of 19th century literature’s most grating malcontents, but he’s also an irresistibly imploding critique of both bourgeois practicality and revolutionary ideology. As he more than hints throughout “Underground” — his meandering monologue that comprises one third of the novel — rationalism and materialism are gossamer over a nihilistic oblivion which, once glimpsed, is inescapable. Nietzsche warned of the risk of staring into the abyss because the abyss might just stare back into you, and that’s what the Underground Man is for the reader: the degrading abyss staring back into you, acidifying your psychological balms and rendering your social status void, without replacing them with any sustainable truth. The Underground Man even goes so far as to proudly denigrate himself by provoking the reader:

Not just wicked, no, I never even managed to become anything: neither wicked nor good, neither a scoundrel nor an honest man, neither a hero nor an insect. And now I am living out my life in my corner, taunting myself with the spiteful and utterly futile consolation that it is even impossible for an intelligent man seriously to become anything, and only fools become something.

Wondering whether he truly believes his diatribe misses the point. He’s beyond believing anything, and that’s what makes him so slippery and terrifying and alluring. And yet he’s not just a growling abyss. Oddly, there’s a kind of dysfunctional social insight he displays when he spends an evening with his former schoolmates and with the prostitute, Liza, the only character in the book who exhibits any real empathy for him. He seems to understand them either really well or not at all. And that mutated social insight leads him paradoxically to mire himself deeper in his own isolation, as if he realizes the futility of relationships and his own abject existence. Yet the desire, the need for affirmation from the outside world persists, at least in his own inverted kind of way.

I have, for example, a terrible amour propre. I am as insecure and touchy as a hunchback or a dwarf, yet there have indeed been moments when if I had happened to be slapped, I might even have been glad of it. I say it seriously: surely I’d have managed to discover some sort of pleasure in that as well — the pleasure of despair, of course, but it is in despair that the most burning pleasures occur, especially when one is all too highly conscious of the hopelessness of one’s position.

The Underground Man knows the problem, but that doesn’t mean he can extricate himself from it. He sees the pointlessness of rationalism, material acquisition, and status-clamoring, and so he just can’t help himself in critiquing rationalist ideologies by exclaiming

Profit! What is profit? And will you take it upon yourself to define with perfect exactitude precisely what man’s profit consists in? And what if it so happens on occasion, man’s profit not only may but precisely must consist in sometimes wishing what is bad for himself, and not what is profitable? And, if so, if there can be such a case, then the whole rule goes up in smoke.

Turns out enlightened self-interest is a quite likely a delusional contrivance. Shocking as it may be to some blinkered market worshippers, self-interest may not be in others’ interest, nor, for that matter, anybody’s interest who happens to not be living in total isolation.

Though without a political program of his own, the Underground Man’s formless rage against rationalism and ideology is echoed in a way by so many far right agitators today, except theirs isn’t so much a rebellion against rationalism per se, but against one of its chief byproducts: pluralism. Eric Kaufmann, writing in November of 2016 for the British Politics and Policy blog of the London School of Economics, argues persuasively that rational immigration policies in the US and the UK are fueling the rise of anti-rationalist xenophobia and bigotry. He notes the US was “90% white in 1960, is 63% white today and over half of American babies are from ethnic minorities.” Similarly, in the UK, the influx of Eastern European migrants influenced how Britons cast their vote for or against Brexit. “Local ethnic change,” he writes, “is linked with a much higher rate of Brexit voting. From under 40% in places with little ethnic change to over 60% voting Brexit in the fastest changing areas.” It’s clear that the pre-Trump, pre-Brexit governments in the US and the UK recognized the economic and cultural benefit of rational immigration policies. What’s less clear is how to contend with a significant segment of the population so exasperated by cultural change that they’re willing to jeopardize the fundamental economic and cultural stability of their nations to attain a toxic ethnic nostalgia.

Written in 1936, Iranian novelist Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl stands as one of the classics of 20th century Iranian literature and a powerful depiction of the formless rage that can precede politics. It contends with similar crises of personality and ideology as Notes from Underground, but it is more in the vein of the intoxicated visions of De Quincey and Rimbaud than is Dostoevsky’s narrative. The narrator of The Blind Owl spends the novel in visionary agony. His struggles are manifold, but his principal themes are innocence, transgression, and the impossibility of escape. He takes solace in the lost innocence he may have never had and flirts with transgression by painting pen cases with the image of an unseemly seeming old man and a beautiful girl. In it, the girl is handing the man a blue flower (a morning glory) and the man’s biting one of his fingernails. The illustration sets up a dynamic between an extremely sensitive and tormented illustrator and his almost total alienation from the outside world.

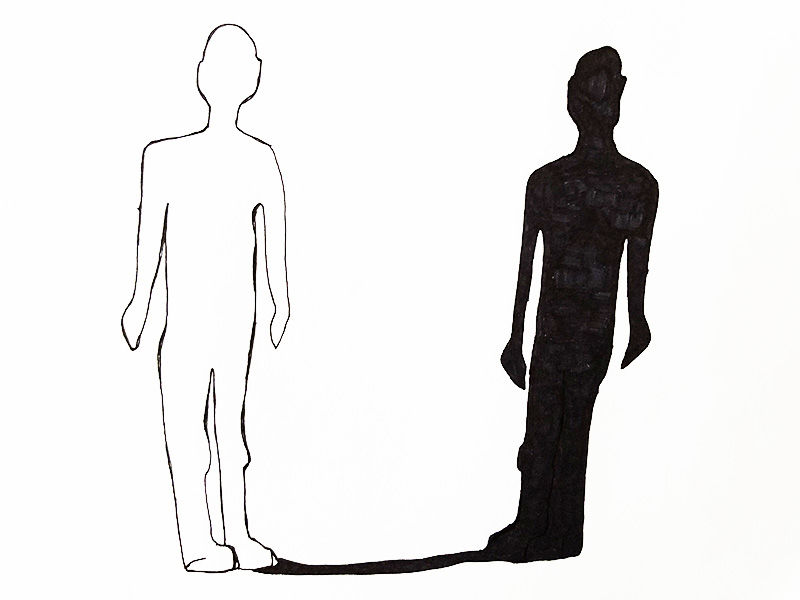

The narrator of The Blind Owl is just as alienated from the outside world as the Underground Man. He feels very little need to seek the world’s empty, futile assurances, knowing, like Dostoevsky’s precarious minion, the weaknesses of rationalism are already obvious to anyone not willfully ignorant. In fact, Hedayat’s narrator connects a desire for self-knowledge to alienation from others, confessing that “ever since I broke my last ties which held me to the rest of mankind, my one desire was to attain a better knowledge of myself.” But there’s a catch: his shadow. Sometimes addressing the shadow on his wall, he likens himself to it, seeking to discern his true character or lack thereof in it. He proclaims “I am writing only for my shadow, which is now stretched across the wall in the light of the lamp. I must make myself known to it.” The futility of the venture is plain, but what else can he do? The venal world of lust, greed, stupidity, and aggression is drooling just outside his door, and he cannot endure even the thought of it. All that’s left is to struggle against the impossibility of himself.

And Hedayat’s novel pushes the bounds of narration to a point where not only is the narrator unreliable, but his shifting terrain, consciousness, and motives become a melange of hallucinogenic despair stunningly difficult to fathom. But that’s the point, after all. Despair on this level cannot afford to be rendered through traditional narrative means. Hedayat’s narrator is like if Kafka, Lautreamont, and Baudelaire all tutored a precocious young artist and that artist was essentially housebound and sexually frustrated. His narrative is a surreal, claustrophobic desire for the shadow cast so elusively on the wall.

He speaks of the “overmastering need” to connect his thoughts to his shadow, “the unsubstantial self”. To compound the difficulty, he is composed genetically of two conflicting forces. His father is an ordinary man of the world, but his mother, Bugam Dasi, is an entrancing dancer, reputed to be a part of the Lingam cult of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction. The narrator clearly takes after his mother. Like Shiva, through destruction, through the rapturous storming of limitation, he creates. But his mother is long gone from his life and all that remains from her is a gift of “deep red wine” laced with cobra venom she gave him as a gift to be used some day when necessity commands. Always, the shadow on the wall.

The narrator’s preoccupation is the impossibility of escape, but it’s also the need for a conclusive end. And the same pre-political formless rage that animates so many anti-rationalists today compels the narrator of The Blind Owl to cast about for a way out of his predicament. Similarly, Maurice Blanchot, in The Work of Fire, relates how Kafka felt writing was an imperative because it was paradoxically an active engagement with and disengagement from the world. Blanchot goes to the heart of the matter, declaring “to write is to take on the impossibility of writing, it is, like the sky, to be silent . . . to write is to name silence.” Writing for Kafka, Blanchot says, was “not a matter of aesthetics; he did not have the creation of a valid literary work in mind, but his salvation, the accomplishment of the message in his life.”

But the narrator’s problem is a problem bigger than considerations of style; words are the fodder in his struggle against contingency and in pursuit of the “unsubstantial self” cast in shadow on his wall. We never can know death, only the endless possibility of death, and Hedayat’s narrator, it seems, suffers from what Blanchot describes as Kafka’s condition, where “existence is interminable, it is nothing but an indeterminacy; we do not know if we are excluded from it (which is why we seek vainly in it for something solid to hold onto) or whether we are forever imprisoned in it.” But unlike Kafka’s ominous but detached narrators, the narrator of The Blind Owl can’t establish any edifice of sublime irony.

In addressing the shadow again, the narrator continues on with disarming bluntness, he holds “a story is only an outlet for frustrated aspirations, for aspirations which the storyteller conceives in accordance with a limited stock of spiritual resources inherited from previous generations.” I know. You want more. The story should be a portal, a guide, a revelation, except maybe it isn’t and maybe it can’t be. Maybe it’s only groan, stored away for years because nobody cares, and diminishing all the while. Which isn’t to say it’s not deeply important to write that story; it’s just equally likely it isn’t.

He’s so deep in his own tortured vision, in fact, he can’t seem to see for very long the larger economic forces behind what he despises, except in the crudest terms. But there are many moments of wicked dismantling. “Rabble men,” he says in one of those moments, redolent of alienation and rage, “hurried by, an expression of greed on their faces, in pursuit of money and sexual satisfaction. I had no need to see them since any one of them was a sample of the lot. Each and every one of them consisted only of a mouth and a wad of guts hanging from it, the whole terminating in a set of genitals.” Like the Underground Man, he connects the pursuit of profit not with enlightened self-interest, but with animalistic hedonism and selfishness. But whereas the Underground Man scoffs maybe too vigorously at the hollowness of rationality and the self-indulgence it sanctions, the reaction of the narrator of The Blind Owl is more personal. It’s all just too visceral and pointless for him to endure.

Like the Underground Man, the narrator of The Blind Owl lacks an overt political program, but he shares one regrettable flaw with many anti-rationalist types today: overt misogyny. He’s disturbingly obsessed with his wife, someone to whom he refers throughout the novel alternately as “the bitch” or “bitch wife.” It’s a jarring, gross element that is, of course, immediately offensive but also gums up the flow of the narrative.

Sexual frustration is clearly an impediment for Hedayat’s narrator. And many of Donald Trump’s virulent supporters have a track record of misogyny too, and obviously for them sexual insecurity looms large. Abi Wilkinson has been visiting the fetid corners of the internet where so many of these angry men dwell for a while. In a November 2016 piece for The Guardian, she tells of her visits to “the loose networks of blogs, forums, subreddits, and alternative media publications colloquially known as the ‘manosphere,’” which she describes as “centered around hatred, anger, and resentment of feminism specifically, and women more broadly.” This so-called “manosphere” makes up a significant part of the far right and often neofascist internet culture broadly called the “alt-right.” But more importantly, there does seem to be an (almost always white male) type attracted to these communities. Wilkinson has found they “skew younger on average,” but they’re “drawn from all walks of life. There are socially awkward, video-game loving teenagers, bitter divorcees, and Ivy League-educated Millennials who feel women don’t afford them the respect and admiration they deserve.” Here, the rational premise of women’s empowerment and equality is a threat to fragile masculinity. The irrational response of so many of these admirers of Donald Trump is hardly surprising, considering the president’s dismal record with regard to women and his limited capacity for entertaining, let alone tolerating, rational premises.

But the narrator of The Blind Owl takes his misogyny to a whole new level when he sets out to finally stab his wife to death. He has pangs of conscience along the way, even calling it off at one point. But his formless rage relentlessly drives him forward. This time, though, his wife sexually embraces him and he gives himself over. His dual revulsion and lust makes clear his desire to overcome his sexual anxiety, to calm the tempest of his wooly, wild mind. When he does give in, he realizes his passion and his nightmare. “Every atom in my burning body drank in that warmth,” he says. “I felt that I was her prey and she was drawing me into herself. I was filled with mingled terror and delight. Her mouth was bitter to the taste, like the stub-end of a cucumber. Under the pleasant pressure of her embrace, I streamed with sweat. I was beside myself with passion.”

Throughout, he’s still holding the knife he was going to use to kill her. Right after he feels the flesh of their bodies “soldered into one,” he “involuntarily” stabs her and kills her. The transgressive imperative in him explodes and he breaks into laughter, “a laugh so deep,” he says, “that it was impossible to guess from what remote access of the body it proceeded, a hollow laugh which came from somewhere deep down in my body and merely echoed in my throat. I had become the old odds-and-ends man.” The lure of transgression and the impossible selfhood he seeks, turn out to be, in the end, tantamount to the venal indulgence of those like “the old odds-and-ends man” and other buying and selling types he so deeply despises.

So he’s left a vile criminal, and, all the while, a visionary addressing himself to the shadow on the wall. He tells the story because it has to be told, whether it’s possible or not. He tells the story because he must fulminate against, consciously or not, rationalism and the greed and venality it sanctions. But he does so in tragic obscurity. The 20th century rise of fascism and its resurgence in various forms in the West today demonstrates the potency and peril of formless rage seeking expression. If that rage takes the form of ideology, it can lead us deep into a vacuum of irrationality where an authoritarian inevitably rises and remakes reality for the rest of us. Then the abyss opens wide, you’re in it, and there’s nothing else outside or in. You can try to write your way out. You can try. But you might have to take your work underground. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.