The deaths of half a million people. A year spent in isolation, living on crackers and popcorn that Amazon delivered, wearing the same two dresses day after day. Because I never left the house, squirrels began to make nests in the engine of my car. Relationships dropped away. I watched endless Scandinavian crime shows, became lazier and lazier. Dust moats grew in the corner of each room in the house; soon it was like living in the sleeve of a mohair sweater. Entangled in endless loops of worry, my sleep suffered. I was supposed to be finishing a novel but could not focus.

Natasha Rajah, a professor of psychiatry at McGill University who specializes in memory and the brain, was, in Sarah Lyall’s “We Have All Hit a Wall,” attributed to saying “The longevity of the pandemic, endless monotony laced with acute anxiety, has contributed to a sense that time was moving differently, as if this past year were a long hazy exhausting experience lasting forever.”

Heartsick for family, needing to belong to someone, something, in the early spring of 2020 I picked up a quilt to repair that had been stitched by my great-great-great-grandmother Sarah Graves, who crossed the country in a covered wagon as part of the Donner Party. Maybe I needed to look backward because I couldn’t look forward, but the moment I began to sew, with only one single piece of thread, I was flying back through time, landing in the lap of a young woman long perished.

The story of the Donner Party holds patriotism, murder, racism, and insanity. In 1846 the footsteps of my great-great-great-grandmother pulled the hem of America from one side of the country to the other. Eventually, when California became a state, pioneers added one more star to the flag. These pioneers were ordinary people, farmers, homemakers, tradesmen, families with children, many newly immigrated from Ireland, Germany, Poland, Mexico, England, and Belgium who decided to load their households into covered wagons and cross the country on foot, hoping to acquire free land in California and begin a new life. Some of the wagons in the Donner Party followed a shortcut advertised by a lawyer named Hastings who promised to cut off 300 miles through the mountains. It was not a shortcut; they were left to starve to death at Donner Lake entombed by an early winter’s snow. Many of the stranded, in order to survive, resorted to cannibalism. Sarah Graves lost her mother, father, and her husband that winter. Two Miwok Native Americans who served as guides for the group were murdered and eaten.

I don’t know exactly when my great-great-great-grandmother sewed this quilt, but it is woven with memory, time, the geography of America. It is a simple design of blue and white squares, incoherent fragments that she has stitched into something beautiful. A dry immutable fragrance rises from the cloth, the scent of time itself. Some of the squares are soft, slightly frayed at the edges. Like the sound of her footsteps walking across America, one stitch follows the next, rimming the fullness of color, the fullness of time.

Late spring, 2020. The virus had moved from one continent to the next. Bleaching packages, washing our hands, we were all becoming more frightened.

You leave something of yourself in the things you make. I like to think of my great-great-great-grandmother threading her needle in the firelight that winter, trying to stitch her way towards hope. Some palpable presence of her is sewed into this quilt, the miles walked, the meals made, the people mourned, time, mortality, beautifully observed. Long after her children have died, long after her children’s children have died and the suffering of that winter has become only a footnote in American pioneer history, this quilt lies across the lap of her great-great-great-granddaughter, goodbyes and loss woven into each stitch.

Some days, other than the conversation I have with my husband over a cup of tea, a small comma of light we shared each day, my great-great-great-grandmother was the only one I talked to, each pull of the thread up through my needle connecting me with her lively strand of DNA. Is it because we both have asked the same question: who was coming to save us? I imagine her, this woman who has made me, trying to forget what she had to do to survive, trying to live only in the regulating rhythm of her tiny stitches, the miniature rise and fall of the needle.

What was it like for her to eat flesh from a body who only yesterday she had called by name? Was she already thinking as a mother, the children she would make if she survived, who would make more children, who would make more children who would eventually make me?

Does she need to be forgiven?

I began to go through piles of old family history and discovered a letter she had written to her uncle and aunt. “It is with a heavy heart that I sit down to inform you of our mournful situation. I cannot enter into the details of our sufferings; I can only give a brief account. We got on very well till we got to Fort Bridge, there we took Hastings Cut Off and became belated, and caught in the California Mountain without any provisions except our worked down cattle and but few of them. They erected cabins and killed the cattle, but there was not enough in the company to last half of the winter, and no game.” The matter-of-fact tone in her words matched her matter-of-fact tidy stitches.

May rolled into June. Waiting for deliverance, every day now I reached for the quilt. The small stitches punctured the waiting. At least the wildflowers did not have to wear masks. They had never been so beautiful. My stepdaughter, with whom I am close, gave birth to a little boy. I could not visit him, kiss those little puffy knees. Barely any airplanes overhead in late spring. Sometimes at night, the sky swept clean of human occupation, I got a feeling I had no name for. As though that great space has swallowed our voices, even our 8 o’clock howls to acknowledge the first responders seemed fragile, a tiny barricade against our fear.

Longing for connection, family, love really, I floated disembodied through my days, the distance between the life I used to have and the life that was now growing wider by the day. I began to experience a new and different kind of loneliness, one I had never felt before, a kind of existential shudder. What was going to happen? Who was going to save us?

I was living my great-great-great grandmother’s sense of time, boredom laced with worry. The particulars of the day were not the same, but the fear and the waiting was the same. After walking the continent, less than 150 miles from Sutter’s Fort, Sarah Graves waited for rescue. I wondered about the colors she chose for this quilt. Blue and white. Did she choose blue because she had not seen the sky for those many months? Did the white represent the snow that imprisoned her? There seemed to be a deliberate interplay between what is and what could be, the silence and doom of the white against the jubilant blue sky.

It was summer. Terrible forest fires in California drawing near to our home. I kicked the squirrels out of the engine of my car and packed my most precious things in the backseat. My own covered wagon. Deaths from the virus climbing. Everyone knew someone who had died. No mules packed with cornmeal and dried venison struggling over the mountains from Sutter’s Fort to Donner Lake. No rescue.

Making meals, going to sleep, waking up, the circular rhythm of our days repeated endlessly until we were almost erased by the monotony. The days, bland in their inertia, fell into each other, one after the other. Though time was moving I felt encased in the resin of boredom, the never-ending days always the same. Trying to penetrate the thick turgid air with my needle, I reached for the quilt most mornings. Some days it was the only thing I did all day that was careful and precise.

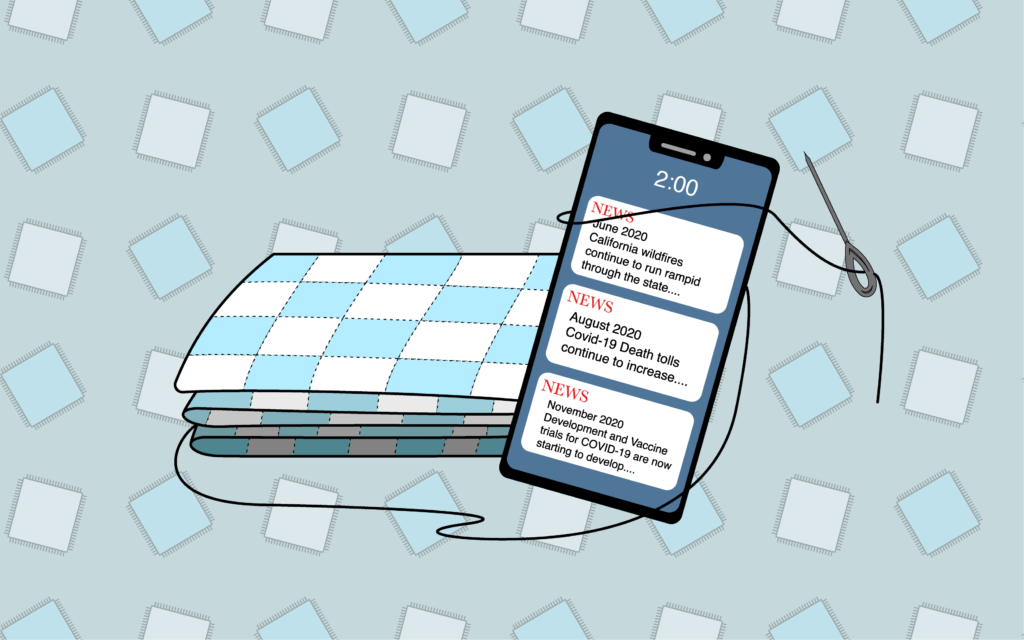

I learned a new phrase. Doomscrolling. Every morning, as if they were tarot cards I could slap down to try to read the future, I searched the news sites. Every day, worsening news. More lockdowns, more deaths. We were under siege, but our enemy was invisible. When was this pandemic going to end? The things I had taken for granted, the expressions on people’s faces, the feeling of a hug, the sound of different voices, the taste of different food, all this had left.

It is a strangely intimate conversation to repair a quilt made by a woman who lived so long ago, caring about the same thing she did. Some days the quilt seemed alive with her breath. Folding a piece of blue cloth under, tacking it into place, the steady footsteps of stitches, the rise and fall of the needle, I did not hear her thoughts so much as I felt her will. Separate, the blue and white scraps are one thing, together they are repurposed into a pattern of geometric hope, the future shining from the folds between each patch of color. More eloquent than a letter, more poignant than a message in a bottle, the quilt became a magic carpet ride that flew me back into time, history not just romantic folklore or museum curated pieces enshrined in Plexiglass. Some days when the world seemed to have fallen into broken pieces and everything seemed chaotic and fragmented, I picked up the quilt with the entreaty of prayer in my throat, hoping, like the quilt, the world would come together to fight the virus, see the beauty of the whole, not just the broken pieces.

Fall, 2020. News of Pfizer and Moderna developing a vaccine, fast-tracking it through approval.

As I stitched my way through autumn, I began to receive what language can’t always reach. Love, joy, rose up through my needle, along with turbulence and fear. Most days I lived in the blue sky of hope. Some days, weary, I trudged through the snow. Sometimes, as my great-great-great-grandmother must have done, I could stand back and see the glorious whole, sometimes I lived only in the micro granular, the rise and fall of the needle.

Winter, 2021. Capitol riots. A dear friend of ours had the virus, experienced almost a psychotic break, forever altered by this strange disease. Another friend returned from London, months later still plagued by errant weakness.

December 16, 1886. 12 men and five women, one of whom was my great-great-great-grandmother, set out on the Forlorn Hope expedition to try to reach Sutter’s Fort and bring back food to the ones left behind at Donner Lake. “We were 150 miles from the settlements with snow thirty feet deep to cross,” Sarah Graves writes. “They made snowshoes, and 16th of December, father, Mary Ann, my husband, myself and eleven others set out, with about eight pounds of dried meat, without knowing the road; on the eighth day of our travels we got lost but resolved to push on, for it was but death any way.”

Sarah Graves was 27, her husband was 23 and her father was 57. 14 out of the 17 wore snowshoes fashioned by Franklin Graves, Sarah’s father. “It rained that day and night and then snowed for three days and all of this time we were without fire or anything to eat. Father perished in the beginning of this storm of cold; four of our company died at that place.” Sarah’s husband died sometime in the night. “On the night of the 6th of January, my husband gave out and could not reach the camp; I stayed with him without fire; I had a blanket and wrapped him in it sat down beside him, and he died about midnight, as near as I could tell.” Sarah Graves untied the black handkerchief from his neck that he had used to ward off snow blindness, tied it around her neck, stumbled towards the others. “Don’t hurt him,” she said, already knowing what they were going to do. They didn’t listen. “As soon as the storm ceased we took the flesh of the bodies what we could make do us four days, and started.”

Stanton went blind. They left him smoking his pipe. Mr. Foster tracked down the two Miwoks who served as the Forlorn Hope Party guides and shot them. Not looking at each other they ate their flesh.

Now only seven remained. January 16, 1887. Sarah Graves stumbled out of the mountains. January, 2021. Vaccine rollout began.

Almost an entire year spent in isolation. The quilt was finished. Superstitious about the ghosts that might slip into my dreams, I hung it across the room so it was the first thing I saw in the morning.

Stitch by stitch this long, long year, I pulled lessons up through a quilt sewed by a woman who lived 175 years ago. Some days, living next to the soon to come, I stayed only in the granular, did not raise my eyes too far, while other times, I stood back and saw how my great-great-great-grandmother had brought order to a world of scraps. Repairing this quilt during the pandemic taught me how to wait, taught me as well how to live with the unknown. Reaching into the past brought me into the present, the infinitesimal fleeting now, reminding me that beauty carries its own particular form of immortality.

Sarah Graves’s story is not mine, it is hers, but I am her echo. I pass her story of survival up and through me, writing her memory but living her future. “Live,” she told me through the thread. “Love. Survive. Sew this quilt, write these words.” •