If you were to ask an expert (and that would most decidedly be not me) who were the true greats in the world of manga — your Charles Schulzes or your Jack Kirbys, for example — those whose influence spread far and wide across the medium — two names that would likely roll off the tongue would be Osamu Tezuka and Yoshiharu Tsuge.

The pair are in many ways a study in contrasts. Tezuka — the creator of Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, among many, many others — was incredibly prolific, worked in multiple genres, and usually tailored his comics towards a mass audience. Tsuge, on the other hand, has a much smaller bibliography, made comics for a limited audience, and devoted himself to a mode of comics that encouraged artistic self-expression in a manner previously not seen in manga.

Another contrast is that while many (though far from all) of Tezuka’s works have been published in North America, very few of Tsuge’s works have seen the light of day here. Only two short stories published in the seminal ’80s anthology Raw and his iconic “Screw-Style” comic, published in the 250th issue of The Comics Journal, have seen print on these shores (assuming you don’t count the scanlations). For those who have heard or glimpsed Tsuge’s work and want to see more of his work, it’s been a frustrating experience.

Now that has suddenly changed. This year has seen the release of not one but two books — The Man Without Talent, published by New York Review Comics, and The Swamp, published by Drawn and Quarterly, and the first volume in what is promised to be a complete run of the artist’s work. These two books, ostensibly representing the start and end of Tsuge’s cartooning career, serve as bookends for incoming readers, allowing us to see the young cartoonist find his footing as well as discover a master fully in command of his abilities.

The Swamp begins with some of Tsuge’s earliest work, though it ignores the nascent material he did for the rental market (where customers could rent instead of buy collections of manga). Bearing the subtitle of “the mature works” The Swamp instead starts with the initial comics he did for Garo magazine — a seminal monthly anthology that specialized in artistic, expressive manga — between 1965 and ’66.

The Swamp can be divided into three sections. The first is a collection of stories about dissolute and poverty-stricken samurai. Here these figures are viewed less as heroic or noble warriors than as bureaucrats and functionaries adrift In a world that doesn’t seem to require their services (and if you draw any parallels between that and the life of an aspiring cartoonist, well, I’m sure that’s just coincidence).

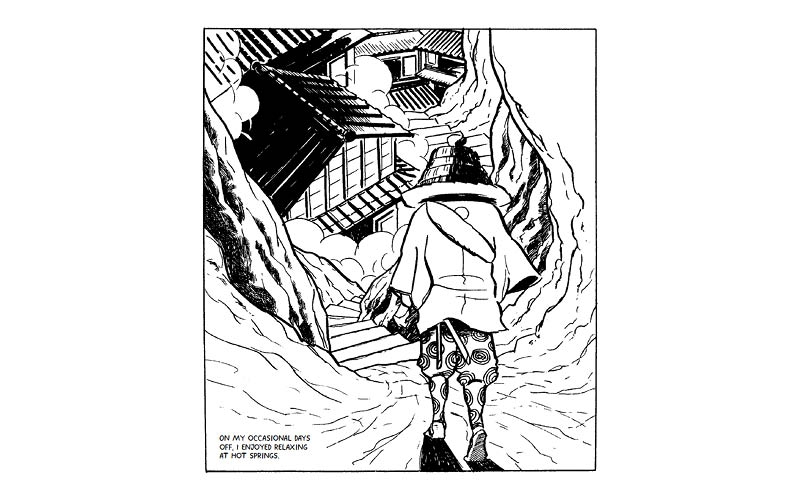

The first story, “The Phony Warrior,” concerns a samurai who, while visiting a hot spring, comes across another samurai whose swordsmanship and athleticism far exceeds his own. Indeed he seems so masterful, that he and other onlookers wonder if he might even be the great Miyamoto Musashi. He is not, it turns out, but merely a charlatan of sorts who awes vacationers with his skills for a bit of cash from the hotel proprietors. Yet our narrator cannot help but feel some pity and admiration for a man who has to use his considerable skills to fool people into thinking he is someone else in order to survive.

Tsuge’s characters often live on the bottom rungs of society, grasping for some sort of success, financial or otherwise. In “Watermelon Sake” a pair of broke samurai think they’ve come across a scheme for sure wealth, but, the narrator confides, “history provides no record of these two men getting rich.” In “Destiny,” a hard luck couple despairs of making ends meet, much less being able to raise children, until an unexpected and tragic death provides them with both opportunities.

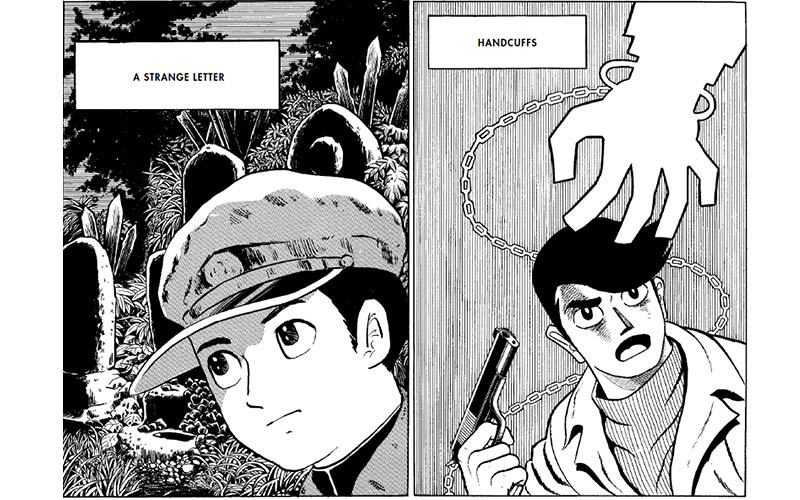

The final third of The Swamp consists of redrawn versions of genre-based stories Tsuge originally did for the rental market. These are largely narrative-driven action and crime-flavored tales that offer an intriguing twist or denouement. In “The Ninjess” a cold-hearted lord takes his would-be assassin for a bride, only to get an unexpected comeuppance years later. In “Handcuffs” a detective must regain his memory to locate the crook he inadvertently left for dead.

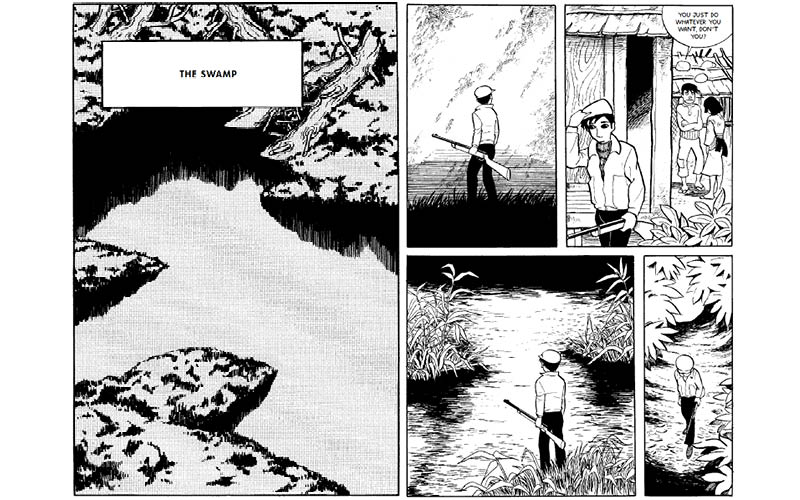

But it’s the middle third of the book that points in the direction that Tsuge would be heading. These three short tales abandon a straightforward narrative for something more elusive and even occasionally surreal. The titular story is about a hunter, ostensibly from the big city, who comes across a mysterious young rural woman. She offers him a place to stay, next to the pet snake she keeps in a birdcage. At night, she says, the snake comes out and strangles her, an act she finds pleasurable. That night the man attempts to choke her himself, only backing off in horror when the woman releases a moan of pleasure. The story ends without any clear resolution, with the man firing off his gun in the swamp, no doubt in a fit of sexual frustration and anxiety.

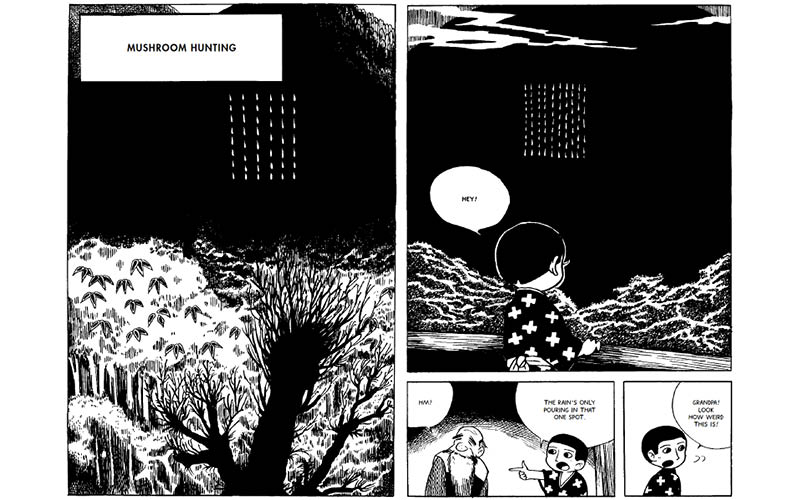

But it is “Mushroom Hunting” that’s the most peculiar, contemplative and by comparison striking tale in the collection. Here, a young boy is promised by his grandfather that they can head to the forest to pick mushrooms in the morning, after the rains. The boy looks out over and sees an optical illusion — the rain pouring only in one spot, which Tsuge draws as a small square of short verticlal lines. The boy is so anxious for tomorrow that he is unable to sleep, and the clock looming over his bed becomes larger and somewhat menacing. And when morning comes, we find our young protagonist has managed somehow to squirrel himself inside of it, perhaps to get closer to the passage of time itself. Or perhaps the clock has consumed him. The story blends shadowy, detailed backgrounds with the almost abstract figure of the child, suggesting not just Tsuge’s later art in works like “Screw-Style” but also the work of later Garo cartoonsits like Seiichi Hayashi, Sasaki Maki and Tsuge’s own brother, Tadao Tsuge.

The lethargic, layabout samurai seen in The Swamp serve as precursors to the central character in The Man Without Talent. This nameless protagonist, loosely based on Tsuge himself, is a manga artist living in poverty with his long-suffering wife and young child. Having seemingly abandoned comics, he looks instead for alternative methods of income, preferable ones that don’t require much effort and result in easy money. So he takes to selling odd-looking stones he finds by the river, in the hopes of attracting collectors or those with a unique eye. He discovers from some equally disheveled older men, there was once a market for stone collecting but that has long since dried up and now it is “a hobby of the aged” (again any allusions to the art comics scene is surely just a coincidence).

As the man meets one disgrace after another — an attempt to sell stones at an auction ends with him losing money; an attempt at a family vacation goes all pear-shaped; an early venture at repairing and selling old cameras (something Tsuge actually did) leads to failure — he meets other dissolute characters much like himself. And often they have tales to tell of other, even less fortunate figures. There’s the down-on-his-luck bird seller who reminisces about the strange man who seemed to have an incredible talent for catching birds, especially cranes. And the bookseller who can barely get out of bed but loans him a book about a (real-life) poet whose alcoholism and vagabond lifestyle led to patrons turning him away and eventually an early death.

All of these men, Tsuge seems to be suggesting, are without “talent.” The unanswered question is what exactly he means by “talent”. By the end of the book we realize that it is equivalent to “usefulness.” That is, a willingness to play by society’s rules and do what’s required. Smile more often. Engage with others. Be a willing cog in the machine. Climb the capitalist ladder. These stories were published in the late 1980s, during and rise and subsequent crash of the Japanese economy, and it’s not too difficult to see the book as a rebuke of sorts to the go-getter mentality present in both the West and East at the time. (Indeed, as editor and translator Ryan Holmberg note in the book’s essay, once Japan’s bubble burst, Man Without Talent became a bit of a fad, and was adapted into a movie, with various unrelated spin-off books offering guides to proper loafing.)

But our man sans talent isn’t raging against the machine. Indeed, he often seems at times to wish the same riches and security everyone else does. It isn’t merely stubbornness and class pride that prevents our protagonist and his loose cadre of friends from being “useful,” but their innate personality. Phrases like “social anxiety disorder” were not in vogue in America or Japan back then, nor was depression considered the crippling mental illness it is today, but it is clear that our man suffers from both. “Oh, how I would love to be buried in antiques,” he says at one point, daydreaming of running a second-hand store. What he perhaps dreams of most is a life devoid of interaction and obligation. And while Tsuge might romanticize such wishes — probably because they are his wishes as well — he’s not so naive as to ignore the effect this sort of retreat has upon the wives and children in one’s sphere. (Which is not to say that Tsuge could be labeled a feminist. The women in his comics — at least as seen here — tend to be either sexualized demons eager to pounce on some unsuspecting man or nagging shrews, even if their nagging is well justified.)

After Man Without Talent, Tsgue retired from cartooning completely. At age 82, he reportedly embraces a quiet existence at his home, west of Tokyo. According to Holmberg, he will often disappear without warning, leaving editors and friends scrambling to locate him. The Man Without Talent ends with our protagonist and his stone stand fading into the mists. Perhaps Tsuge would like to fade in a similar manner, but his work cannot — it continues to attract praise and attention all these decades later (this year’s Angouleme Festival in France featured a large exhibit of his work and Tsuge himself attended to receive a career retrospective prize). The good news is that those of us in North America are finally getting to see just how much considerable talent is housed in this unique cartoonist. •