“I have had many talented people ask me how to get into the comic book business. If they were talented enough the first answer I would give them is,‘Why would you want to get into the comic book business?’ Because even if you succeed, even if you reach what might be considered the pinnacle of success in comics, you will be less successful, less secure and less effective than if you are just an average practitioner of your art in television, radio, movies or what have you.” — Stan Lee, 1971 1

“I’ve never seen Stan Lee write anything . . . It wasn’t possible for a man like Stan Lee to come up with new things – or old things for that matter. Stan Lee wasn’t a guy that read or that told stories. Stan Lee was a guy that knew where the papers were or who was coming to visit that day.” — Jack Kirby, 1989 2

It’s a complex world out there, filled with millions of people creating millions of things and influencing our lives and culture in ways we can’t always fully grasp. But we’re a simple species, barely able to keep it together long enough to pay the bills and get the kids to soccer practice. So we create some shorthand myths and mnemonics for those aspects of our world that might not interest us much beyond acknowledging their existence. To wit: fine art means Picasso and Da Vinci. Classical music is Mozart and Beethoven. Napoleon was a short French guy in a funny hat. And Stan Lee created Marvel Comics

Except that he didn’t. At least, not entirely. But for those uninterested in the history of the American comics industry (i.e. most people), the complex debate about who exactly was responsible for the creation of the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, and whatever else is coming soon to a theater near you, probably comes off as so much nerd talk — it’s easier to just say Stan Lee did it. He was the one who kept showing up in the movies after all, displaying a loveable cornball character of his own devising.

And Lee, who passed away last month at the age of 95, was all too happy to propagate that myth, even if that meant pushing his co-creators out of the spotlight, or looking the other way when they were denied proper financial compensation.

Born Stanley Martin Lieber to Romanian-born Jewish immigrants in Manhattan, Lee was an aspiring writer who dreamed of penning the great American novel. While still a teenager, he got a job at what was then known as Timely comics, mainly because his cousin was married to the publisher, Martin Goodman (a man few people, Lee included, had any notable affection towards).

Eventually promoted to editor-in-chief, Lee (who adopted the pseudonym because he was embarrassed to be working in comic books) spent decades writing and editing mostly derivative crap, glutting (at the behest of Goodman) the market with comics that slavishly followed whatever trends were popular at the moment, be it teen comedy, westerns, romance, or horror.

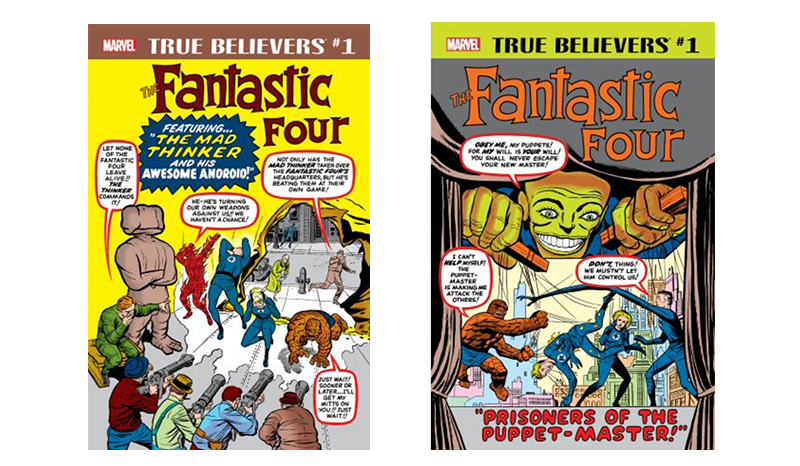

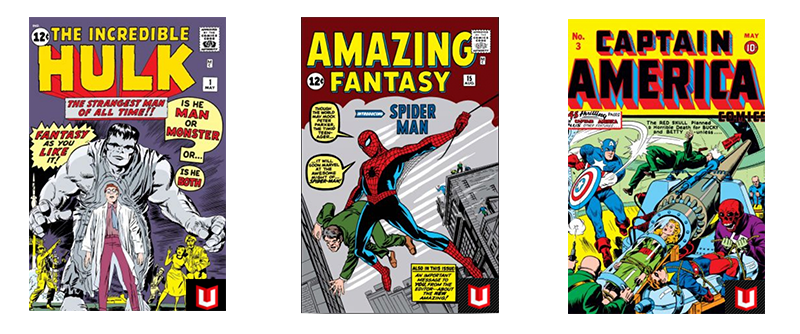

From here the story passes into legend. In 1961, pressed to come up with a new set of superheroes (DC having had success with Justice League of America), Lee (on the advice of his wife) decided to finally make a comic that he would actually enjoy reading. Collaborating with Jack Kirby (who decades earlier had made Captain America with Joe Simon), the pair created the Fantastic Four.

The FF served as a basic blueprint for what eventually became the Marvel Universe. Unlike previous straight-arrow comic book heroes, the Fantastic Four had everyday problems and recognizable flaws. They had money troubles, and could be boastful or self-pitying. They got sick. And, like a real family, they fought with each other. A lot.

Lee and company took that core formula — superheroes with “feet of clay” — and ran with it, creating the Incredible Hulk, Thor, the X-Men, Spider-Man, and so on. Key to the formula, at least initially, was layering on melodramatic aspects familiar to romance comics (a genre Kirby and Simon invented), to add a notable patina of soap-opera styled tension to the proceedings. Would Peter Parker ever get whatever girl he was mooning over? Would Donald Blake/Thor reveal his secret identity to shy nurse Jane? Could Bruce Banner ever find happiness with Betty Brant despite turning into the Hulk?

But there was perhaps no greater character at Marvel than that of “Stan Lee,” the goofy, irascible hype-man persona that Lee took on in the letters columns and even the comics themselves. Part grandiose carnival barker, part self-mocking cornball, part knowing cynic, Lee encouraged readers to feel like they were part of a special club, one that gave them a peek into the magic “Marvel Bullpen” where Lee, Kirby, Steve Ditko, and other artists buddied it up while inventing great stories for the next issue. Marvel readers were “true believers” that thrilled at the various exploits, but were smart enough not to take it too seriously. Sure, it’s just a dumb comic book, Lee seemed to proclaim in the indicia of every issue, but check out this layout — pretty cool, right? Lee made it feel like reading comic books, for perhaps the very first time in its history, was hip.

But that persona was really the only thing “Smiling Stan the Man” ever created on his own. The fun, clubhouse atmosphere 3 Lee glamorized didn’t really exist — all the artists were freelancers that worked from their respective homes. More importantly, while Lee presented himself as Marvel’s impresario and guiding force, all the characters, from the FF on down, were collaborative affairs that took equal measures, if not more, from the artists that delineated their adventures.

Part of the problem with figuring out who came up with what has in large part to do with what became known as the “Marvel Method.” As Marvel grew in popularity, Lee allegedly found it extremely difficult to find time to write. So instead he’d brainstorm a brief plot synopsis with the artist, who would then use that to break down the art, with Lee adding the dialogue once it was finished. By the end of the ’60s, however, Kirby and Dikto were coming up with the storylines on their own, with Lee offering little input until the end. This back and forth method became so hallowed that it became de rigueur at the company for several decades (though it supposedly is rarely used now).

Over the years, Kirby and Ditko, as well as others, have disputed Lee’s version of events and the amount of his contribution in general. It would be unfair to say that Lee had no hand in Marvel’s creation 4. But at the same time, all you need to do is look at what these artists did before and after their time at Marvel to understand how integral they were to the company’s success. Except for Spider-Man and Dr. Strange, Kirby had an strong hand in many of those early Marvel creations. You can draw a straight line from Kirby’s work on ’50s books like Challengers of the Unknown to The Fantastic Four (Ben Grimm resembles Kirby more than any other Marvel character resembles Stan Lee). And the epic, star-spanning dynamism he gave to titles like Thor continued apace in later works like his New Gods series. And if supposedly, Lee wanted to create a teenage hero with spider powers, it was Steve Ditko that came up with the look, made him a put-upon nerd. It was Ditko’s strange, otherworldly landscapes and characters that made Dr. Strange so fascinating, not Lee’s dialogue. Lee might have made Marvel Comics fun, but Kirby and Ditko made them exciting.

It’s to Lee’s credit that he did understand — perhaps better than any other editor working in comics at the time — the considerable talent he had. The Marvel method, though messy, gave people like Kirby a wide enough latitude to let loose their imaginations rather then simply following the publisher’s instructions. Perhaps one of the biggest shames surrounding this credit controversy is that it obscures Lee’s very real genuine contributions as an editor. In their excellent book Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, Tom Spurgeon and Jordan Raphael note:

[Lee] got the best work out of artists who had been ignored by other companies. He rooted out the essence of what was appealing to the readers, distilled it and communicated it successfully to a wide variety of artists and writers. He recruited new talent according to both short term and long term needs and assigned them to roles suited to their particular skills. He also did the best writing of his career, in service of ideas from other artists and working with artists whose creativity was subsumed into Lee’s own. No pop culture phenomenon has ever offered its readers more than Stan Lee’s Marvel gave comic-book fans.

But he was also the company man, the guy actually in the office. So that when reporters from Rolling Stone or filmmakers like Federico Fellini stopped by to find out what this Marvel Comics was all about, Lee was the person who met them at the door, excited and happy to talk about comics’ unrecognized potential, and maybe his own as well. With college lecture tours and media profiles, Lee quickly became Marvel’s biggest hype man off the page as well as on it, obscuring the work of his increasingly resentful co-creators in the process. That spotlight, combined with the uncanny way he was able to forge a relationship on the page with readers as the “with-it” uncle in comics, indelibly conjoined Marvel and Lee in a way that Kirby and others simply couldn’t.

It’s made worse by the fact that while Lee was eventually able to become a very rich man, Kirby and Ditko (and countless other artists) did not. None of them, Lee included, owned the characters they created, but while Lee’s presence was seen as integral to the enterprise, and he was able to eventually parlay it into a notable stipend, Marvel’s later owners could never fully appreciate how integral his collaborators were. In fact, when Marvel finally started handing back original artwork around 1985, the company told Kirby if he wanted his art back (or what was left of it), he would have to sign a draconian contract foregoing any claim to any of the characters he helped create. Lee should have spoken up for his former collaborator and colleague. But he didn’t.

Ultimately, the problem with Stan Lee is the problem with the comics industry itself. It was an industry created by venal, greedy people who had little regard for their workers beyond how much they could squeeze out of them. To be an artist of talent and note in comics meant at some point you were going to be treated like shit. Repeatedly. Perhaps if you were a lucky or really talented, you could get out and get a comic strip, or illustration, or even animation. But you weren’t going to find success and a sustainable career in comics.

Even Lee, who profited more than any of the other Marvel collaborators, eventually left comic books for the glamour of Hollywood. While his attempts to become a mogul, pitching endless ideas to producers, was a mixed bag at best, he was nevertheless able to see the characters he helped bring to life thrive on the silver screen and continue his role as comics’ loveable huckster uncle in an endless stream of cameo appearances. And “Stan Lee” the character thus became inseparable in most folks minds from Stanley Leiber, the editor, writer, and collaborator.

It made complete sense that he would eventually leave comics for the movies. It was where the money was. It still is. •

1. Quote taken from a speech Lee gave at the Lamb’s Club in New York, reprinted in Marvel Comics: The Untold Story by Sean Howe

2. From an interview with Gary Groth that ran in a 1990 issue of The Comics Journal magazine. Reprinted in The Comics Journal Library Vol. 1: Jack Kirby

3. Lee wasn’t the first editor to do this. Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein created a similar feel with the EC Comics line back in the 1950s.

4. In his book on Kirby, Hand of Fire, Charles Hatfield writes: “As editor and chief spokesman for Marvel, Lee’s presence was sustaining, generative and overwhelming: his verbal swagger and editorial cunning were definitive to Marvel, and documentary evidence suggests he was, early on, both Kirby’s guide and active collaborator in envisioning such properties as The Fantastic Four.”

Featured image by Isabella Akhtarshenas. All other images courtesy of Marvel.