On February 1, 2016, the anniversary of Langston Hughes’s 1902 birth, the poet achieved a 21st-century mark of distinction: his name trended on Twitter. Over at the music streaming service Spotify, 8,099 listeners in the past 30 days had played recordings of Hughes reciting his poetry. On YouTube, since being posted a little over a year ago, a reading Hughes did at UCLA shortly before his death had been played 12,226 times: amazing for an 85-minute, not-exactly-hi-fi, audio-only recording from 1967.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. As an African American icon Hughes is beloved, and as a writer Hughes has lodged his handful of poems permanently in the public mind. This has been true since 1921 when his first published poem, written when he was still a teenager, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” caused a sensation in black America. It remained true, as observed recently by W. Jason Miller, when Hughes’s poem from 1948, eventually known as “Dream Deferred,” was instrumental to the imagery and language of Martin Luther King’s 1967 “A Christmas Sermon on Peace.” And Hughes’s centrality was affirmed yet again in 2004 when presidential candidate John Kerry made use of the 1938 poem “Let America be America Again.” All of this is to note that, along with Whitman, Dickinson, and Frost, Hughes is arguably one of the few marquee names in American poetry.

Yet there remains a curious sense that Hughes’s poetry has never received the respect it deserves among the art’s cognoscenti. Certainly, race and racism are key factors in explaining why so few critics have championed Hughes’s poetry over the decades. His crucial role in the Harlem Renaissance, political activity, diversity of output, and, most of all, the hugeness of his position as a symbol of the African American writer has often overshadowed going too deeply into the specifics of any one aspect of his writing. Added to this, many of the powerful critics and scholars whose anthologies made academic reputations and who acted as gatekeepers to prestige with the majority culture showed little interest in the culture of black America that inspired and was explored in Hughes’s poems.

In addition, assessments of Hughes’s poetry have tended toward condescension, lip service, and more or less respectful silence. In 1959, James Baldwin articulated the basic knock on Langston Hughes’s poetry in a vicious takedown of Selected Poems for the New York Times Book Review:

“Every time I read Langston Hughes I am amazed all over again by his genuine gifts — and depressed that he has done so little with them.”

Few who have written on Hughes since can resist quoting this or some other part of Baldwin’s review. Indeed, even when not quoted directly, the echo of Baldwin’s complaint resounds through the years. Decades later, it can be heard via Harold Bloom’s introduction to a 2007 collection of essays on Hughes. “I come to the sad conclusion,” Bloom pronounces, “that Hughes’s principal work was his life, which is to say his literary career.” But in fact Bloom does mean Hughes’s life, going so far as to praise Arnold Rampersad’s biography of Hughes over its subject’s writings. Bloom’s conclusion: “Reading Rampersad’s Life is simply a more vivid and valuable aesthetic and human experience than reading the rather faded verse and prose of Hughes himself.” This is particularly egregious as Rampersad’s Life, as the biographer would be the first to admit, does not have access to key information about Hughes’s “human experience” that the poet was careful to conceal, including his sexual orientation and sexual activities (if any).

Bloom’s judgment also fails to explain or even to grasp why Hughes’s verse has not faded at all in the public imagination. The closest Bloom gets is a patronizing suggestion that it is not the quality of the poetry that keeps bringing readers to Hughes. “Social and political considerations, which doubtless will achieve some historical continuity, will provide something of an audience for Hughes’s poetry.” The awkwardness of this sentence is a perfect match for the distastefulness of Bloom’s assumptions.

Often, in the context of American poetry, Hughes is simply the Invisible Man: in view, yet unseen. This too begins during Hughes’s lifetime. One can scour the letters and essays of poet-critics like Randall Jarrell, Delmore Schwartz, or Robert Lowell (all obsessed with the work and lives of those they considered peers) in vain for any significant thoughts on Hughes. Of course, Hughes was passed over for recognition by the major poetry prizes. Even in small ways he was neglected. For example, despite being among the best-known writers in the nation, The Paris Review’s Writers at Work series, founded in 1953, which attempts to be definitive, never included Hughes despite having 14 years to interview him before the poet died.

Hughes’s appearances in the standard anthologies are similarly ambivalent. R. W. B. Lewis, writing an afterword to 50 years worth of correspondence between the two great classroom textbook creators Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks (Understanding Poetry), gently notes: “There is perhaps less talk in the letters than one would want about some aspects of the expansion process…” The expansion process being the inclusion in later editions of the anthology writers who were not just white men. Lewis admits among the topics not discussed enough was the decision to add a section on African American poets, including Hughes. Lewis is too generous. The published correspondence, 350 letters in which the two scholars otherwise describe in detail their creation and revision of five textbooks, doesn’t mention Hughes or the Harlem Renaissance at all. The letters give the sense that the inclusion of Hughes and other black poets was an afterthought placed in a segregated section of these textbooks: the real poetry lies elsewhere is the clear, if unintended, message.

Sometimes the racism was explicit, as in 1932 when, according to Rampersad’s biography, an associate of Brooks and Warren, the influential poet/critic Allen Tate refused to attend an integrated reception for Hughes at the home of a junior colleague at Vanderbilt in Nashville. Tate also used his considerable influence to make sure the event was cancelled because he thought it an insult to Southern tradition. Tate noted in a letter that he would certainly mix with Hughes up North but to do so in the South would be like socializing with his cook. No surprise that Tate’s Essays of Four Decades doesn’t mention Hughes’s poetry at all, even as it highlights Tate’s outsized role in bringing attention to Hart Crane, whose first book appeared the same year as Hughes’s debut. Hughes’s poetry never found such a champion.

Sandra Y. Govan well sums up the odd position Hughes holds within the context of his mostly white contemporaries: “Seldom is Langston Hughes included in the discussion of American modernists as either a poet or fiction writer,” she observes. “He may well be listed on an anthology’s table of contents, but typically he is grouped together with other African American writers as a member of the Harlem Renaissance … rarely is he discussed critically as a participant in the modernist movement.”

Yet a look at Rampersad’s biography reveals Hughes was a participant in his generation of poets far more than scholarship acknowledged. In Spain he reported on the civil war while palling about with Hemingway, and in Paris he met W. H. Auden and Stephen Spender. Closer to home, Hughes was connected enough to receive a note of encouragement from the madman at St. Elizabeths, Ezra Pound. He appeared on panels alongside the likes of R. P. Blackmur and exchanged ideas on poetry with John Crowe Ransom, a poet whom Hughes claimed to long admire. Among the last public appearances of his life, Hughes was asked to be a speaker alongside Robert Lowell to honor Marianne Moore at a Poetry Society of America banquet. “I consider her the most famous Negro woman poet in America,” was the ambiguous joke Hughes made that night referring to Moore. Rampersad sees the comment as more revealing than Hughes realized. “With a joke that was no joke at all in America,” Rampersad notes, “Langston sardonically revealed his contempt for the divisions that set even poets apart from one another.” And apart from other American poets is exactly where history has set Langston Hughes.

Rampersad offers an astute analysis as to why in the decades since his death Hughes has been so hard to integrate and evaluate alongside his modernist contemporaries:

To a substantial number of readers, and, especially, scholar-critics, Hughes’s approach to poetry was far too simple and unlearned. To them, his verse fails lamentably to satisfy their desire for a modernist literature attuned to the complexities of modern life.

And it is hard to argue this point. Where a good modernist should be comparing his angst to his ennui, all resulting from the hunger caused by the debased culture as culled from the ideas of Spengler and the imagery of The White Goddess, Hughes’s poetry presented characters more likely to face hard times because they were actually hungry for food.

So what sort of poet is Hughes? Hughes’s word for his technique was “simple.” Poetry, Hughes often claimed, should be “the epitome of simplicity.” And, since his death, Hughes’s simplicity has remained the focal point for most discussions of his work — both for those who praise the quality as well as for those who want to resist this as a strategy for understanding the poems.

Rampersad sees Hughes’s simple approach as a direct result of the poet’s desire to be understood by his chosen audience: the black America of his time. “One must accept the aesthetic that emerged from his desire to say little that his people, treated so shabbily by history and the master culture, could not understand and understanding accept,” Rampersad writes. “Fearing abstruseness and confabulation, because they were barriers between himself and his primary audience, he fashioned an aesthetic of simplicity born out of speech, music, and actual social condition of his people.” Indeed, Hughes’s verse uses common words, imagery drawn from the contemporary culture he shared with his audience, lines that often break with the phrase, lots of repetition, and subjects drawn from the everyday life, as well as the extraordinary events faced by black America of his time. But, as Rampersad surely knows, there is nothing simple about any of this: the music, speech, or social conditions of black America that Hughes used for his topics and materials. And there is much of Hughes’s poetry that is neither simple nor direct.

Like Frost’s sentence sound or William Carlos Williams’s conscious use of plain American speech, Hughes’s stated approach often has little to do with his actual practice. At his least memorable, Hughes is not so much simple but simply didactic, as in many of the communist-inspired poems of the 1930s. The controversial “Good-Bye Christ,” published in 1932 in The Negro Worker is typical:

Goodbye.

Christ Jesus Lord God Jehova,

Beat it on away from here now.

Make way for a new guy with no religion at all—

A real guy named

Marx Communist Lenin Peasant Stalin Worker ME—

I said, ME!

Yet even in what seems to contemporary readers a straightforward poem showing the poet’s excitement about communism replacing failed religion, at the time of its publication, “Good-bye Christ,” was deemed far more ambiguous. In “Langston Hughes versus the Black Preachers in The Pittsburgh Courier in the 1930s,” Walter C. Daniel traces how a series of conflicting readings of the poem enraptured newspaper readers after its first appearance.

Especially after this controversy, Hughes often hid in ambiguity when approaching subjects where his views could risk enraging black America. Or he offered poems that noticeably hinted at potentially controversial views while avoiding any statement as clear as “Good-bye Christ.” “Café: 3 A.M.” is a good example:

Detectives from the vice squad

with weary sadistic eyes

spotting fairies.

Degenerates,

some folks say.

But God, Nature,

or somebody

made them that way.

Police lady or Lesbian

over there?

Where?

Hughes’s sympathies may be clear, but they are also presented with a carefully cultivated plausible deniability. Had “Café: 3 A.M.” ended with the second stanza, it would have made a statement. But it is the two questions of the final stanza that move this poem away from the didactic and into the nervous paranoia of the unnamed observer who slyly underscores the earlier stanzas by being unable to “spot” any telltale difference between a “degenerate” and a “police lady.”

But no matter the subject, Hughes’s poetry often offered no easy resolutions, regardless of how simple a poem’s presentation. The two stanzas of the title poem of Shakespeare in Harlem (1942) are typical:

Hey ninny neigh!

And a hey nonny noe!

Where, oh, where

Did my sweet mama go?

Hey ninny neigh

With a tra-la-la-la!

They say your sweet mama

Went home to her ma.

Certainly the language of “Shakespeare in Harlem” has the simplicity of a rhyme used by children jumping rope. And one can see this as a call and response, with the child wondering where his/her mom has gone; the response being that the mother has left to go back to her mom’s home. But as strong a possibility is that the speaker in the first stanza is a man wondering where his “sweet mama” has gone and learning in the second that she has left him to return to her home.

But the questions only multiply from there. Big questions: Why is this situation Harlem’s version of a Shakespearean plot? And, small questions: Why does the fist line of stanza one end-stop with an exclamation point while the identical words again at the opening in stanza two are enjambed? These and other standard New Critical questions are raised in Hughes’s “simple” poems as surely as in the well-wrought urns authored by the other modernists.

Sometimes there is not even a pretense to simplicity. In the book-length poems Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951) and Ask Your Mama (1961), Hughes’s presentations are as complicated as other modernist long poems of the era. Both books begin with a note from the author, in the tradition of Paradise Lost, explaining their form to readers. For Montage of a Dream Deferred the instruction reads in part:

This poem on contemporary Harlem like be-bob, is marked by conflicting changes, sudden nuances, sharp and impudent interjections, broken rhythms, and passages sometimes in the manner of the jam session, sometimes the popular song, punctuated by the riffs, runs, breaks and disc-tortions of the music of a community in transition.

For Ask Your Mama, Hughes expects the reader to understand the musical notation used for “Hesitation Blues” and “Shave and a Haircut.” Certainly this compares in terms of formal demands from readers with Berryman’s The Dream Songs or Robert Lowell’s endless sonnets, if not exactly to more obscure and obtuse projects like The Bridge or The Cantos.

Of course, sometimes Hughes does seem as simple and direct as he is popularly imagined to be. Poems like “NAACP” and “Salute to Soviet Armies” are exactly what the titles lead you to expect. The first narrates the need for the organization to combat Jim Crow, which exists with total hypocrisy in the face of African American participation in a World War to fight for freedom against fascism. The second extravagantly praises the Soviet soldiers fighting against the Nazis. Poems that are consciously propaganda for the communists or against the Nazis or expressing rage at the treatment of black America bring out the most straightforward poetry in Hughes.

Often, this last category has a ripped-from-the-headlines quality that should remind us that, unlike any of his modernist poet peers, Hughes, even as a poet, was a full-time working writer. Many of these poems were written specifically to be sold and to circulate in the Negro press. Therefore, they unsurprisingly often reflected very specifically the stories and concerns of that newspaper readership. Poems like “The Mitchell Case” and “Governor Fires Dean” are typical examples that offer commentary on then-contemporary news: both share the identical opening line “I see by the papers” as the way they go about introducing their subjects.

All of this just scratches the incredible diversity of Hughes’s poetry. Like most working writers, Hughes made his money through volume. The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes includes over 860 poems in all. The need to sort through this massive amount of verse is where Hughes was particularly unlucky for the lack of attention from his poet-critic peers.

Consider Randall Jarrell’s famous 1953 defense of another awkwardly fitting modernist, Robert Frost. Frost’s aesthetic shares considerable ground with Hughes’s. Both Hughes and Frost liked regular spoken language, dramatic monologues, common folk as characters, and had a preference for stress and rhyme, if not always for traditional forms.

Jarrell in his essay claims there are two Robert Frosts:

Besides the Frost that everybody knows there is one whom no one even talks about. Everybody knows what the regular Frost is: the one living poet who has written good poems that ordinary readers like without any trouble and understand without any trouble…

Except for the loaded word “good” (italicized by Jarrell), Frost’s status as the “one living poet” ordinary readers can understand is clearly challenged by the example of Hughes. Of course, Jarrell was Nashville-born (Allan Tate published his first poems) and his sense of “ordinary reader” may not have included the huge audience of working-class black America that avidly embraced Hughes’s work and recognized their lives in his poems. Hughes’s poetry and audience both seem invisible to Jarrell.

Jarrell’s writing on Frost extracted the genial poet people thought they knew to reveal what he perceived as a darker Frost. Unsurprisingly, Jarrell discovered that, beneath the surface-Frost, this darker Frost turns out to be a complex, hard-to-grasp, and sufficiently miserable modernist after all. As obvious as this gambit may seem to us now, it is hard to underestimate just how influential Jarrell was in bringing legitimacy to Frost with connoisseur and academic audiences who had scorned Frost’s poetry as too popular and too simplistic before this. These are the same audiences which scorned Hughes and for similar reasons. But, throughout the 1950s, Hughes’s poetry never found a champion of Jarrell’s stature.

As a result, even today there remains little consensus on the legacy of Hughes. Writing an assessment of Hughes last year in The New Yorker, Hilton Als makes the unassailable point that Hughes is “uneven.” Certainly this is true. But what are the highs and lows in the arc of Hughes’s decades of poetry and hundreds of poems? To Als, the greatest of Hughes’s poetry is to be found at the end, in his final collection, the posthumously published The Panther and the Lash (1967). This featured many of Hughes’s political poems, the title referring to the Black Panthers. Whereas, to Rampersad, Hughes’s masterpiece occurred 40 years earlier with Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927), the collection where Hughes first made the breakthrough to blues-inflected forms. Meanwhile, both of the book-length poems have partisans. There is also the dramatic monologue sequence known as the “Madam Poems,” which has been singled out for praise by Dellita L. Marin, among others. In addition, we should not forget the anthology pieces for which Hughes remains best known.

In 1926, the year before the appearance of his formal breakthrough with Fine Clothes to the Jew, Hughes published a manifesto (another modernist poetry tradition) with his artistic statement of purpose in The Nation. “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” opens:

One of the most promising of the young Negro poets said to me once, “I want to be a poet — not a Negro poet,” meaning, I believe, “I want to write like a white poet”; meaning subconsciously, “I would like to be a white poet”; meaning behind that, “I would like to be white.” And I was sorry the young man said that, for no great poet has ever been afraid of being himself. And I doubted then that, with his desire to run away spiritually from his race, this boy would ever be a great poet. But this is the mountain standing in the way of any true Negro art in America — this urge within the race toward whiteness, the desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of American standardization, and to be as little Negro and as much American as possible.

It should be noted here that Hughes has no issues with the ambition to be a great poet for all readers. He simply argues against white aesthetics being universal, urging instead an embrace of the forms that he believes are the unique inheritance of the Negro artist. Hughes’s argument is not with the majority culture, but with conservative critics and middle-class readers demanding young black artists paint sunsets and write sonnets while despising expressions like jazz and blues. Near the end of the essay, Hughes gives an honor-roll call of the art he admires and whose example he follows:

Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing the Blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near intellectuals until they listen and perhaps understand. Let Paul Robeson singing “Water Boy,” and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem, and Jean Toomer holding the heart of Georgia in his hands, and Aaron Douglas’s drawing strange black fantasies cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.

Hughes rejected an establishment that wanted poets like him to be “race men” who must always be careful to present black life in a positive way to the outside world. To the chagrin of these critics, Hughes’s poems often had characters who were drunk, lazy, promiscuous, and violent. In many ways, this was the identical fight Philip Roth waged a generation later against Jewish establishment critics infuriated by the way his stories presented: for example, Jewish families squabbling over money.

Hughes concludes “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”:

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

Hughes followed his muse; at the time the result was a poetic language based on music, slang, and a culture that other modernist poets and critics of Hughes’s day knew nothing about. They thus lacked the tools to get beyond the simple surface of his poetry.

But it has been 90 years since Hughes published “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” and time has borne out his hopes for “tomorrow.” The urban working-class lives depicted in Hughes’s poems are likely far more familiar to contemporary readers of all races than the rural lives depicted by Robert Frost, which now seem like they are from another era. Meanwhile, the blues and jazz music that inspired Hughes’s forms is far more generally recognizable than the iambic pentameter that Frost’s poems mostly maintained despite sentence sound. Indeed, Hughes’s concerns — from racism to police brutality to income inequality — can all easily be seen as making Hughes uniquely suited to our times. If so, we may finally begin to truly map, climb, and grow to know the mountain of poetry that is the great artistic legacy of Langston Hughes. •

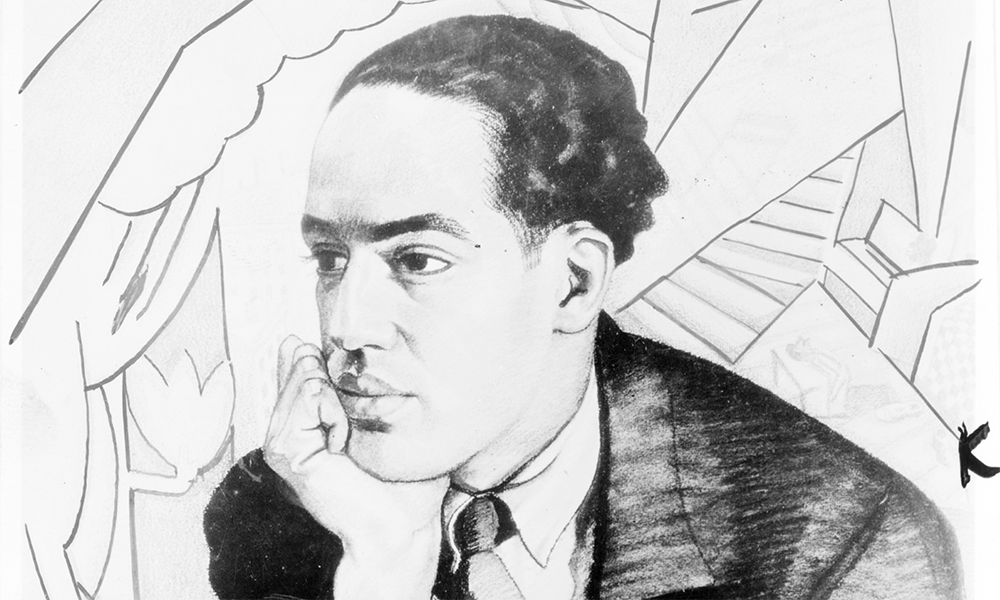

Illustrations from 2 portraits of Langston Hughes by Winold Reiss, courtesy of the Library of Congress (via Wikimedia Commons) and the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.