On a humid day in early October, I walked from the Ponte Sisto to the Ponte Mazzini. The river was flowing on my right and the progress of Western European culture, from a Roman point of view, was turning into illustrations on my left. I had been in Rome for three weeks and had briefly seen the illustrations, a range of military and cultural imagery, including generals, a recurring angel, victims and perpetrators of violence, mythological agents, and occasionally the general populace. But now I was set to walk the half-kilometer extent of William Kentridge’s monumental set of drawings and parse as best as I could what these 80 figures spelled out. The title, Triumphs and Laments, gave a broad context, and for an admirer of Kentridge’s work, this was a veritable feast. Along with such admiration, there were bound to be questions of technique, archival recovery, historical meanings, and artistic daring.

Here, at the very least, was a work of public art like no other. One commentator called it the largest public work of art in Rome since the painting of the Sistine Chapel. Thankfully, there weren’t the teeming inattentive crowds that today make a visit to the Sistine Chapel such an ordeal. Few people were watching the Kentridge, especially if we discount the bike riders and joggers that use the newly paved walkway, itself a result of civic efforts to draw attention to the generally dreary, large-scale banks of the famous river. Now a portion of the river has become a model of urban restoration and the disregarded river banks turned into a worthy site for visitors and citizens. Here the plein air setting meant the city and the historical river lay open to easy view, as the black and white illustrations were as large as the stone walls that serve as Rome’s flood control barriers. The technique employed by Kentridge, which produces the effect of each image having been drawn with a giant charcoal stick, has been called “reverse graffiti”: an offbeat term for an elaborate process.

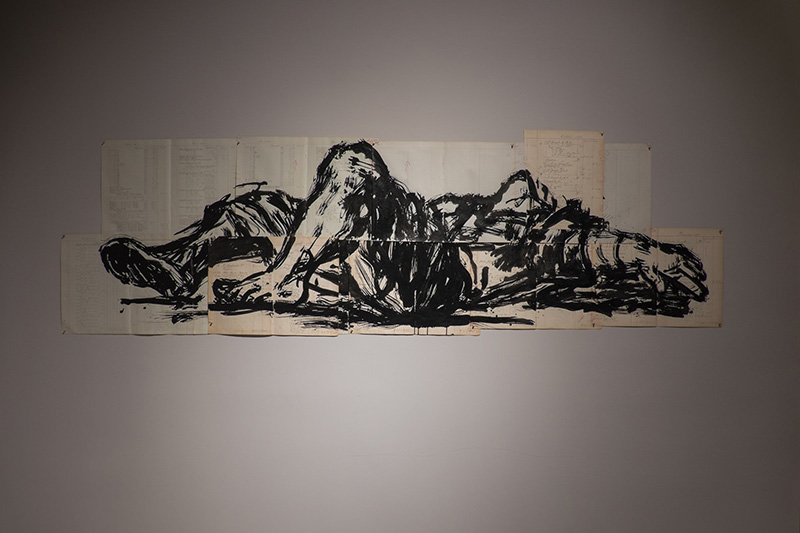

Here’s a brief explanation of how it was done. Kentridge began by drawing his subjects with charcoal on large sheets of white paper. Then, a reverse stencil was made of each drawing. One by one the stencils were held up against the soot-blackened stones of the flood control walls. Then a spray was shot against the walls, thus removing all the soot and leaving behind the “imprint” of the stencil. The contrast between the soot that remained — protected from the cleansing blast by the material of the stencil — and the newly whitened stone resembled a giant charcoal drawing. From bearing dark deposits to showing shapely lines, the walls turned from bearers of waste to elegant works of graphic art.

The use of Roman motifs in a processional array seems an inevitable choice of subject matter given the location of the piece. Even the use of graffiti rings out as inevitable since much of what we know about daily life in Rome comes from the hundreds or thousands of examples of graffiti that mark the stones of the city. So the archival process of re-imagining begins by being bounded by a logic: from the low material of graffiti to the high content of historical meanings in Roman history. Public art begins, of course, with statuary and plaques in full public view. This branch of art delves into the questions of power and memory, as the word “monumental” (remaining in the mind) reminds us. But Kentridge uses history for other than a celebratory exercise. His view of history is mordant, whether he’s considering Rome or his native South Africa. The medium of “reverse graffiti” recalls the needed and consistent return of common belief, even vulgarity, in which the vox populi has for the moment taken the stage, shoving aside the triumphal victory speeches in favor of the lamentation and outrages of the forgotten citizens.

•

Most public art imbued with a civic consciousness envisions its meaning with the use of archival recovery. Anything that is celebrated in such a context must have already passed into history. If built too soon, the monument may well end up looking like an act of vanity; built too late, the impact appears to be the pursuit of a mere antiquarianism. Roman history avoids this dilemma by being in many ways so overly historicized that it is always ancient and always new. The epithet of “the Eternal City” catches this perfectly. Kentridge works with such points constantly in mind. The very texture of his images — stark yet softened by age — suggests a veneer of the authentically historical and that texture surfaces in the sense of his belief in the notion of what some call “historical action at a distance.” The simplest example of this is the way ancient models of government action, values, and institutions survive today even “inside the beltway,” where the American Congress keeps alive (or tries to) the idea of the Senate, a body designed for deliberative reasoning as practice by the most high-minded civic figures.

Of course, our Senate is no more capable of fulfilling its highest ideals on a regular basis than was the Roman Senate. The gap between high purpose and craven calculation is written largely in Kentridge’s picture-making. Often figures appear to fall or be toppled; horses and wolves are shown as skeletons of themselves: Nothing looks quite regal or imperial except the wagons of booty brought home from Rome’s imperious campaigns. Here, too, the use of graffiti as his medium encourages Kentridge to be uniform in his style even as his range of historical imagination — its periods and figures and tropes — achieves an extensiveness which can only be called Roman. The grit of the prototype of all empires is there for everyone to see, and underneath its range and order, like its road system and its cloaca maxima, there is an interconnectedness that links the highest and the lowest.

Just what can be made of Kentridge’s views of history remains a puzzle. As with all people who think seriously about history will attest, its complexity is a steep challenge to epistemological clarity or logical rigor. The best thought on the subject is probably Nietzsche’s essay on “The Use and Abuse of History,” which sorts out different ways that history gets “applied” in attempts to clarify events and how we estimate their importance. There is also the cynical definition, often attributed to A. J. Toynbee, which sees history defined as “one damn thing after another.” Sequentiality conquers consequentiality. By choosing Rome and its long tradition of history and historical meaning, Kentridge implicitly signals that he knows how impressive high ideals can be. Even if they don’t always determine the winners and the losers, the triumphs and the laments, they give shape to the narrative that history must convincingly construct if it is to have a place in the meaning and values of human lives.

The installation on the banks of the Tiber begins with an angel who holds a tablet on which she is writing (or drawing?) the events that follow her. I suspect the angel is taken from an essay on history by Walter Benjamin, the German critic and cultural theoretician. Benjamin imagines that the recording angel has her back turned to the direction in which history is moving. Her pose allows her to see the detritus of history and human strivings as they accumulate. This means history can only be parsed, if at all, after the destructive forces have played out and left behind the heaped remains of everything the species has sought, all of which bear — but in fragmentary form — the glimpses of those values and desires that drove the storm that dismantled them. The angel reappears later in the sequence, and at last, is seen tumbling to the ground. Has the story become too complex, or too repetitious, to be recorded, even by the angel? The weight of history, to use an ages-old figure, may be, in Kentridge’s view, not only something tragic heroes bear individually but is rather too much for all of us.

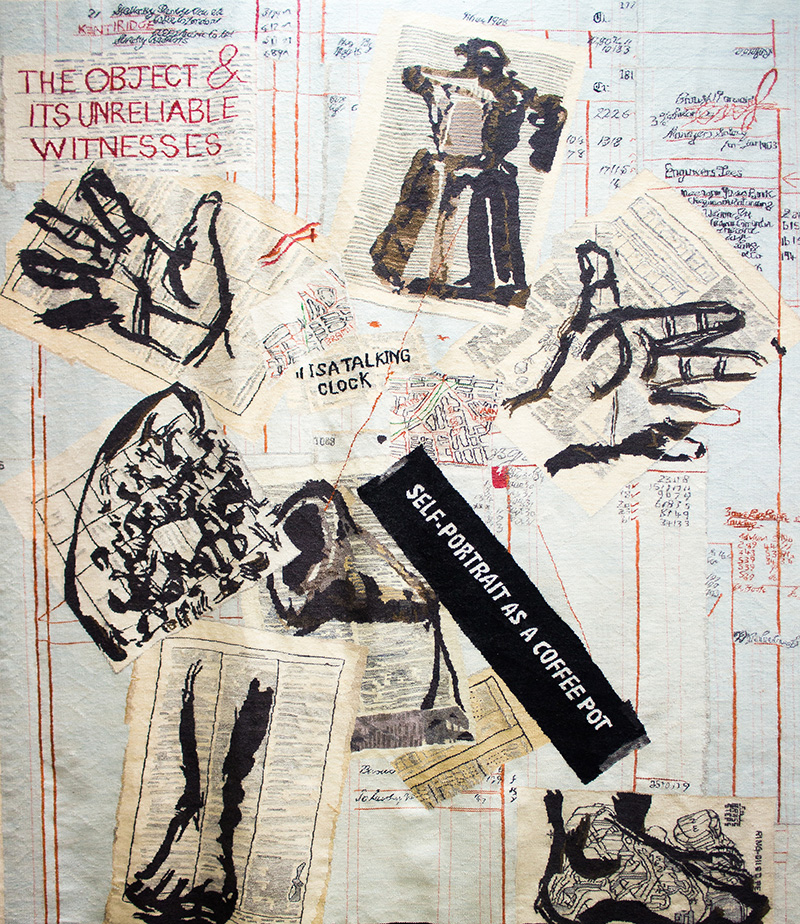

Kentridge responds to such probable defeatism and cynicism with artistic daring. For some time now he has been one of the most admired and applauded contemporary artists. His reputation relies on many aspects, but chief among them is his bold use of different media in ways that break the usual barriers. He is perhaps first and last a draftsman, with a distinctive “hand” and a cunning use of repeated motifs. But he has also used film, installation art, ethnographic and archival subject matter, traditions that rely on stagecraft, and abstruse narratives. This was clearly evident ten years ago in his impressive installation piece, Black Box/Chambre Noir which, in multi-media fashion, dealt chiefly with Germany’s imperialist project in Africa and the predations brought about in the name of the white man’s burden. (I discussed some of this in my essay on Kentridge in Salmagundi, Number 152, Fall 2006. But the critical literature is already immense.) Transferring his graphic vision to the walls along the Tiber would be utterly daunting to most artists, but Kentridge has done it in a manner not only respectful of civic values but with a brio and confidence that is familiar in Rome’s artistic history.

His daring is also evident in his approach — one might almost say his attack — when choosing his subject matter. As with many contemporary artists of the first rank, Kentridge is quick to combine the high and the low, mistrustful as he is of too much facility. (One sense in Kentridge’s comments on his own work that glibness is always the enemy.) Two examples out of the 80 may suffice to illustrate some of his sensibility.

First, there are the two appearances of a papal figure in the procession. The first instance shows the pope moving forward as if climbing stairs or fleeing from some threat. This could allude to the time when Clement VII had to flee through the underground tunnel that links the Vatican to Castel Sant’Angelo in order to escape French soldiers during the sack of Rome in 1527. The history of Rome cannot be told without the history of the papacy. Choosing this episode to stand in for the interwoven histories shows how Kentridge sees the split between secular and spiritual powers as one of art’s major recurring themes. The pope is also depicted in the very next figure behind the running pope. But here he is seen as lying in a cart being pushed by two workmen. It could be the pope himself is viewable as building materials since the careers of so many in the line of papal succession have spent millions on large monumental churches and other works of homage to their own supposed munificence.

The second-to-last image provides another instance of Kentridge’s imagination at work on history and its many cunning corridors. It shows two people, a man and a woman, facing one another closely, standing in a bathtub. Above the couple, a showerhead rains down the water that fills the tub. A closer look reveals the historical personages being portrayed here: they are Marcello Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg. The scene obviously parodies the famous moment in the Trevi fountain from Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and allows Kentridge to record how the concept of “heroic historic exploits” has been transformed into “icons of popular culture.”

We might consider that all our triumphs and laments end in a moment of popular entertainment, and this surely spells the end of any glorious march of history. Indeed, some may see it as a final boundary, the time when the river of history is constrained by a blank wall or enters a vast and empty ocean. The time still flows, however, down to the sea between Ponte Mazzini, the astute politician who helped form Italy as a nation state, and the papal echoes of the Ponte Sisto, named after Sixtus IV, the generous pope.

So, for some waggish viewers, all is not lost. Kentridge has taken care to show that the tub has wheels on it. History can still move forward after all. •

Images courtesy of See-ming Lee, Darren and Brad, Sandro Lombardo, Bruno via Flickr (Creative Commons)