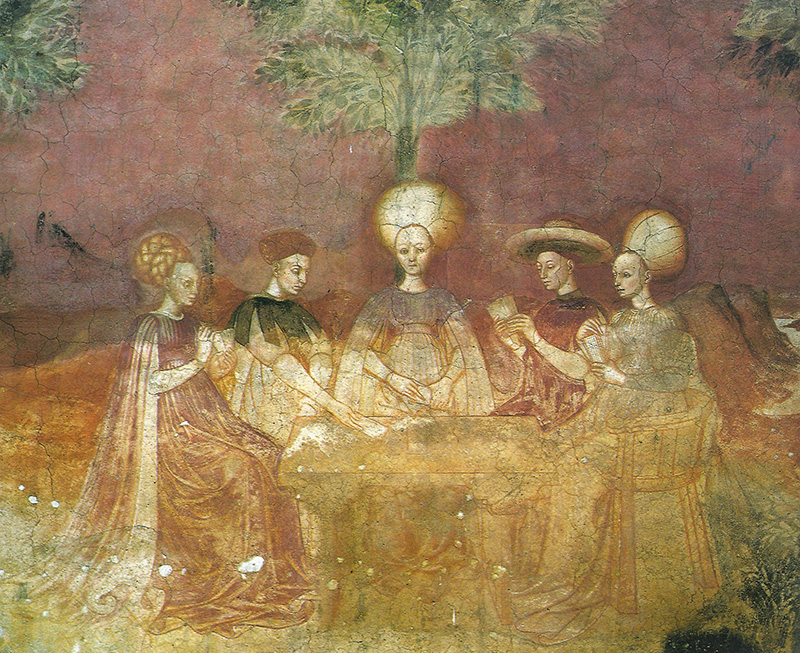

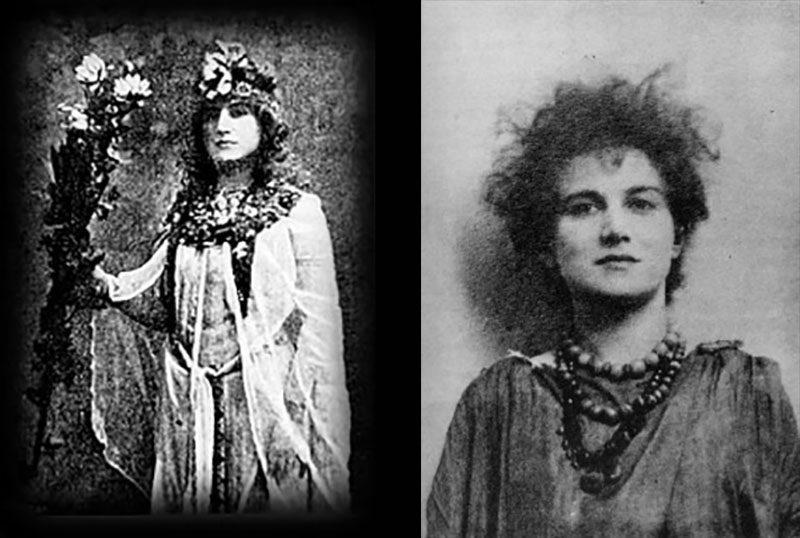

Although it’s the men of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn we associate with the magical order, specifically the great poet and mystic W.B. Yeats and the sociopath and con man Aleister Crowley, women were fundamental to its running from the very beginning. Unlike the Christian churches they mostly came from, either Catholic or Protestant, women were allowed to be priestesses, allowed to write doctrine, allowed to design ceremonies. Not only allowed, but simply did. For these independent-minded late-19th-century and early-20th-century women, moving from the dominant religion to a religion of the occult and mystical moved them from subordination into power.

The rise of the Golden Dawn, and Spiritualism in the United States, came at a troubled time. There was widespread poverty, a rigid patriarchal system, disease, and high mortality rates in children. With so much instability, it was difficult for many to simply live their lives with dignity. Alcohol consumption was high, domestic violence was treated casually, and many died young. In such times, it can be difficult to imagine how to get through tomorrow, let alone how to envision a better future.

As Golden Dawn teacher and leader Florence Farr wrote in her 1910 book The Modern Woman: Her Intentions:

Life seems hopeless to the middle-aged. Most of them once thought they could put it right in a week if they had a free hand. They try, they fail, they marry and spend the evening of their lives trying to destroy the illusions of their children as quickly as possible, so that they also may ‘settle down’ to hard facts. To excuse himself a thinker will say, ‘I know the dangers of cultivating the imagination; I know that unless it is nipped in the bud this wild flower of the mind will twine its tendrils round me, cover me with its shadows, intoxicate me with its fragrance, and destroy reason and physical health.’

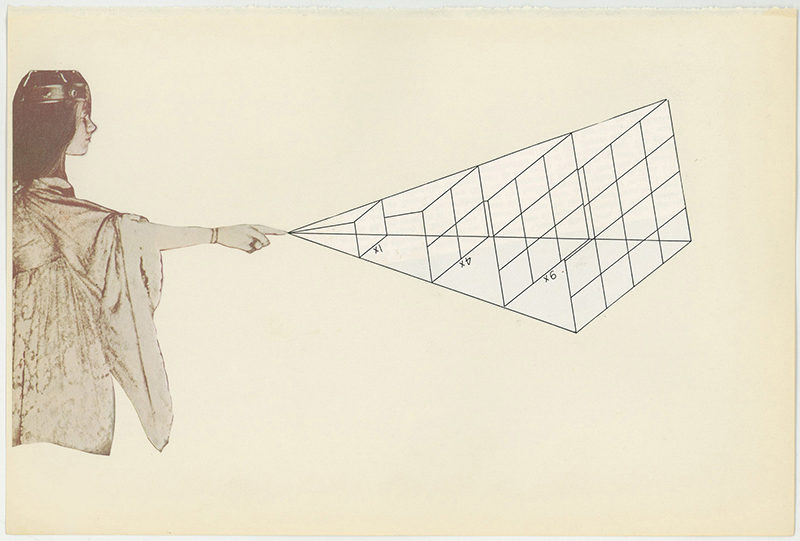

And yet the imagination is key to social reform and revolution. In order to figure out how to make things better, one has to envision a future where things are better. But if one is always managing your disappointment, refusing to hope so as to avoid being let down, then only hopelessness and helplessness remains.

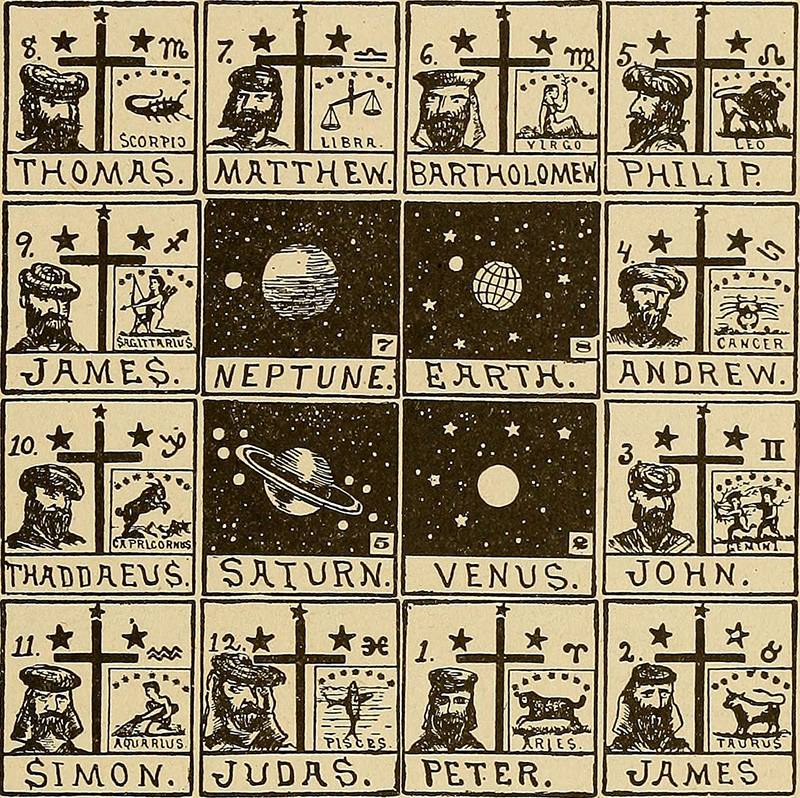

The Golden Dawn (and Spiritualism) fostered women’s rights activists, activists against poverty, educators, anti-colonial revolutionaries, and radicals of all stripes. And the way they broke through the despair of daily life was through magic. The Golden Dawn magical system is and was a way of communicating with the spirit realm or with the unconscious, divining the future through tarot or astrology, raising certain energies, and so on. At the heart of magical belief is the belief in your own free will, in your ability to make changes and influence the world. It wasn’t accepting your circumstances, it was working to understand and directly change them.

And of course, they were seen, and are still seen, as nutcases. Yet, important books were published, movements formed and influenced, social change wrought by these nutcases. And as our society is in another dark place, with nationalism, racism, and misogyny on the rise and little imagination about how to change things on display, perhaps it’s time to look at what magical thinking actually does for a person.

•

Ernesto de Martino was an Italian historian and anthropologist who died in 1965. His works, which focused primarily on religion and the supernatural in Italy, have only recently started to be translated into English. His latest volume to find publication in America is the 1959 study, Magic: A Theory from the South. Studying the use of magic among the people of Naples and the surrounding areas in the 1950s, he finds that what most believe should have died out in the wake of the Enlightenment is not only still in use but has a productive component.

De Martino finds love spells, spells for the protection against the evil eye, spells to keep breast milk from drying up, spells to dispel storms and bad weather, spells to get rid of headaches and stomach pains. If you want someone to fall in love with you, you mix your blood with pubic hairs and hairs from the armpits, you dry it in the oven and during Mass you hold the mixture aloft so that it is consecrated. If a child has been sick and losing weight, a mother prepares a bath of water that pasta has been boiled in and three pinches of salt and bathes him at sundown. If you are tormented by a masciara, which is something like a succubus, you grab onto their hair and hold onto them until dawn, praying for the strength needed.

But then there are smaller versions of magic, something like superstition, where it’s not so much ritual as just awareness. If you’re pregnant, you don’t burn certain woods in the fire for fear it will give your child a bad complexion. You do certain things to ensure your baby’s health, you do other things to prevent miscarriage or bad health. If you do the wrong thing, like tying a knot that might cause the umbilical cord to wrap to wrap around your baby’s throat, there are simple things to do to undo the potential damage.

All of which is performed to give the person the feeling they have some control over their lives. As de Martino writes, “One might say that the root of. . . magic, is the immense power of the negative throughout an individual’s lifetime, with its trail of traumas, checks, frustrations, and corresponding restrictedness and fragility of the positive.”

What trauma does, according to de Martino, what loneliness or lovesickness does, what illness, what fear does to a person is remove them from their own life. It causes a “crisis of presence,” as he calls it. If you are sick or damaged in some way, you cannot work, you cannot take care of your family, you cannot participate in your community. You are not able to be present for your own life. Instead, you are off in the margins, watching the world go by, unable to figure out how to rejoin.

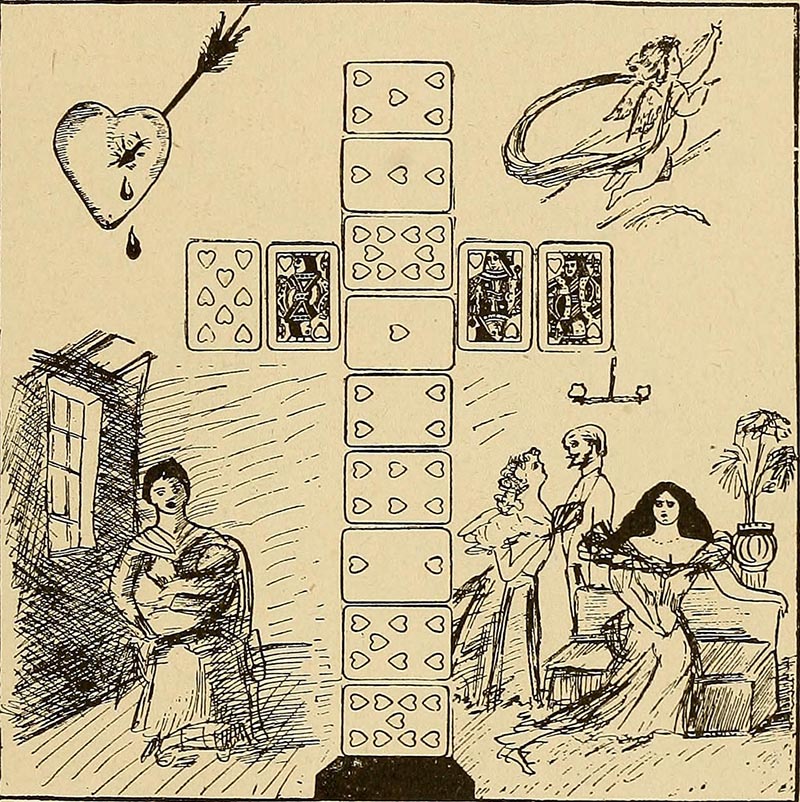

Magic, then, is a ritual for returning yourself to your life. If you are in love, and it is not returned, slipping your menstrual blood into his coffee in the hopes that will bind him to you eternally is at the very least something to do. It shoots off a little light into the future and gives you a reason to walk forward to meet it. Rather than feeling hopeless, believing there is nothing to be done, so why bother doing anything at all.

The body responds to placebo. We don’t know why, but it does. In many studies, taking a placebo pill is as effective as an actual anti-depressant and anti-anxiety medication. Placebos can also be used to treat hormonal problems like menstrual troubles and menopause, chronic pain, sleep disorders, and digestive issues. A new study suggests that even if you know you are taking a placebo, there is some health benefit for the patient.

Which is not to say that magic and ritual is just a placebo, but that the human body and mind are mysterious, and our understanding of them slippery. And if the goal is to reintegrate the marginalized soul back into their life and society, perhaps magical thinking is more effective than rational.

De Martino noted that love magic was more likely to be practiced by women. That was not, he cautioned, because women are more irrational or fanciful, as is often claimed. He believed it was because women have far less free will in the areas of the world he studied. If they fall in love, they have very little agency, as it is men who court and men who propose marriage. So rather than remaining passive and helpless, love magic gives them agency and allows them to participate in their own lives. Whether or not magic “works” is the wrong question. It’s whether it allows the magician to work that we should care about.

•

“The choice between ‘magic’ and ‘rationality’ is one of the great themes that gave rise of modern civilization,” de Martino wrote. And yet it seems this is less of a choice than a spectrum that we slide around on a daily basis.

The women of the Golden Dawn were a bit like the lovestruck teenage girls in Southern Italy de Martino wrote about, unable to fully participate in their lives due to lack of agency. But practicing magic taught them how that agency was being stolen from them by the limitations of British society, and laws that kept them in terrible marriage, kept them from owning property, kept them trapped in hierarchies based on class, race, and sex. Magic taught them to fight back.

“The ambiguity arises when we judge magic on the same level as modern science and with respect to the same objectives,” de Martino wrote. We expect magic to do the heavy lifting, rather than realizing it is magic that allows for the heavy lifting to be done. Florence Farr and her compatriots did not stop at magical practice. They did not cast spells for women’s suffrage or for oppressive laws to be overturned. They wrote books, they campaigned, they gave speeches. De Martino continues:

“It follows that no human civilization has ever based itself exclusively on such [magical] attitudes, since civilization is the ethos of man rising up as a rationalizing presence in the heart of naturalness and establishing himself as an autonomous person, present to himself as to the world . . . Thus we are not denying that a magical practice can, for example, facilitate a hunting party’s good results, but no civilization could give up on actually hunting: the hunters of the Paleolithic never simply opted for magical drawings of animals with arrows piercing their bodies.” •

Images courtesy of Sigo Paolini, Internet Archive of Book Images, and Emily Dunne via Flickr (Creative Commons). Unknown, Hermetic Golden Dawn, Telrunya via Wikimedia Commons.