“Tonight is Prufrock,” I say. My friend and colleague, Em*, and I are sitting over cooling coffees in the Student Center.

Her nose scrunches in a way that says that maybe this isn’t such a good idea, “Are you sure you want to start with that one?” she says, “Prufrock is a tough poem. I’ve had some real disasters with Prufrock.”

My coffee is sludge, but I gulp it down anyway, “I’m going in,” I say, “Any last words of advice?” Em is a poet and a scholar of Modernist poetry and thus my go-to person for poetry pedagogy.

She leans forward over the table, all seriousness now, “Guide them through a close reading of the first couple of stanzas yourself before having them take a crack at interpretation. The first stanza seems to be where they get into the most trouble.”

I glance at the clock over the café. I have exactly two minutes to get to class. I sling my messenger bag over my shoulder and toss my empty cup into the garbage, “Thanks,” I say, but inside I’m all swagger. She’s exaggerating, I tell myself.

In class, we sit in a semicircle with our books open in front of us. I read the first few lines aloud:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table

There’s some fumbling with phones as students look up the word “etherized” and then some discussion as to what that image might mean. After they’re unable to come up with an answer, I suggest we move on:

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells

And here is where the discussion starts to go off the rails.

“He’s with a prostitute,” says Whit. He’s one of my older students, mid-to-late 20s, works full-time during the day, comes to class with his briefcase and the top button of his button-down shirt undone.

“Oh?” I say.

“We read this poem in our other lit class. Our professor said the person he’s with is a prostitute,” says Whit.

“Oh, yeah!” says Joey, another student, “The ‘cheap hotel’!” I see it now!”

“Wait . . . Let’s — ” I say.

Back to Whit: “He’s walking in the red-light district with a hooker.”

“What’s a red-light district?” asks Joey. He’s a second semester freshman, all of 19-years-old.

“Wait!” I say, holding up one hand. They turn from Whit back to me, “Could it be that your other professor said that is one interpretation of the poem? An interpretation?”

Whit looks down at his open book as if he’s considering my suggestion. He shakes his head, “No,” he says, “he said the other character in the poem is a prostitute. I’m sure of it.”

In the meantime, the three young women in the class are bent over their books.

“I don’t see it,” I hear one of them say, but before I can bring her into the conversation, Joey jumps back in: “Here in this stanza,” he reads aloud: “‘Arms that are braceleted and white and bare.’ See? She’s naked!”

“They are in a steam room.” This from Luis. English is his second language and he’s struggled all semester to keep up with the readings.

Maybe it’s a matter of translation, “A steam room? Where do you see that?”

“The yellow fog in the third stanza,” he says, “That is an image for a sauna. They are at a spa.”

Joey nods, “Brothels have steam rooms, right? Where everyone sits around naked?”

One of the young women, Amina, rolls her eyes. The men ignore her. They’re leaning together over the yellow fog stanza. I feel what little control I imagined I had over the discussion drifting away like . . . well . . . like yellow fog.

“I can promise you they’re not in a sauna, Luis,” I say, but no one seems to hear me, “What about the ‘taking of a toast and tea’”? I ask, trying to direct them to other parts of the poem. Amina raises her hand, but before I can call on her, Joey’s brandishing his Norton reader and pointing, “Here,” he says, “‘And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin, / When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall…’ Pin! Isn’t that an image for sex? Like intercourse? The prostitute is being ‘pinned’?”

“Ugh,” says Amina, “he is the one being pinned. There’s no mention of a woman.” Her cohorts, Team Not-Prostitute, nod.

Before Team Prostitute can respond, I hold up my hand, “I just want you to take your time and go through the poem before arriving at a conclusion. Now that you’ve found evidence to support this one interpretation, let’s consider other options.”

Whit stands up so suddenly that his desk slams into Joey’s. He strides out of the room, slamming the door behind him. The class falls silent, eyes fixed on the door.

I direct them to a writing activity. We’ll revisit Prufrock next class, I promise. After I’ve had time to recover, I think, but don’t say.

During the drive home, I think about how on the one hand, I’m proud of my students. They twisted and wrung their interpretation out of poor Prufrock. In the words of Billy Collins, they

tie[d] the poem to a chair with rope

and torture[d] a confession out of it.

They beg[a]n beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

But on the other, I’m dismayed at how they were so willing to follow someone else’s interpretation of the text: Whit, his (interpretation of) his other professor’s interpretation, and many of the other (male) students following Whit. When certain lines of the poem (“taking of a toast and tea”) didn’t fit their view, they simply disregarded them, or didn’t even acknowledge their presence.

Why do students struggle so much with “reading against the grain”? Why do they willingly follow the opinion of the majority? Well, for one, it’s easier; concordance requires less thinking than resistance. For another, it’s safer. After all, who wants to be an outlier against an authority figure, such as a professor? But beyond those reasons, or beyond mere intellectual laziness, the predominant interpretation holds sway because students have been trained that their emotional response to a text is just as valid as, say, what it means to read a text within its historical or cultural context. They’ve also been taught to seek out that one “correct” answer and to fill in a corresponding bubble on a Scantron. Context has been swept aside by students who have been instructed to find THE answer through “context clues” and by reading the lines above and below the section they’re attempting to understand. That’s how you end up with “woman” and “bare” equaling a prostitute even if she’s partaking in “toast and tea” several lines down or in a whole other stanza. In an age where absolutist truths are mediated through clickbait headlines and memes featuring the Dos Equis man, perhaps the value of a discussion where a student storms out of the room in frustration, is that discussion is possible. It’s necessary. It’s important. It says that reading is a political act. One might even say that the task of those fortunate enough to spend an evening discussing Modernist poets with a group of young people barely out of high school, is not to assert but to question, not to push but to pull, not to read with, but against. Yes, I had been happy to see an engaged class, an energized discussion, but wished they had been more open to considering other options. Isn’t it easier to lock that target on “the answer” than to dig a little deeper? For all of us? I’m talking here beyond poetry, beyond literature, to issues that plague society, of intolerance and exploitation, of brutality. One could argue that the study of “liberal arts” encourages the development of critical thinking. One would hope that being able to apply this skill to “Prufrock” might result in a populace that could apply it to, for example, the issue of excessive force by those in a position of power.

I call Em and tell her the story. To her credit, she doesn’t say she told me so, although she does sigh, “It’s a tough poem,” she says again.

•

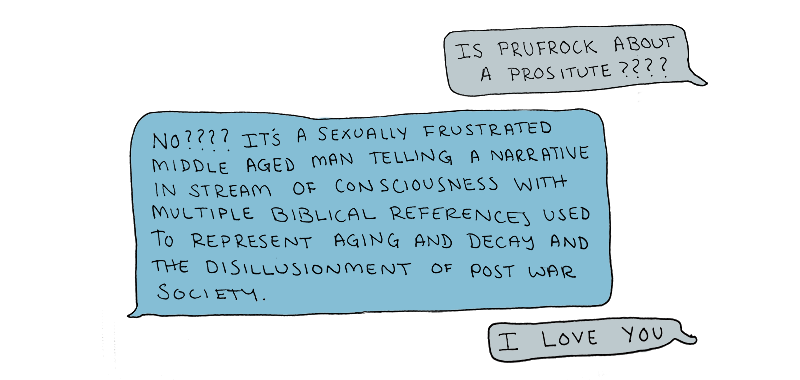

When I get home, I text my daughter who is away at college. She’s a huge T.S. Eliot fan. In fact, I gave her a collection of his poems on the day of her high school graduation. Here’s what she said:

Yes! I think. Didn’t my students remember my lecture on Modernism? Apparently not.

The next morning, I’m in the copyroom when I see Professor Dickinson. I know he’s teaching American Literature this semester. “Excuse me, Sam,” I say, “did you recently discuss ‘Prufrock’ in your class?”

He slaps his hand on a stack of papers on the copy machine, “Yes! Do you have Whit in your class?”

“Yes!” I cry, “Did you tell them that there’s a prostitute in the poem?”

“No! I told them that was one possible interpretation. One! But Whit was quite taken with it. In fact, I had a hard time moving the discussion beyond that point,” He picks up the stack of papers and puts it in his bag, “Although . . . ” He stops.

“Although?”

He settles the strap of the bag on his shoulder and clears his throat, “There are references in the poem that point to that interpretation,” he says, “Did you know the mermaid was a symbol for prostitution in the nineteenth century and was often displayed above the door to indicate the presence of a brothel?” He must see something in my face because he rushes on: “I never meant for them to take my interpretation as gospel. I explained to them that Modernist poetry is ambiguous. But once the prostitute was out of the bag, so to speak, I couldn’t put her back in,” he chuckles.

“Well,” I say.

“In retrospect, maybe I should have let them have a go at the poem first before sharing that bit of information with them.”

“Maybe,” I say.

When next we meet, I instruct the class to take out their books and open to “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” I then take them through the poem, line by line, metaphor by simile, image by image. I talk for about half an hour. They’re all scribbling madly. Once in a while, I ask a question, but for the most part, I talk and they listen. I share with them my conversations with Em, my daughter, and Professor Dickinson.

“You won’t find only one right answer,” I tell them, “Understanding comes through reading and then rereading, discussion, and writing. Every time I read a poem like Prufrock I make a new discovery.” Some of them look blankly at me, but Amina is nodding. So is Joey.

I wish that Virginia Woolf could weigh in here. She, who called for the killing of angels, would protest that Eliot’s women are trapped in that room, not their own, where they are forced to “come and go” with their bare braceleted arms, while they wait to assuage the loneliness of men, despite the starkness of their own perfumed objectification. Is it any wonder that several of my male students leapt to an interpretation that commodified the female presence in the text?

I want them to do all the things: read against the grain, interrogate their own assumptions, and the biggie: think critically about what they read. In the end, however, Eliot’s “sea-girls” must speak for themselves even if it means they’re whispering one thing into the ears of my male students while beckoning the women to follow them out of the fog and into the “chambers of the sea.”

As Prufrock himself might ask, “Do I dare / Disturb the universe?” Do I dare teach “Prufrock” again? I think that I will. And what if these students never read Eliot again after this class? I hope, though, they they take something away from this experience even if it’s that just because there’s a woman in a poem, it doesn’t mean that she’s a prostitute.

*Names have been changed. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.