Çukurcuma is an unusual neighborhood on the European side of Istanbul. Though quite central, just a short walk from the Bosporus or Taksim square, it has survived the recent wave of modernization: its many wooden houses in different colors give it a similar aura to the photos taken some 50 years ago, except that the cobblestones have mostly given way to more modern paving. Antique stores are typical for this quarter, and over the past couple of years, gourmet coffee shops have sprung up on almost every block. Then there are the cats: they are ubiquitous, dreaming their days away on car roofs. On the corner of Çukurcuma Street and Dalgiç Street, just a few blocks down from the hammam, there is a house that fits in perfectly — and yet it doesn’t. It has an unusual dark red color, and the windows hint at the fact that no one actually lives here. There is something otherworldly, almost ghostly about this house, especially during evenings and nights when it seems abandoned in the dark.

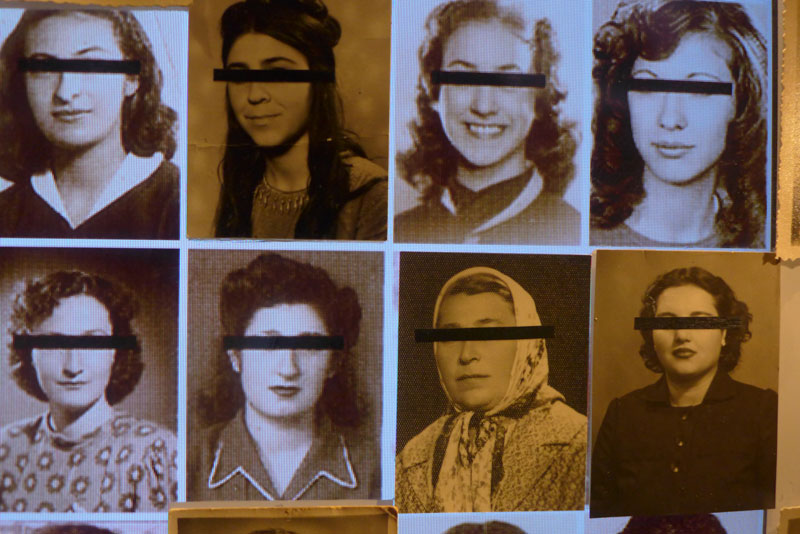

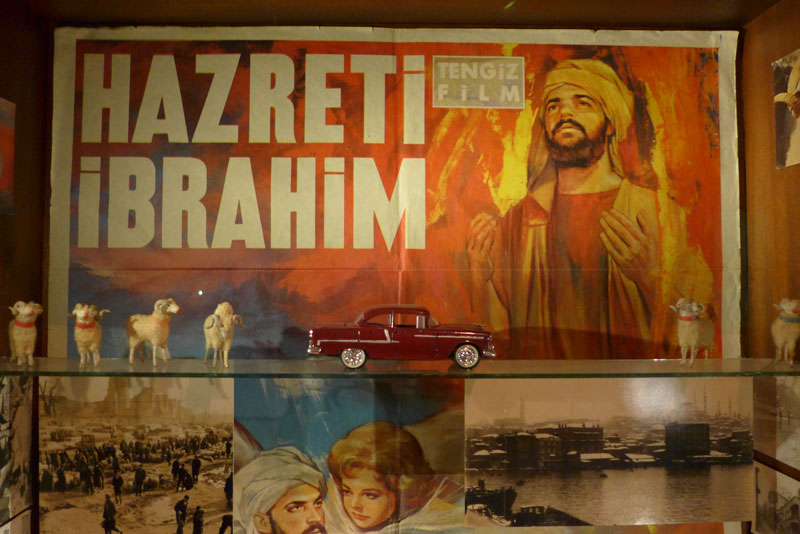

As soon as you enter you realize that this a rather special place, a museum. The building has five flours. And on each floor you discover a wealth of objects, carefully hidden behind vitrines: lipsticks, a girl’s shoe, ceramic dogs, soda bottles, old cologne bottles, vintage photographs of people long forgotten, toothpaste, and false teeth in a glass of water. There is an old taxi meter — “To activate the meter, the driver stretched his arm from where he was seated to lift the red lever, but this was rarely done…”. One cabinet has photos of footballers hanging on almost invisible threads, conjuring up a dream-like scene. Every one of the 83 cabinets offers a surprise with its mixture of memorabilia and bric-a-brac. This is nature morte. Sometimes there is a clear link between the name of the cabinet and what can be seen inside it. For example “The First Seeds of My Collection”: a collection of hair sponges. At other times the link is rather cryptic and works by association: “Happiness Means Being Close to the One You Love. That’s All.” The cabinet consists of a black-and-white photograph of the Bosphorus in the background, a ceramic ashtray, and a few objects that appear to have been randomly assembled. Some come with short video displays, others with soundtracks to create the atmosphere of a specific situation. And it is tempting to read a story into them. One of the displays has numerous photos of women with black lines drawn across their eyes: this refers to a once standard and from a contemporary perspective hardly believable practice by Turkish newspapers to expose women who had committed adultery, were prostitutes, or were victims of rape. Watermelons, sardines, eggplants, cheese, and other foods have been molded in plastic.

Once you have seen the Museum of Innocence and its often curious displays, you may turn to Pamuk’s 2008 encyclopedic novel by the same name. In fact, the museum and book were conceived together. The relation of the things you have seen in the museum becomes clearer. The displays basically follow the story, and each display corresponds with one chapter. In the novel the narrator, Kemal Basmacı, describes his growing obsession with Füsun, a distant relative from a lower-middle class family living just north of the Golden Horn. He begins to collect things and even steals them from Füsun’s home. For eight years he keeps inviting himself for dinner — some 1,593 times — to have countless glasses of rakı, the anise liquor somewhat similar to Greek ouzo or French pastis. As much as the book tells this story, the museum is a homage to Kemal’s one-time lover. Their love remains unfulfilled because Füsun is of lower standing.

There is a very peculiar atmosphere about this museum: it is saturated with hüzün, the Turkish word for melancholy. But melancholy in a very complex form, evoking failure, deep loss and grief, a longing for a world that no longer exists and which you are not sure you really want back. Maybe one day a young academic will take on the challenging task of comparing hüzün with the Portuguese idea of saudade. Furthermore, the museum illustrates how conservative residents of Istanbul appropriated Western values and products at the time: in this sense the museum teaches a lesson in haute-bourgeoisie, Turkish style. It is also a document to the ambition and obsession of a writer and collector, and to the passion of a cultural anthropologist of the everyday.

There was a small group of cabinets I liked best: “The Cinemas of Beyoğlu,” “The İnci Patisserie,” “The Grand Semiramis Hotel,” “Summer Rain,” “Journey to Another World” — names that evoke the mood of a bygone era. What they have in common is that they are all hidden behind a curtain, its color in perfect harmony with the color of the building. So the contents, if there are any at all, are invisible for the visitor. Will they be disclosed at some point or do they retain their mystery? The largest display is made up of 4,213 cigarette butts, some marked with lipstick traces, covering the entire rear wall of the entrance hall, each one of them supplemented by some notes in Turkish. Each cigarette has supposedly been touched by a girl named Füsun.

Along with the museum comes a “Modest Manifesto for Museums” which does nothing less than overturn most of the principles that other museums are based on. “The aim of present and future museums may not be to represent the state, but to recreate the world of simple human beings — the same human beings who have labored under ruthless oppression for hundreds of years”. To conclude, the writer and Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk writes: “The future of museums is inside our homes.”

The now dark-red house was built three years after the earthquake in 1894, most likely by an Armenian foreman. The upper level hosts the room in which Kemal Basmacı lived between 2000 — the same year that Pamuk bought the house — until his death on 12 April 2007. This is where Pamuk came to talk to him and take notes while Kemal lay down on the bed and stared at the ceiling. When Pamuk wasn’t talking to his friend, he was busy scouring the inventory of antique dealers and junk dealers in this neighborhood and beyond, and preparing the 1,000 objects for the display (cigarette butts not included, just the intricate order in which they were set). The museum finally opened in 2011, and cost Pamuk roughly the same as he received for the Nobel Prize for Literature: $1.5 million. As opposed to many if not most other museums, the building itself has been far more costly than the objects on display.

There is a complex interplay of history, place, and identity at work here. As Pamuk explains, both the novel and museum are about both his and Kemal Basmacı’s lives: “I could easily be Kemal. I could tell my story as if it were his, and his as if it were mine. And every time I realized this, I felt that it didn’t matter too much which voice was Kemal’s and which was mine. Did the objects not remind us both of the very same things?” The stuffed crow that can be seen in one of the museum’s displays recalls Pamuk’s nickname Karga: the Turkish name for this bird. Pamuk himself grew up in the affluent Nişantaşı district, on Teşvikiye Street, now a high-end shopping street, a few miles further north. And his grandmother spent the last 30 years of her life in a single room in a house the size of the museum: “The rooms that had once been home to an animated, joyful, crowded family life were now under an inch of dust, but the objects that furnished them had been perfectly preserved. Whenever my older brother and I used to walk into these eerie, quiet rooms, we always felt with a shiver that the objects were communicating with each other.” This is from the novel, but it’s as much a story about collecting and saving things from oblivion as it is about rescuing memories from the past, from a time when Istanbul had roughly one or two million inhabitants, not the 15 or 17 million it has today. For the reader it is not always clear where the boundary between fiction and (imagined) reality is.

I can hardly think of a place where you feel further removed from contemporary Istanbul with its new Dubai-like shaped skyscrapers and high-end shopping malls. You don’t have to have read the novel to appreciate the museum, as both are works of art that function both together and independently, but you may as well read it. And if you read the book first, you can bring it to Istanbul and you will be allowed to enter the museum for free. Even if you didn’t get beyond the first 50 or 100 pages of the book, you may still feel attracted to the peculiar ambiance of the museum. Just don’t tell them. •

Photos by the author. Quotations from Orhan Pamuk, The Innocence of Objects (Abrams, New York, 2012).