How many artists out there can say they completely transformed an entire genre so much that there is a clear demarcation point between what came before and what came after?

Manga artist Moto Hagio can. She had help, though. As one of the members of Magnificent 49ers, also known as the Year 24 Group, Hagio is a member of a loose affiliation of female cartoonists all allegedly born in or around the 24th year of the Showa era (1949, hence the name), that transformed girls’ comics in Japan, a.k.a. Shoujo manga.

Before the 49ers, according to translator and manga scholar Matt Thorn, shoujo was “a backwater” dominated mostly by men who churned out forgettable, formulaic romance stories where the female protagonists played a largely passive role (a notable exception being Osamu Tezuka’s Princess Knight).

But then in the mid-1960s, a boom in manga readers, along with a shift in perception of gender roles in Japan, led to more women coming to the industry. And, in the case of the 49ers (who came to the scene roughly between 1969 and ’71), the comics they started making pushed boundaries, both aesthetically and in terms of subject matter.

The 49ers expanded their storytelling scope far beyond the simplistic romance formulas of the day to focus instead on more expansive genres like science fiction, historical fiction, and horror. There, they explored societal and sexual issues (oppression, abuse, gender roles, homosexuality) that many boys’ manga (a.k.a. shonen) didn’t dare touch.

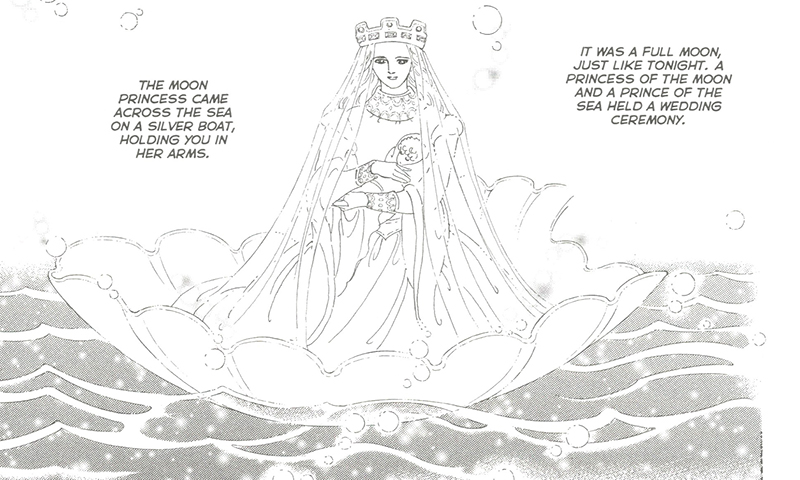

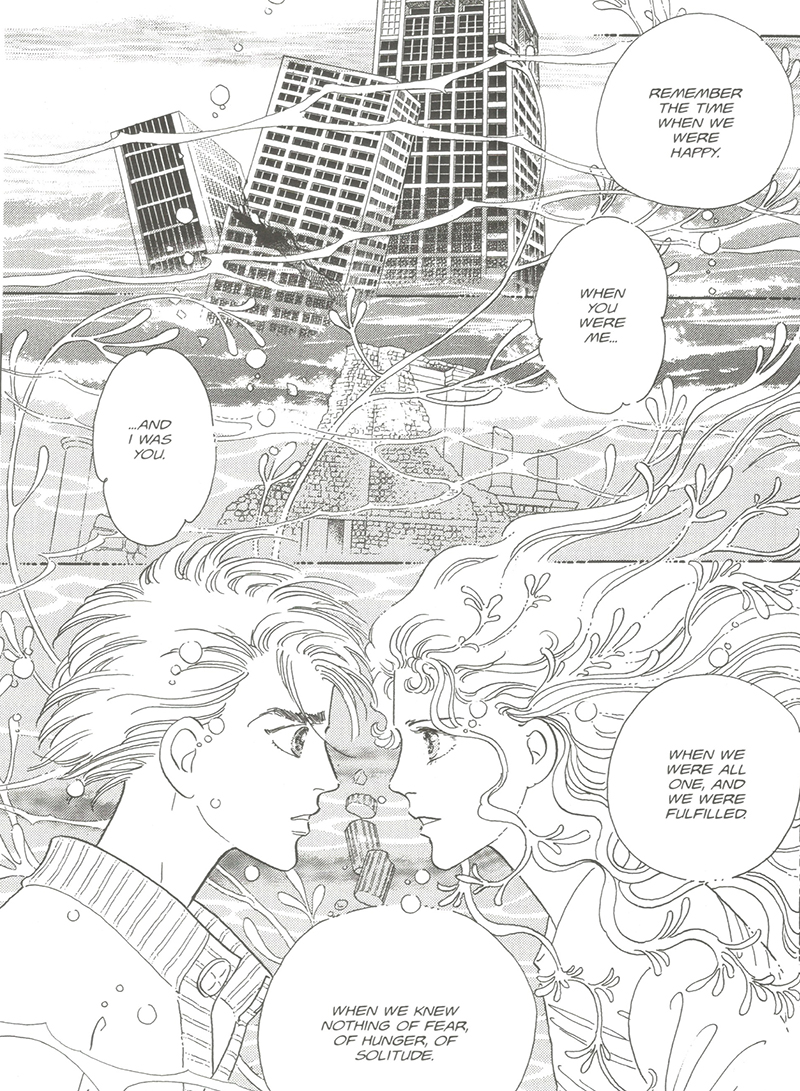

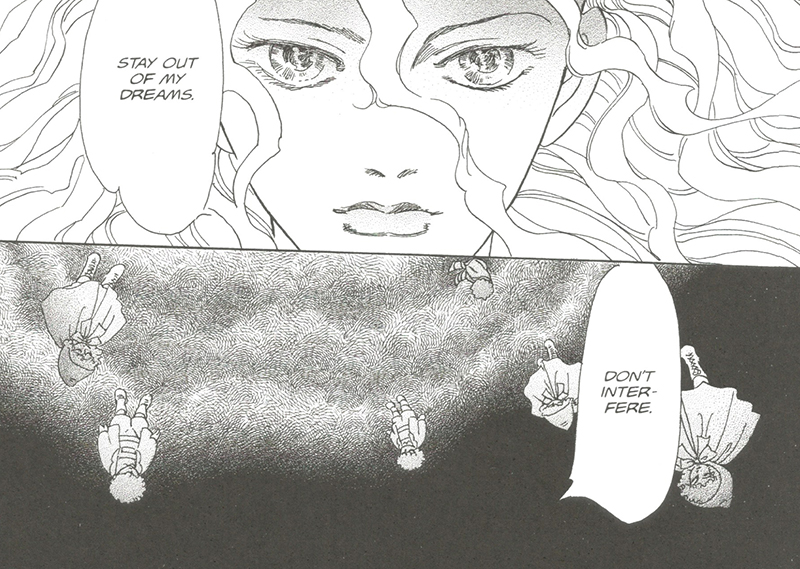

And whereas shonen manga focused almost exclusively on external action — all speed lines and frenetic movement — shoujo was all about the interior world, with characters’ pained expressions breaking through panels and their daydreams and longings filling up the page, all drenched in dappled sunlight. Indeed, many of traits that westerners normally associate with “manga” — androgynous male leads, large, dewy eyes — find their origins in shoujo manga. (I hope don’t have to drive the point home, however, that this sort of trite, blanket stereotyping of manga shortchanges the medium and people working in it considerably. Manga is as rich and diverse in artistic styles and tropes as any commercial art form.)

There’s considerable debate about who does and doesn’t belong in the Year 24 Group (other members include Keiko Takemiya, Yumiko Oshima, Ryoko Ikeda, and Ryoko Yamagishi) and many of the cartoonists affiliated with it dismiss the existence of the group, saying it’s just an invention of critics, but one thing is clear: Real or invented, Hagio was one of the leaders of the pack.

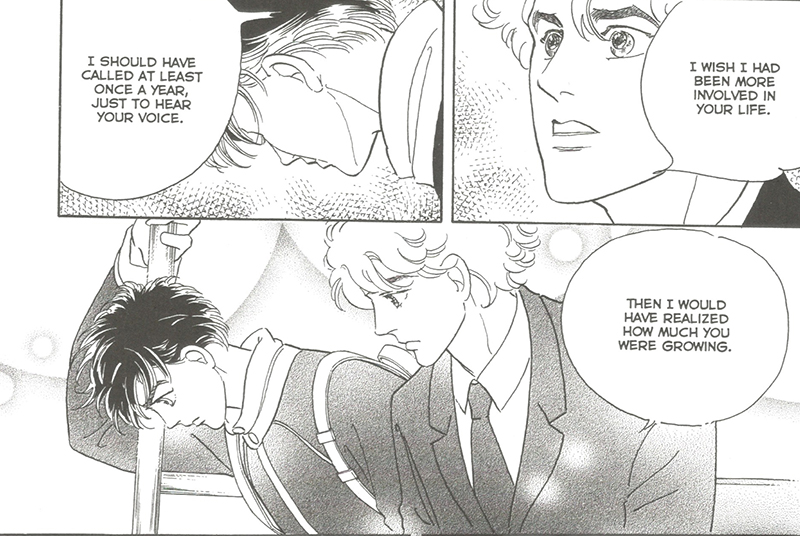

Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, Hagio made her name with works like Heart of Thomas (a seminal work in the then-nascent shounen-ai genre — i.e. chaste, homosexual love stories for straight girls), They Were 11, Marginal, Mesh, and A,A’. Her stories focus on eccentrics or outcasts, people pushed down by societal or familial forces who tried to find a place for themselves. Within the realm of melodrama and fantastic sci-fi settings, she has deftly handled such fraught topics as childhood trauma, dysfunctional families, sexual abuse, absent or aloof parents, nature vs nurture (especially as it pertains to genetics), homosexuality, gender politics, and identity.

While much of her work remains untranslated into English thus far, the alt-comics publisher Fantagraphics has published a number of Hagio’s works in recent years and now they’ve released the first volume in one of her more recent works, Otherworld Barbara, originally serialized between 2002 and 2005 (volume two will be available in 2017).

Set in the near future, Otherworld Barbara concerns itself with a young woman (not named Barbara) who has been in a coma for nearly a decade after allegedly having killed her parents and quite literally consumed their hearts. A psychic/therapist, Tokio Watarai, with the ability to enter dreams, is hired by the woman’s extended family to try to awaken her. What he finds inside her subconscious, though, is an elaborate island world, inhabited by fully realized people who claim to be living in the year 2150. Is this woman somehow dreaming of the future? Or is something even stranger going on?

More complications ensue. Tokio has an estranged son, Kiriya, who claims to have created this mysterious island world (which — surprise — is the titular Barbara). What connection does he have with this comatose woman? What role does the mysterious minister Sera Johannes play in it? And what of the young man who insists that Kiriya is a long-lost childhood friend? And what does any of this have to do with the planet Mars?

As my summation suggests, it’s a pretty dense story, with a lot of balls that have to be kept in play and revelations to be teased, but Hagio does a suburb job of keeping the reader in suspense without losing them down any narrative rabbit holes. Otherworld Barbara is never convoluted or confusing despite its elaborate plot.

Barbara is dense with ideas as well. Influenced by Noam Chomsky, Ray Bradbury, Carl Jung, genetics, neuroscience, and more (there’s even a joke reference to Last Year at Marienbad), Hagio explores identity, aging, and our flawed perception of reality. But the high-minded philosophical explorations are grounded by the fraught emotional landscape of the characters. As mentioned before, broken or dysfunctional families are familiar territory for Hagio (she has spoken publicly about her own issues with her parents), as are characters who are so emotionally reserved they could fall somewhere on the autistic spectrum. Here, though, the anger over neglect from parental figures (and adult authority in general) constantly threatens to spill over into violence — it is frequently suggested that the withdrawn Kiriya could do Tokio real harm — as though despite the relative lack of blood on the page everything is building inexorably toward a tragic climax.

Amidst the angst and philosophizing, Hagio delivers some truly striking images. Giant raindrops shaped like children that splash on the pavement. An androgynous man who lives in a birdcage. A village that consumes the organs of the recently deceased in order to gain immortality. All of it depicted with Hagio’s expressive razor-thin line. Whether depicting wooden sword fights in the streets, interior dreamscapes or simple conversations, her art is never anything less than fully assured. Fully detailed yet never seeming cluttered or overly busy, she is a master in being able to convey raw emotion and subtle facial expressions.

So very little “classic manga” has been made available to Western readers that can be difficult for ardent fans to fully grasp how Moto Hagio and the rest of the Year 24 Group laid the groundwork for a good deal of the manga and anime they enjoy today. It’s encouraging then to see a company like Fantagraphics making the effort to get Hagio’s work out in North America. Even more encouraging, however, is to see that with Otherworld Barbara, Hagio has not lost a single step and remains a compelling, captivating storyteller. •

Images courtesy of the author and Fantagraphics Publishing