The Meanings of J. Robert Oppenheimer is an entry in the Iowa Series in Contemporary Literature and Culture. I was drawn to it because I am drawn to all things Oppenheimer. I was not prepared for the approach the author, Lindsey Michael Banco, takes, which might be likened to a statement exponentially increased since it is not so much a portrait of Oppenheimer as a series of portraits of Oppenheimer, not so much history as a history of history. Banco himself declares that “the book explores the workings of Oppenheimer as a ‘principal metaphor.’” In the course of this book, we are reminded of the uses that have been made of Oppenheimer as a central image, the ways in which books, movies, television shows, museums, his own writings, and even children’s books have presented him in relation to his personal history, the Manhattan Project, WWII, technology, science, literature, and visual art. If you have not yet read one of the standard and solid histories about The Manhattan Project and Oppenheimer’s role in it, this is not the book for you. But if you have, you will find it fascinating. (I did.)

Read It

The Meanings of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Lindsey Michael Banco

Fascinating, if not always easy to grasp. Banco writes out of an understanding of Oppenheimer as “a central organizing principle in thinking about atomic bombs and postwar nuclear culture.” He characterizes Oppenheimer’s speech as “typically convoluted syntax” but nevertheless (and, I think, rightly), praises Oppenheimer as an icon of “presence and humanity.” Banco describes his own book “as something of a demystification project.” The figure of Oppenheimer (whether simultaneously or now and again) exposes the possibilities of both apocalyptic ruination and the at-least-for-the-nonce salvation of technology. Of course, that figure changes over time. There is an Oppenheimer for then and now, an Oppenheimer for here and there. There will undoubtedly be Oppenheimers for the future. Or maybe not, but I hope so, because he is endlessly interesting, as the very existence of this particular book demonstrates. As Banco puts it, “Oppenheimer is a cultural cipher with many, often contradictory, meanings.”

Banco mentions wave-particle duality while suggesting Oppenheimer is the locus of numerous dualities. I venture to say that all or most of us contain contradictions, although most of us are not viewed through a prism of fame, and, of course, most of us have never wanted, or been asked, to build a bomb. He volunteers a note on his strategy:

My approach to tackling the bomb’s resonances is to focus on a series of conceptual oscillations, arguing that such oscillations are both integral to understanding the moral, political, and cultural status of the bomb and reflective of the constant historical oscillations between support for and apprehension about nuclear weapons, between a spirited activism and a curious apathy concerning these devices.

I am somewhat surprised that Banco does not refer to Niels Bohr’s complementarity principle, which advises us to remember that, pretty much everywhere, a thing may be considered in terms of contradictory properties. If we look at a wave, we cannot see that particles are headed our way, and vice versa. This principle has slipped into philosophy, where it cautions us to look around at the astonishing more that is always attached to what’s there.

But Banco’s book is an invigorating and informative take on Oppenheimer studies. The notes at the end are plentiful and lead us to other books about Oppenheimer. Despite its nature as an academic book, Banco’s writing is clear and often enlightening and teaches us to think about nuclear developments in detail and broadly, as we should. As we must. •

Kelly Cherry’s Oppenheimer book comes out February 2017 from LSU Press.

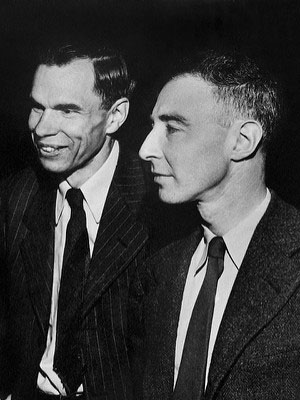

Feature image courtesy of Berkeley Lab via Flickr (Creative Commons)