In a certain way, Punpun seems like a normal, if rather put-upon, kid. Sure, his dad is an abusive ne’er-do-well who abandons his family and his mom is a neglectful lush, but Punpun himself seems like a rather average, likeable youth. He craves sweets, is both curious and terrified about sex, enjoys hanging out with his friends, and pines arduously for Aiko, the cute girl in his class.

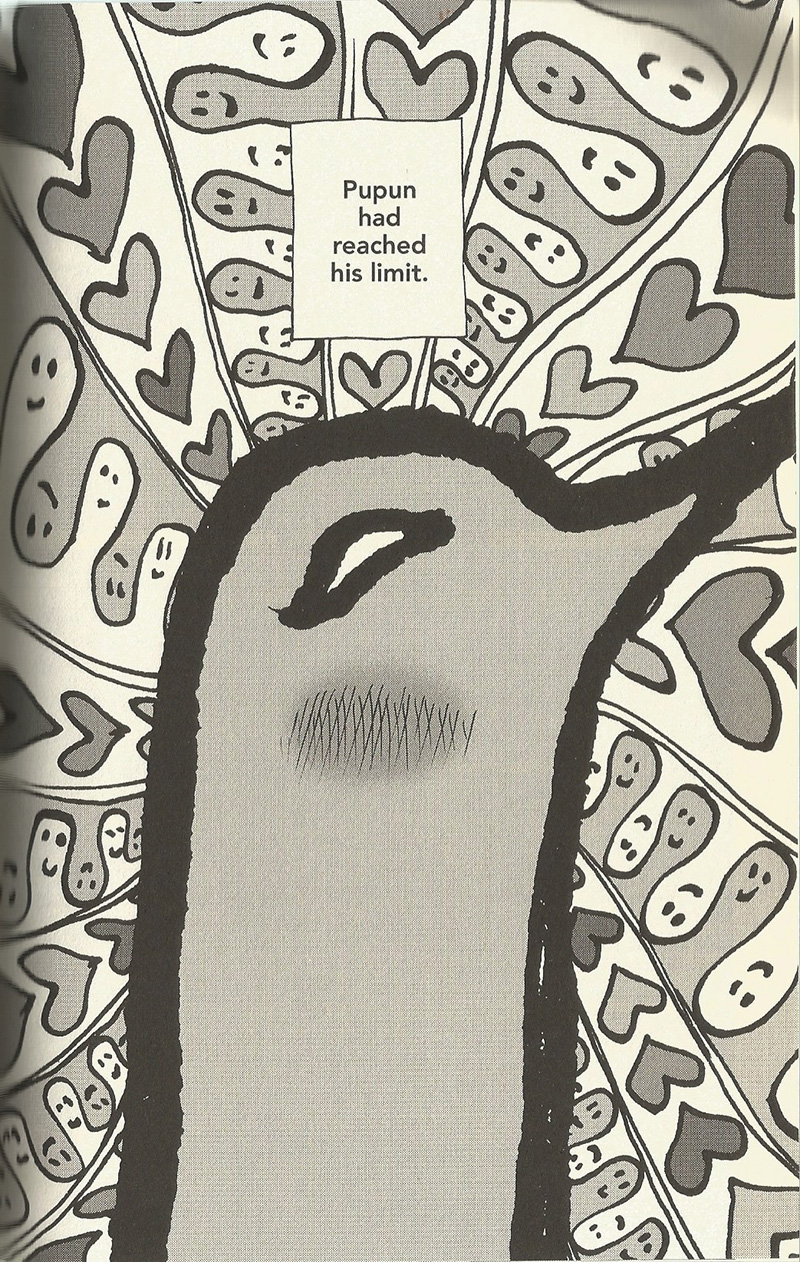

Of course, one glance at Punpun will instantly show you what separates him from the rest of the crowd. Unlike most of the cast in Inio Asano’s Goodnight Punpun (two volumes thus far), who are drawn in a relatively realistic fashion, Punpun and his immediate family are delineated as what could best be described as little bird ghosts: two stick legs, an upside down U for a body, two dots for eyes and pointy little beak nose — a childish scrawl interacting with a photorealistic world. It’s not necessarily the most original way to convey a character’s alienated relationship with society, but in Asano’s hands it remains an odd and striking method.

Surreal narrative devices aside, however, Goodnight Punpun, along with another newly translated work, A Girl on the Shore, further solidifies Asano’s reputation as a creator of note and cements one of the central themes in his manga: the struggles of adolescence and young adulthood, especially in relationship to the outside world.

Asano first came to prominence in Japan with the 2002 release of What a Wonderful World!, a collection of short stories – some of them interrelated – about a restless group of city dwellers: disaffected 20-somethings, bullied school kids, small time gangsters, and more, all in the midst of (or contemplating) rash, life-altering decisions. From the start, Asano had a sharp eye for the rhythms of everyday mundanity, but suffused it with dollops of magical realism in the form of the occasional ghost or talking animal.

His 2006 work Solanin continued in a similar vein, though minus the ghosts and verbose crows. In that comic, a young woman, Meiko, struggles with the demands of adulthood and the fear that she will be incapable of doing something meaningful with her life. The book received high praise both in Japan and here in the U.S. (it was the first of Asano’s works to be translated) but it delved a bit too close to sentimentality for me, particularly with the sudden tragic plot twist two thirds of the way through the story.

I’m more drawn to his 2003 work, the surreal and dark Nijigahara Holograph. Here, Asano abandons some of the more uplifting themes contained in Solanin and What A Wonderful World to tell the story of a group of adults marked by a violent, tragic incident that took place in their childhood and continues to haunt them in ways don’t necessarily comprehend. Asano adopts a nonlinear format and remains enigmatic on several key points (one integral character doesn’t show up until the very end), throwing in haunting, eerie images along the way. It’s a puzzle that never completely reveals all its secrets but bears repeated reading anyway.

That surreal and disturbing atmosphere continues in Goodnight Punpun, though Asano leavens those aspects with a good dose of (dark) humor. Begun in 2007 but not completed until 2013, the manga follows Punpun as he ages from elementary school to adulthood and attempts to navigate the world with only his feckless uncle to help him (though the uncle has his own unique neurosis to stew in).

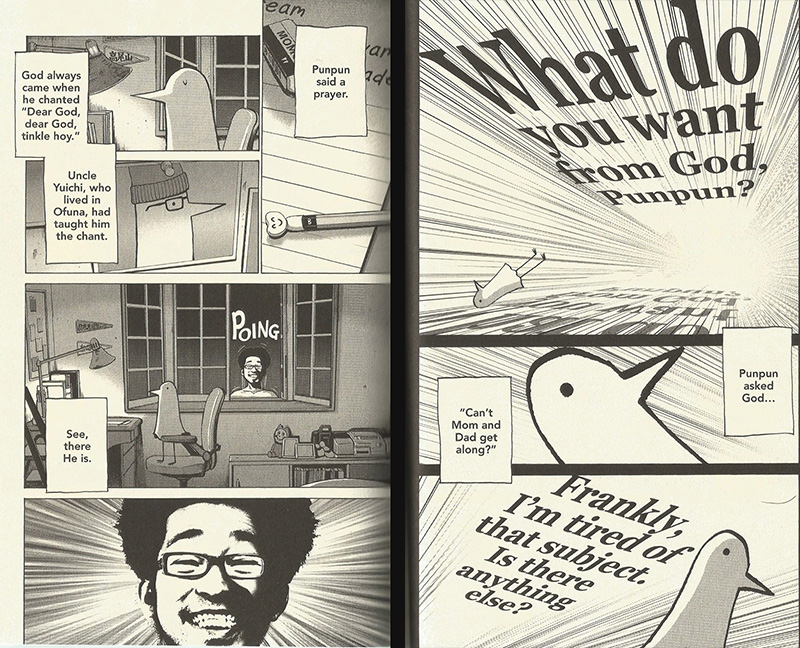

There are other oddities lurking in Punpun’s world beyond his doodle-like appearance. For one thing, Punpun frequently converses with “God,” a floating, grinning head that does little beyond offer bad advice or insults. Punpun himself hardly speaks, though a storybook-style narrator fills in the conversational details (“Punpun was truly saddened that God couldn’t come up with something sensitive to say”).

What’s more, all of the adults in this world wear grotesque, fixed expressions, as if they’re desperately hiding awful secrets, and engage in odd or childish behavior. The principal and head teacher, for instance, giddily play hide-and-seek on the school grounds, while Punpun’s teacher screams and bangs his head on the desk when Punpun doesn’t turn in an assignment.

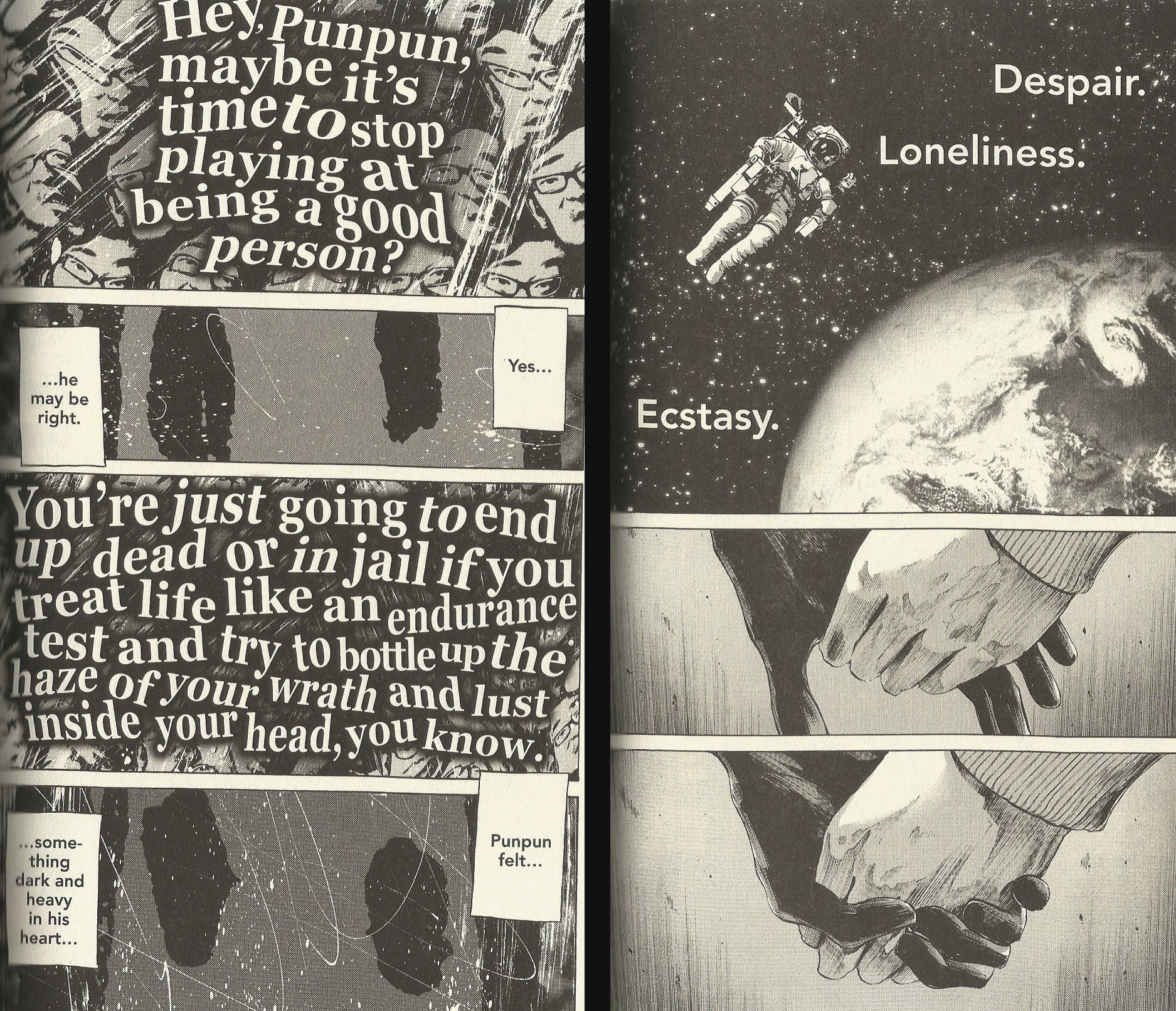

As the story progresses, more unsettling things peek out from the corners. Punpun and his friends stumble across a porn film that contains a confession from a man who claims to have killed his family. His uncle’s seemingly sad-sack backstory indirectly involves child abuse, betrayal, and attempted murder.

While many of the characters in Asano’s other manga are often grasping to attain some sort of happiness or contentment, here Asano seems to be asking if happiness itself is even attainable. Punpun’s stumblebum attempts to win Aiko’s affections are charming, but he’s surrounded by examples of not just love gone wrong, but obsessive love that leads to disaster (obsession in general haunts the fringes of Punpun’s universe; one of his friends becomes so adept at badminton that winning encompasses his entire being). In this world, there’s no way to get through life without becoming damaged. And if you’re damaged, how can you ever truly find love and happiness?

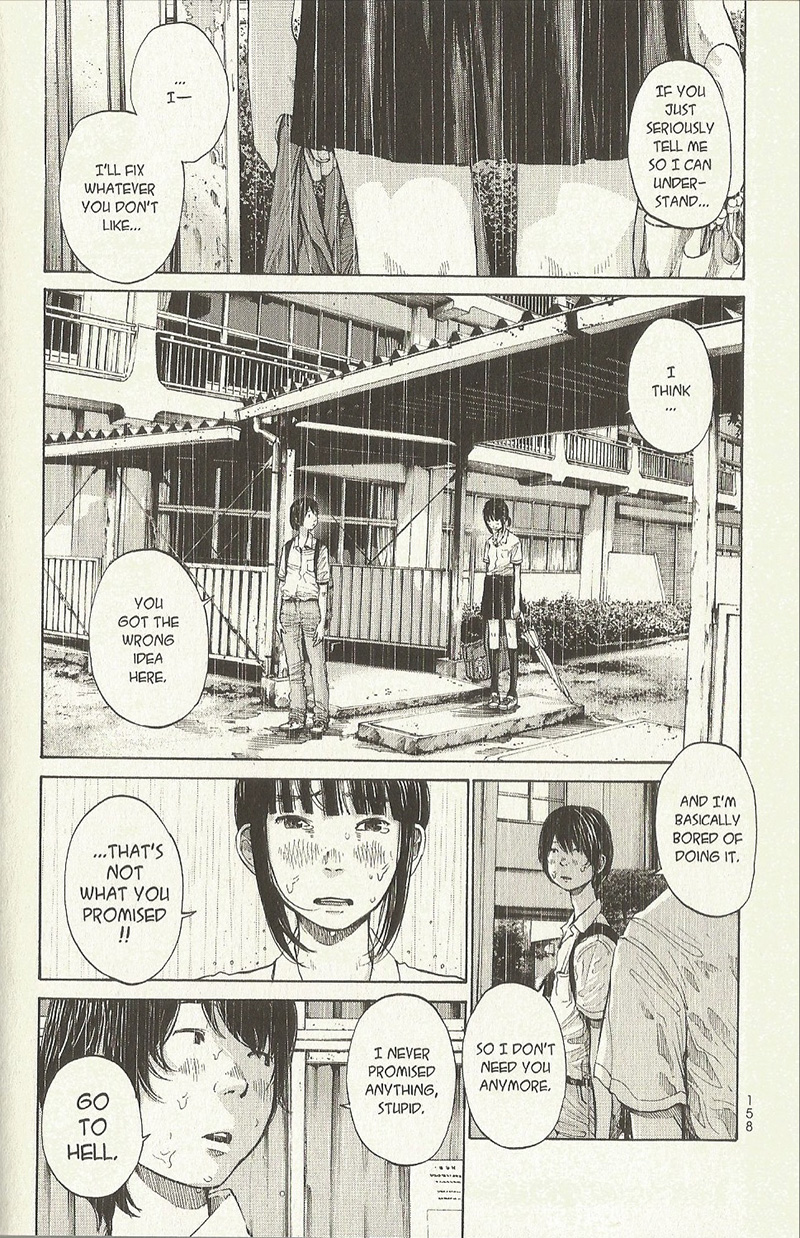

While Goodnight Punpun indulges in all manner surreal imagery and narrative tricks, A Girl on the Shore (originally serialized 2009-2013) is presented in a more straightforward and realistic manner. Gone is the magical realism. Instead we have two teens, Koume and Keisuke, who begin an affair in a quiet seaside town.

Despite their young age, both Koume and Keisuke are dealing with some emotional baggage. The former is coming off the heels of a bad dalliance with the aloof school playboy. The latter, a sullen loner, bears even deeper scars, most of which are revealed as the book progresses (and I wouldn’t dream of spoiling).

The relationship begins with both swearing their relationship is purely physical and that neither is looking, though Keisuke claims to be more infatuated with Koume than she is with him. Haltingly at first, then with more ferocity and adventurousness, they begin having sex, all the while continuing to avow that they have no real feelings for each other, desperately trying to be more mature and “adult” than they truly are.

The most striking thing about Shore, at least initially, is how sexually graphic it is. While hindered to some degree by Japanese censorship laws (Keisuke’s penis is a white, glowing phallic symbol, devoid of details) Asano clearly has no problem drawing the couple’s, er, couplings, often in a matter-of-fact, direct manner that underscores the pair’s curiosity with sex than with each other. (It is also worth noting that Asano steers clear of cliché in his portrayal of Koume as a young woman who willing to divorce love from sex.) Still, those who feel a bit skittish about watching 14-year-olds copulate might want to look elsewhere.

To see NSFW image, click here.

The frankness doesn’t just extend to the sex scenes, but in their dialogue with each other. Both Koume and Keisuke are exceedingly cruel to each other (Her: “I like your dick better than you. It’s not constantly grumbling at least.” Him: “The truth is you don’t have any friends do you? Go to hell already.”), attempting to be as dismissive or aloof about their relationship as possible rather than risk revealing any feelings, either about each other or themselves. Such revelations inevitably tumble out by the story’s end, however, though not necessarily in the way you’d expect.

While a good deal of Asano’s previous work (at least what’s been published in North America) focuses on emotionally damaged young people struggling to find purpose, Goodnight Punpun and Girl on the Shore specifically seem concerned with the way love and relationships can both further afflict and occasionally repair those people and perhaps alter their struggle completely. It’s to his credit that Asano is sharp enough and has enough of an ear for how people talk and interact to steer clear of mawkishness even when trying to sustain a moment of grace. One false move and either of these works could fall into the worst sort of trite melodrama. That both comics are so wildly divergent in tone and style only heightens my estimation of Asano. In the end we can’t help but feel for Koume, Keisuke, and Punpun, partly because we know their struggles will not end without pain on their part. And partly because they’re just a bunch of crazy, mixed-up kids. Or bird-ghosts. •

Images courtesy of the author, Viz, and Vertical.