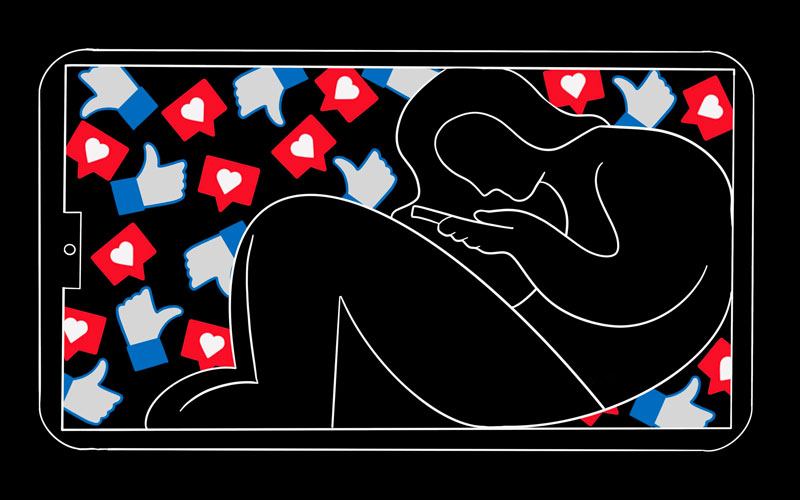

Humans are social animals, and our brains are wired accordingly. When a brain is socially isolated, it will crave social interaction in the same way that a hungry person’s brain will crave food. And yet, we live life in defiance of these facts. While our brains want to be fed social-connection broccoli, we feed them Skittles piece after piece after piece instead. As a result, society limps along with skyrocketing rates of depression, anxiety, and loneliness. Meanwhile, we avert our eyes and accept these relational deficits as the norm.

A conservative 35,000 years ago, our brains reached their current state of development by evolving to meet the needs of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Anthropologists estimate these early humans had contact with fewer than 100 other humans over the course of their entire life. Without getting off my couch, I can contact more people than my early ancestors could fathom existing — a quantity far exceeding what my brain evolved to handle. Connections? We have them in spades. We have depression, anxiety, and loneliness in spades, too.

Every warning light on our modern societal dashboard is flashing. It’s obvious that we have a problem. And we excel at pointing out the problem. Repeatedly. Study after study confirms it. But instead of course correcting, we chug along, hoping to make it to our destination before our society collapses or explodes.

•

Numerous findings show a positive correlation between countries with individualistic values and the prevalence of loneliness. The more individualistic a country is the lonelier it is likely to also be. Unsurprisingly, the United States ranks highly in both categories. In 2018, Great Britain, a similarly individualistic and lonely nation, identified loneliness as a major public health crisis and responded by creating a new ministerial position, Ministerial Lead for Loneliness. Among American Millennials (my generation), 27 percent say they do not have a single close friend. And 22 percent say they have no friends at all. None. These studies were conducted pre-pandemic and do not account for the further, pandemic-driven attrition of friendships reported by nearly half of Americans. Regardless, the findings mark staggering declines and help explain why nearly a third of Millennials say they feel lonely often or always (compared to only 15 percent of Baby Boomers). Statistics like these are so commonly uttered that we have grown numb to their impact. But behind the stats are real people. Maybe someone in my neighborhood. Or the familiar face ahead of me in line at the grocery store.

As Great Britain noted, loneliness impacts both mental and physical health. The CDC links loneliness and social isolation to numerous adverse physical health outcomes including increased risks for dementia, heart disease, stroke, heart failure, premature death, and suicide. Because we are social creatures, the quality of these relationships matters too. The CDC states that “high-quality social relationships” help us “live longer, healthier lives.” But how many of our social interactions are even aiming for quality?

Previous generations formed connections and community reliably in places of worship. But for the few Millennials and Gen-Z who do attend church, church is an experience rather than a community — an experience that echoes the personal tastes and preferences of its customers, not a locus for meaningful connection.

Technology allows many of us, me included, to work from home. We shoot off emails or better yet, texts in lieu of phone calls. We only meet face-to-face when absolutely necessary. A meeting. A coffee. A quick lunch. We spend our free time checking-in with friends, many of whom we have not seen in years, via likes on social media. Our days are filled with nothing more than surface-level interaction tick marks.

Our culture celebrates self-reliance, individuality, and independence. And we equate these with autonomy and freedom. Oh, how Americans love their personal freedom. Yet, despite unprecedented access to others, we feel increasingly disconnected.

We normalize the frequency of relational breaks: so-and-so moved, life got busy, kids, new job, etc. But most of the time, it’s our mindset, not logistics, that creates the biggest barrier. Investing in the lives of other humans and them doing likewise for us not only requires time and energy; it also requires risk. Even and possibly, especially, our closest relationships will all eventually have disagreements and conflicts. Save for the 22 percent of Millennials without friends, relationship conflict is inevitable. The problem is that other aspects of our lives have become so controllable and curated that we respond to relational turmoil like an F-22 pilot with an ejection button and a parachute. Almost reflexively, we make an exit.

•

Until weeks before he passed, my great-grandfather had breakfast with the same group of grumpy old men every Friday. For decades. They called themselves The Coffee Club, or maybe that’s what the rest of my family dubbed them. Either way, through disagreements, misunderstandings, and differences in politics and religion, The Coffee Club met at the same diner every week. If my great-grandfather didn’t like what someone was saying, he turned down the volume on his hearing aid (his era’s version of silencing a Twitter feed). But no matter who disagreed with who the week prior, my great-grandfather showed up the following week and ordered his two eggs over-medium with bacon and hashbrowns. They all did.

But instead of taking a page from The Coffee Club, our society places a higher value on personal autonomy than relational longevity. We don’t need to depend on others; so, we don’t. And based on the data, this approach has detrimental effects. But whether due to our individualism, narcissism, or propensity for conflict avoidance, the effect is the same: a systemic devaluing of relationships.

Rarely do our relationships weather a major disagreement and come out on the other side intact. Forgiveness is an even rarer bird (an area where I am admittedly a work in progress). But this relational devaluing permeates more deeply than we might realize. Our experience of the world has become so self-referential that almost everything we see mirrors our values, likes, and interests. For this, we can thank technology. Even as you read this, your device is learning and curating what to show you next, further reinforcing your worldview. Tricking you and me into the belief that our opinions and perspectives are far more universal than they are in reality — further fanning the flames of endemic self-importance and narcissism.

Yet, no matter how good the algorithms on our devices get, one variable they will never be able to control are other people. As a result, we opt for our F-22 ejection seats when conflicts arise rather than digging deep. We trust the convenience and availability of low-stakes, tick-mark interactions to fill in any connection voids. Skittles not broccoli. In the process, have we forgotten how to build the kind of relationships that require decades of showing up at the same diner every Friday morning? Connections that require personal investment, forgiveness, and commitment. Even when disagreements occur.

This question comes with a caveat, however. For something to be forgotten, it must first have been learned. And based on the collective mental health of Millennials and younger, I think we are wearing out our ejection seats. As a result, most relationships are too fragile to sustain injury. We made all our houses out of sand without learning to build anything else.

•

Two years ago, I started walking with a group of women. We meet at 6 a.m. every morning and walk the same neighborhood loop with a coffee shop stop halfway. I’m the youngest regular by at least a dozen years and the only Millennial. Some of the women have been friends for nearly as long as I’ve been alive. How I, an Olympic-level introvert, landed in the group is a bit fuzzy, but after repeatedly crossing paths, I agreed to join for them what was supposed to be just one morning. Somehow that one morning turned into two years and counting.

The Walking Group, as we refer to ourselves, exemplifies the rare and dying breed of community that is only forged by many years of mutual investment. The group’s support of one another bleeds far outside the confines of morning walks and defies American tendencies toward self-reliance and isolation. And I can confirm, firsthand, this brand of community can change your life. Not just because someone will bring over soup when I get sick, although they will. But because it’s the kind of deep-rooted, relational connection-broccoli that my brain is wired to need — and I hadn’t realized was missing. Figuratively and literally, this group has walked with one another through life-altering challenges and losses. One person’s heartbreak is everyone’s heartbreak. It is the antithesis of American individualism. They know how to show up for 6 a.m. walks, each other, and life.

But occasionally, there are disagreements. Privacy is invaded. Boundaries are overstepped. Discussions on politics and religion get heated. On these topics, some of our Venn diagram-overlap very little, if at all — proof that you can love someone and disagree with them. Yet, conflicts that would be contentious enough to estrange families have been resolved through grit and resilience. Their relationships are not made of sand.

•

The Walking Group wasn’t my first introduction to a community in action. I grew up in the small fishing villages of Southeast Alaska. Remote locations force your hand on the community front, making the members collectivists by necessity. Interdependence is woven into the village’s DNA. Places where everyone knows everyone — yes, literally. No one is ever too busy to help; in fact, they go out of their way to do so. Next time, the helper might be the one needing assistance, and when populations are measured by the dozen, you can’t afford to make enemies. One person’s kid is everyone’s kid, which, as a former “everyone’s kid,” comes with pros and cons. It granted my brother and me a level of freedom that we never would have had in the city. But when we zipped down a trail way too fast on our four-wheelers, we were scolded by the whole village, not just our parents.

I have fond memories of growing up in these small, tightly-knit communities. But in my mind, this type of community had a box that belongs only in small-town Alaska. In locations where your community can mean the difference between life and death, it is integral. But what could save my life in one place is a box I can choose not to open in another. At home in Seattle, I can retreat to self-reliance without loss of life. If needed, I’ll just Google my way to a professional.

Although mostly Seattle-based, my husband and I have a cabin in the Alaskan interior. While the town is more populous than the coastal villages of my youth, its relational environment felt familiar to child-me and moderately suffocating to the adult-me, who highly values privacy. My feelings aside, the extent to which Alaskan residents go out of their way for one another, offer help and check in on each other is truly something to behold. In the best way possible, they are downright un-American.

One winter, my husband and I were en route to our cabin. That day was -20 degrees Fahrenheit. A friend, who knows how much I hate being cold, didn’t want us to walk into an icebox in the middle of the night. So, he drove out to our cabin, shoveled a path through six-foot-deep snow to the front door, and fired up the woodstove a few hours before we arrived. When we pulled in late that night, the fire was still going, and the cabin was already toasty warm inside. I sluffed off my snow clothes and sank to my knees in front of the glowing stove. As my face and fingers thawed, I don’t know if I’d ever been more grateful for a strong community than I had been that night.

This same caring community also shows up without an invitation. Constantly. The meal I had been making for three now must be doubled to feed everyone, which is more challenging than it sounds in a cabin with no running water. I’ve had tag-a-longs on four-hour car rides because “Hey, I’m headed to the same area! I’ll ride with you.” — an intrusion also known as introvert hell. But I’ve learned community is intrusive by nature. It pushes my comfort zone and forces me to check my introversion at the door. And sometimes, I want to hide from it.

But these same people, who drive me absolutely batty, spend hours figuring out why our cabin’s solar panels aren’t working properly. They jump to my defense like older brothers when drunk tourists make lude passes at me. And before we even knew it was damaged, they repaired our chimney. I could go on. So, while this chosen family of mine can be absolutely crazymaking, I also love them dearly. Both are true. Ultimately, the reason they can eat my food, borrow stuff without asking, invade my space, and hug me even though I’m not a hugger is that we are permanent fixtures in each other’s lives. They are more my family than my actual extended family. And despite what the western societal narrative says, there is a freedom that accompanies this kind of permanence.

From my front window in Seattle, I can count more than a dozen houses. At the cabin, that number is zero. Despite its geographic isolation, for many years, that was where I felt the least isolated. I love the impact my cabin community has had on my life — the comfort, support, and love of family. And I selfishly also loved that it stayed in its box. In Alaska. At the cabin. The idea of such a substantive community invading my Seattle life made me sweat. Even with the luxury of running water, I appreciate having a finite headcount for dinner most nights. But since Seattle is a city famous for socially freezing people out (hence “The Seattle Freeze”), I wasn’t worried. There, community is a concept that barely exists and rarely functions well. It’s optional. If it’s convenient. But never a necessity. The warning lights on the dashboard of the city are flashing, but everyone swallows the lie and chugs along.

•

In their Brooks sneakers and yoga pants, The Walking Group women do not look like radicals. But they are a 6 a.m. resistance movement. Their cause is imperceptible to anyone outside its orbit. But that’s the power of a strong community; it stealthily extends beyond itself, blurring its own borders. Together, these women have birthed foundations, city outreach organizations, successful fundraisers, and thriving non-profits. On a more personal level, our own households are better off too; everyone’s kids have a gaggle of honorary aunties cheering them on.

For many cultures, reliance on community is a trademark of a healthy society. But American culture throws out humanity’s hard-wired appetite for connection in favor of the story that relational-atrophy and hyper-individualism are normal — as if our society has somehow evolved beyond a state of interpersonal dependency. Leave it to a nation founded on independence and freedom to take those values so far that they betray human biological wiring.

I’ve learned innumerable lessons from The Walking Group. They have shown that community is just as important in the city as it is in a remote fishing village, thus dismantling my box theory. But the biggest thing I have learned is also perhaps the simplest. Show up. Communities like theirs are only possible when people prioritize one another. And their bonds did not form overnight; they required fortitude and time. Two concepts that are incompatible with my instant gratification generation, who survive on a steady drip-drip-drip of low-stakes, low-investment interactions that satiate connection-appetites just enough to keep them in check. My generation believed the lie that self-sufficiency and independence lead to greater freedom. And that freedom equals progress.

No matter what we tell ourselves, our society is growing increasingly narcissistic, lonely, and disconnected. We have taken independence to the breaking point, and the collateral damage is the mental, physical, and emotional health of the Millennial generation and younger. It’s time to pay attention to the flashing lights on the dashboard. We need to learn the lost art of showing up.•