For several decades many readers of modern American poetry have believed that Countee Cullen was a lesser poet than Langston Hughes. This judgment is rather sharply at odds with how the two poets stood relative to each other during the Harlem Renaissance. Large numbers of readers in that period — from the elite to the newly enlarging community of “common readers” in the African American population — admired both men. Hughes himself described his status as that of the “poet low rate,” punning on the unofficial title of “poet laureate” which he gladly ceded to Cullen. The joke at once mocked the notion of laurels, and yet demonstrated that such categories had their social and literary critical function. But despite all the distortions (more of which in a moment) involved in assessing laurels and their correct bestowal, we can learn something about African American poetry and its merits and context by rehearsing the difference as well as the affinities, elective and natural, between the two men.

It is important to remember that Hughes and Cullen were for a while very close friends. They introduced one another to important critics, such as Alain Locke, and they shared a great many enthusiasms — most importantly, perhaps, a love of the dramatic arts. They also faced economic stringencies which affected their relationship to their own talents. Both tried their hands at various genres — children’s books, playwriting, and fiction, a few essays — hoping against hope to make something like a living wage. Even when the terms of their friendship were less close, they collaborated on socially conscious projects; this was most evident (though now largely forgotten) when Hughes solicited a poem from Cullen to help support the Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners; Hughes, for his part, helped in some of the rewriting of St. Louis Woman, the musical that held Cullen’s attention for a protracted period, as he contemplated a financial success. (Admittedly, Cullen was wary about Hughes’s gaining more than his just share of any possible royalties. This wariness perhaps resulted from the authorship dispute Hughes engaged in with Zora Neale Hurston over the musical Mulebone.) Both men also knew — and self-consciously accepted — the task of writing poetry when large portions of the country’s social and political sympathies were not available to them.

Langston Hughes on The Smart Set

The Hughes Blues by Richard Abowitz

Of course, Cullen’s temperament differed from Hughes’s in many ways. Perhaps most important as a shaping force was the interest he explored and committed himself to in his life as a student. From the rigorous DeWitt Clinton high school in Manhattan to his year as a master’s degree student at Harvard, he enjoyed exposure to a wider range of poetic instruction than Hughes had been able to enjoy. Cullen’s temperament thrived on instruction: he liked setting models and formats in front of himself as a way to measure and reaffirm his talent. Cullen was the more developed of the two in terms of possessing an articulated esthetic that he could apply to most any possible verse form that came to hand. In May 1924, he responded, with his typical kindness and balanced assessment, to one of Hughes’s poems.

As you must realize, I was very anxious to receive both your letters and the card you sent me — and especially the poem which I consider, while not the best you have written especially good, and most naturally adapted to music. You have a pronounced gift of singing and painting in your work. I would really give anything to possess your sense of color. I am going to send the poem out immediately. I am also going to send you copies of Opportunity and the Messenger in which poems of yours appeared.

This letter was sent while Hughes was journeying around the seven seas and Cullen was working as an assistant editor at Opportunity and writing a column called “The Dark Tower”: his personal commentary on things cultural and literary taking place largely in Harlem. The tone falls between that of envy and brotherhood.

Signs and tokens of friendship sometimes avail, but little. Unless writers have actively collaborated on a major project or over a length of time, the ability to focus on competitive opposition (or jealousy or egregious temperamental differences) lends itself to a more dramatic historical narrative. In the case of Hughes and Cullen, a starkly polarized context was structured by considering their respective attitudes towards poetry in general and poetry for the African American audience in particular. The literary historical facts have generally been marshaled to depict Hughes as a breaker of poetic forms and Cullen as overly beholden to them. As an exemplar of modernism and its many ways of “making it new,” Hughes’s reputation has grown greatly while Cullen’s has become somewhat static and even diminished when compared to what it was in the 1920s and ‘30s. What continues to serve as a crucial contrast in the matter of Hughes and Cullen had become visible in the terms we see today because of the vast developments in African American literature. These developments have shown considerable bias in the direction of Hughes as opposed to Cullen. But some historical reconsideration might illumine Cullen’s worth and his continued meriting of canonical status.

As the foremost of African American poets by common consent, Hughes has justly been given credit for introducing a jazz idiom into his poetry. The appearance of his first book of poems, The Weary Blues, marks an important moment in the large and complex field of African American poetics. Cullen reviewed the volume even as his own first book was entering the poetry world. As was typical of him, the review is modulated but also easy to misread. The main issue centers on whether or not Cullen judged Hughes’s work as lacking in sophistication and therefore working against what was then the high-pressure concept of “racial uplift.” Cullen did not think it wise to concentrate on “low” material, for fear that an unwelcome and distorted stereotyping would be the result. Hughes resented the implication and responded in an essay he titled “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountains,” often pointed to as one of the central texts of the Renaissance. In it, without identifying him by name, Hughes accused Cullen of wanting to write like a “white poet” and thus of wanting to be “white,” tout court. It is, I believe, an unfair charge. Cullen never answered it in a public way. But he addressed some of the figures of the time in an attempt to explain and justify his esthetic valuation of Hughes’s jazz poetry. His outreach included letters to such Renaissance figures as Harold Jackman, Zora Neale Hurston, and Carl Van Vechten.

Jackman was a close friend of Cullen’s, a handsome dandy, and a much-admired raconteur. Cullen wrote to assure Jackman that he never said Hughes wrote “unconsciously” about black people (meaning, I think, that he ignored the issue of racial uplift), and thus he would have expressed attitudes that were better kept private. He even argued that Hughes couldn’t have written “unconsciously” about race, a subject that Cullen introduced into his own poems in every one of the volumes he published during his lifetime. Jackman knew how Hughes’s attack must have stung — a charge that a black person wanted to be white was one of the most serious that could be thrown at another black, especially a writer. (Jesse Fauset made just this charge against Alain Locke after he published a tepid review of one of her novels.) Cullen, some years before, granted a reporter an interview while he was only in high school and there argued that race was a subject that did not necessarily shape one’s attitudes — and practices — as far as poetry was concerned. Cullen believed firmly that a portion of the realm of the esthetic was beyond the depredations of race and race superiority, that one should first of all not be limited to the category of “racial artist.” To be so limited would inevitably limit one’s poetry. This argument was likely the basis of Hughes’s charge against Cullen.

The core of Cullen’s critical judgment could be found in his remarks on what he felt were the way Hughes’s jazz poems constituted a form of self-limitation. This is the main part of the review that Hughes could not accept.

Taken as a group, his selections in this book seem one-sided to me. They tend to hurl this poet into the gaping pit that lies before all Negro writers, in the confines of which they become racial artists instead of artists plain and simple. There is too much emphasis on strictly Negro themes; and this is probably an added reason for my coldness to the jazz poems – they seem to set a too definite limit upon an already limited field.

Here Cullen’s rhetoric slips in a number of places: “hurl…into the gaping pit” is needlessly melodramatic; “artists plain and simple” would be hard to define and distinguish; and why is the field “already limited”? Cullen was working with a set of esthetic assumptions that relegated jazz and jazz poems to a lesser order than that of the high Romantic lyric. Part of the problem is that people would reflexively assume that because he was cold, in this instance, to jazz poems, Cullen would also be cold to jazz itself, which was manifestly not the case. In fact, one can read his defensiveness on these issues as an ambivalent desire to make sure black writers did not end up adapting to the estimates of white readers. Some of such readers were often inclined to see less sophisticated blacks — and black material — as charming or quaint. Cullen wanted the chance to address all readers in the highest possible terms. To be a “racial artist” by treating only black subjects and experience would be to needlessly restrict one’s artistic scope and exercise. This would be what lay beneath the forming of “an already limited field.”

The question of which writers might most authentically use folk or jazz material would bedevil the Renaissance and its commentators for many years. Though much has been written on this topic, in the mid-‘20s opinions on what counted as authentically black poetry had not completely formed. This meant different levels and complexes of authority could be solicited or attacked. Here is what the always surprising, and often combative, Zora Neale Hurston wrote to Cullen about Hughes’s first book and its jazz poems: “By the way, Hughes ought to stop publishing all those secular folk-songs as his poetry. Now when he got off the ‘Weary Blues’ (most of it a song I and most southerners have known all our lives) I said nothing for I knew I’d never be forgiven by certain people for ‘crying down’ what the ‘white folks had exalted’, but when he gets off another ‘Me and mah honey got two mo’ days tuh do de buck’ I dont [sic] see how I can refrain from speaking. I am at least going to speak to Van Vechten.” Van Vechten, a white Negrophile and cosmopolitan, earned wide credit as arbiter of what counted as authentic black expression. More to the point, Hurston knew that Van Vechten exercised sway over Hughes, mentoring him in the ways of establishing one’s literary reputation. (Van Vechten, with access to white publishers, was a gatekeeper of an expanded audience.)

Most notably, Hurston here claims that she self-censored her reaction to the way white readers and editors had praised the use of dialect and folk material, the blues and its jazz adaptions. The problems offered no unequivocal solution. She didn’t want to “cry…down” the praise of any poet for merely using black subjects and idioms. But she didn’t expect low or folk material to be simply artistic. Cullen would have sympathized. Black poets were just beginning to write about subjects, and in certain ways, that opened the “limited field,” and Cullen and Hughes, not to mention Hurston herself, continued to explore that field in different directions. But Cullen always knew — and took great delight in knowing — that wherever his explorations took him, whatever he wrote was written by a poet who happened to enjoy being a black man. There was plenty of poetry in that. •

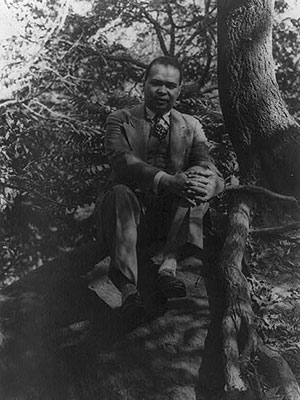

Image courtesy of Carl Van Vechten via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons)