I read Sumana and remember my longing for you, to you, as a tree.

The Lade Braes is a kind meandering walk that twists itself, like an apology, through the heart of Saint Andrews in Scotland. As I trudge through, the trees breathe with the breeze, with me, with the cold, the stream speaks and whispers, and the sun glints past an imposing yet generous canopy in Boase Wood. My response to them is a curious whisper to match, a series of questions read, hushed, from Sumana Roy’s How I Became a Tree. The book, termed an “an ode to all that is unnoticed, ill, neglected, and yet resilient,” is a set of essays that grapple with the gendered (dis)embodiment, (a)temporality, and cultural significance of plant life. In each chapter, Sumana traverses the boundaries between the personal and political, individual and ecological, grounding her stories in an environment of growth, playful discovery, and care.

I begin with a curious question, an almost childish one: “What was the scope of making mistakes in the emotional economy of a tree’s life?” The leaves chatter back an immediate rustle, almost admonishing; I’m curious, do they mean to say they make mistakes all the time, or is there no room for error or eroticism in the aesthetics of flora? Training myself to walk slower, to take gentler footsteps, and to feel the shifting textures of the moist earth, I pass trees that mimic the seasons — the calm maroon rage, the many pluralisms of green, and the memory of yellow in the autumn woods.

In her book, Sumana reflects upon what it means to not simply be a tree, but the process of becoming one — to sense time, feel intimacy, (un)know gender, process grief, and find death (and rebirth) like a tree. Like Sumana, I too secretly wish that by mimicking slowness, stillness, I too can become one of them. That by rooting myself to trees I can reserve a quickly dissipating memory, greedily collecting the light. A present moment that is, as per Anuk Arudpragasam, “eternally before us, one of the few things in life from which we cannot be parted.” I would like this memory to remain eternally present; but my heart disapproves, clutching firmly to the past. Presence requires patience and clarity, a grounding of thought in the soil, the earth. Yet my mind flutters with the bird drinking from the stream, reminding me that I am neither still or flowing, but pregnant and heavy with this specter of loss. For the grieving, grief is the only present.

In reparation, to unbetray my new sylvan friends, to beg forgiveness from naked branches that were once a shade of a welcome embrace but now seem scorned, accusatory fingers and questioning gazes, I idle my thoughts of you and think instead of green. There are no policemen here, but that doesn’t stop me policing myself away from you, from this perduring longing. My body is neither weaker nor stronger but has become more yours than mine: I’ve inherited your; enlarged liver, your sartorial kindnesses, your fleeting weaknesses, and brave humors. I feel my jaw clicking when it’s quiet and within our anachronistic hypochondria I find solace — sickness, for once, is not personal but communal, a sharing that is melancholia and security at once, a pandemic of solidarity.

The trees at Lade Braes agree, their plagues are often shared too, and their separations aren’t as distinct. I remember when you packed my bags for me when I couldn’t leave home, when I asked each time if this would be the last I ever saw you, and one day, I was right. But you’re still here. And now, I challenge the nature of departure and the departure of nature.

Do trees know departure? Do their loved ones leave, do they feel heartbreak as spores dissipate, as pollen travels, as seeds float away? Do they mourn their leaves each fall, or do they fall because they mourn? Or, perhaps, is it unnoticeable, and the trees have no gaze, do the leaves fall like our skin sheds, daily but in tree time, Sumana’s tree time that lives in the present, “a life without worries for the future or regret for the past?” I note here her words: ‘worries’ for the future, yet a singular ‘regret’ for the past, the pluralism of eventuality — the solid singularity of an unchangeable written history. I think that maybe we have it wrong. Maybe summer is their mourning, a longing of reaching, stretching greedily towards an unattainable sun, basking in whatever light they’re spared before, resting, drooping in moonshine? Maybe they, like some poets, know that the moon could love us, but never nourish us. If it did, truly, who would write the poetry?

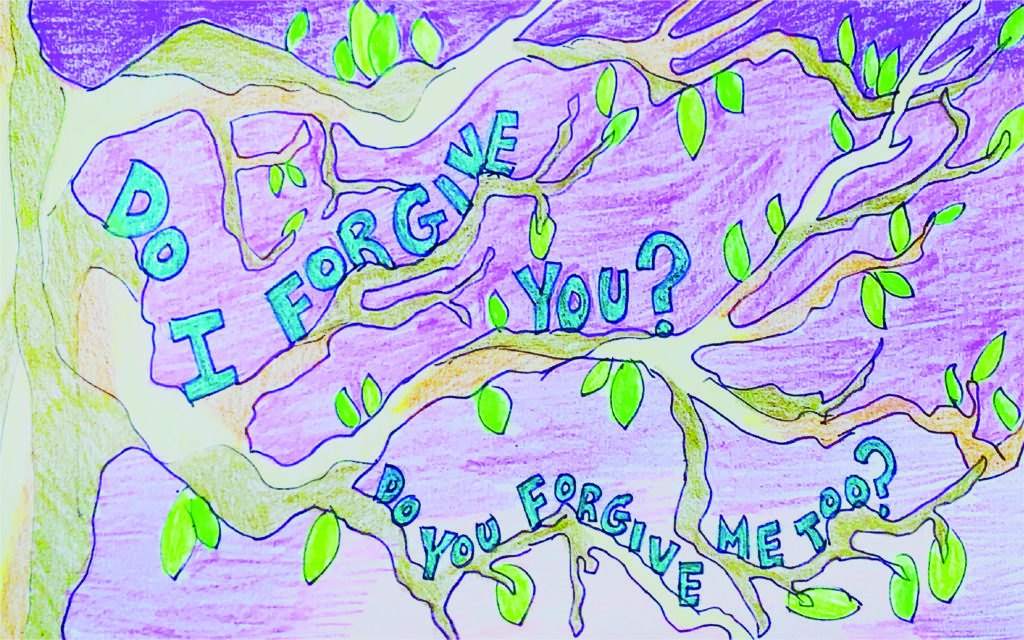

The poetry of trees is, after all, about agency — the act of breaking, rending, repairing, citing through metaphor. But what agency do trees hold? When I yearn for your presence, your lap, or the softness of your palm, I hold responsibility — I am aware that it is my incapacity, my impotence, my stuckness, and my grief that binds me here and draws my heart to your absence. I possess it, and it is mine. But the trees of Lade Braes hold no ownership, nor do they make claims of responsibility. They care without favor or fault and should a plant wilt or die it’s rarely of their own doing. It’s the soil, their water, their sunlight, the environment, the surrounding greens, a disease, an animal. But never them. If I miss you like a tree, do I forgive you — accord your failings to an unquestionable determinism, relinquish any illusions of agency, as if I too don’t reach out to you? Do I pretend, then, that you forgive me too?

As I walk past the bridge near Law Mill, I am led — as the Lade does its water — to ponder its name. A Google search reveals an unearthed etymology; law from hlaw meaning both prehistoric grave and a mound, or a hill, with treasure beneath. Are the bones the treasure? Why are treasures always buried, interred, and where do my ideas of wooden chests buried near oak trees come from? It’s perhaps the same unknown spirit, an old memory (or just a story my mother told me when I was a child), that tasks me with the rigor of sitting by streams as I do here now. Sumana writes that “poets have always seemed to find something under a tree” but the poet in me finds only myself here, clothed in a regret — that I cannot drown myself in the water to become the river.

This makes me giggle — at our shared love for Bruce Lee’s “be water, my friend,” or blurry greyscale videos of his nunchaku ping-pong games. The more I smile at your void, the more I find myself rooted here firmly in the wet ground, twirling through stone, but also constantly looking up at the trees above, in linear opposition to my daily curvature — the academic’s hunch over a computer, researching and teaching, and longing still. My neck aches and I know, it is not yet a trunk, but a growing branch. I know it yearns and holds, like the trees, at unrest.

Forgiveness too is a question of rooting and branching, remembrance and penance. Hannah Arendt thought forgiveness was “the only way to reverse the irreversible flow of history.” It has its structures and processes, but is also a “loving science”, like Rabindranath Tagore’s love for flowers that Sumana cites. She says that to love a tree “is to be a permanently exiled lover.” Amidst the native trees and the wildflowers here, I know with certainty that I did. Seating myself beneath a pine, I find divergent etymologies; the pine tree from Latin pinus, as opposed to the verb “to pine” which draws from Old English pinian (to suffer, to torment) and Latin poena the mythological spirit of penalty, penance, and punishment (Poena in Roman, Poine in Greek). I sit, pining away, moving closer to the tree as if such proximity would rid me of this exile. Would make me find you like the Japanese myth of the Moeto, couple and the twin pines — lovers whose spirits reside in pine trees, finding form only beneath moonlight.

And so now, I wait for the moon to arrive. The wait isn’t long, for I wait in tree time. The wait isn’t lonely — I sit beneath “a tree, not a forest,” like Sumana’s notes on the Buddha and his Bodhi. The wait is cold, but trees are fine with the cold, so I am too. Here, the rest of the Lade are mere witnesses to my restful friendship with the pine, leaning on its roots, tracing its anatomy which is in every sense the anatomy of a lap, your lap. In its leafy understory, I find your fingers playing with my hair, cautiously casting a “rest of temporary and happy forgetfulness.” Slowly, the streetlamps switch on and dogs, couples, and joggers move past. The Lade grows louder in the dark, more of the whistling, creaking, gossiping buzz of a forest left to its own devices — except of course for the two of us, here. After dark, the moon hides, peaking at us between clouds and branches, a Tagorean lover’s quarrel: “keno megh ashe hridoyo akashe?” (“why do these clouds obscure the sky of my heart?”).

Of course, your face is no longer clear to me, eroded as it were by too much thought, too many dreams, too many imagined impossible returns. I turn to the chapter “The Rebirth of Trees,” where Sumana writes, “Turning into a tree seems a safe enough shelter for the dead who want to remain alive in some way,” conversing with tales of human transformation into trees, as lovers and grievers, and the entrenchment of this transformation in gendered violence. I take from Sumana in not holding myself only to these romanticisms, but to these more unpalatable relations. What violences do I inflict on the pine, reading a book on these roots, on the moss, through this act of seating? This imposition? Have I rid them of sunshine in the Lade, did I rid you of it too on the days I laid my head on your palm? Is there any consent at all in grief, in remembering and thereby keeping alive, in that forgetful rest? And what is it with longing amidst nature that finds space in the vocabulary of ecology — memories of palm-shaped palm trees, pine trees that pine, the fall, the rose, leaves that must always leave?

If I’ve learnt anything at all from the Sumana, from the Lade, and from the longing, it is the wisdom of the question over the answer. I do not wait for replies from the woods — or from you — anymore. I ask for consent to sit beneath the pine tree, but do not expect affirmation. I do not hope for the ableism of voice, but the language of quiet, rediscovering “the silence of death with the vocabulary of silence of plant life.” It is in this silence that we make our home, find our (be)longing. As with all homes, we leave with the hope of return, much as I do now as I close How I Became a Tree. Sumana in the Lade Braes has me speaking the language of silence.

Yet as I stand up to leave, my feet don’t move. They are rooted, they are still; only my hunger uproots them. I trip on a log on my way back up to the paved path, realizing that the hours of looking at the canopy — at yellow-orange leaves drifting in autumn fall, at the spirited moon, and the overcast sky — have left me uncertain about the humility of a careful step. They have rid me of the anxiety of ready eyes constantly trained on the ground. Plant life isn’t afraid to fall, after all, like we are. The floating foliage isn’t concerned of destination, or journey. As I leave, I bid the tree goodbye but not the forest. I depart from the pine which remains resolute and unnerved, unmoved in its home near the water. I leave as a leaf, a tree, book in hand, and you come along with me. The pine stays, and the Lade leaves us, longing. •