For some of us, Fight Club is like a dirty bomb going off in the culture. I walk out of David Fincher’s iconic film sometime in the summer of 1999 feeling like I’ve just been touched by mad genius. The film is a hot, filthy, stylish channeling of rage against consumer culture and manufactured masculinity and the failing aspirations of an entire civilization. I love it. All of my male friends love it. We can’t stop talking about the one thing you’re not supposed to talk about.

Six months later, November 30, 1999, thousands of protesters are streaming into Seattle — most of them from student groups, labor organizations, and NGOs — all there to stop a big meeting of the World Trade Organization. Some of these protesters seize control of key intersections by chaining their arms together into “lockdown” formations. Others use newspaper boxes to form barricades. They stage marches and street parties designed to block traffic and prevent the WTO delegates from reaching the convention center. I am watching news footage of someone throwing what looks like a toaster oven out of the smashed window of a Starbucks, and I have an uncanny feeling of recognition.

We were supposed to kill two birds with one stone: a piece of corporate art . . . and a trendy coffee shop.

Where have I seen a franchise coffee shop trashed by anarchists before? In Fight Club, of course.

In that moment, it occurs to me that Fight Club might be a politically relevant film.

That same year, I learn what “culture jamming” means. I have a subscription to Adbusters. I laugh at fake vodka ads for “Absolut Impotence,” and I observe National Buy Nothing Day every Black Friday. “I shop, therefore I am.” I am pleased with the thought that if I put that on a bumper sticker, many people will miss the irony. (Oh, I get it. It’s very clever . . . how’s that working out for you?). Of course, I am a deeply embedded in the bourgeoisie, so I can only dream about scaling a billboard with a backpack full of spray paint cans.

After Seattle, I start seeing Project Mayhem everywhere.

A few months later, I am in Washington D.C. for a big demonstration against the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Again, I see Project Mayhem, organized and serious and walking around in broad daylight calling themselves the “Revolutionary Anti-Capitalist Block.” They are mixing in with the crowds, wearing black sweatshirts with black or red bandannas pulled up over the lower halfs of their faces, some with gas masks slung around their necks or strapped to their backpacks. They move through the sluggish crowd in agitated packs of five or six, half running, shouting slogans. Some are carrying cans of red spray paint. They paint “Fuck the Whorehouse” on one of the White House outbuildings and a red anarchy symbol on the door of the World Bank. They drag garbage cans or parking signs into the street as they march.

On September 11, 2001, I am watching the endless replay loop of the Twin Towers falling, and I’m thinking about the final scene in Fight Club, where the Narrator kills Tyler Durden, but civilization is about to end anyway because Tyler’s soldiers have wired up explosives into the buildings that house credit card data for millions of Americans.

Trust me. Everything is going to be fine.

By this time in my life, I’ve seen maybe a dozen videos of big building demolitions on TV — hotels, factories, housing projects — but only one with a soundtrack, and that is at the end of Fight Club. It is the Pixies’ “Where Is My Mind,” a song that was inspired by a small fish chasing after lead singer Charles Thompson while he was snorkeling in the Caribbean.

This is it. The beginning. Ground Zero.

Two years later, in January of 2003, I take a bus chartered by a Presbyterian church in Princeton, New Jersey, with ordinary people who look like they are dressed for a baseball game or a day in Atlantic City, carrying backpacks with water bottles and sunscreen and sandwiches made earlier that morning on someone’s granite countertop in Somerville, Mendham, or Princeton. We’re on our way to stop a war before it starts, this little army of progressives, church-going liberals, libertarians, socialists, conscientious objectors, skeptics, pacifists, conspiracy nuts, contrarians, Pax Christi-ites, do-gooders, soft touches, and history teachers for peace, arm-in-arm with the far-left carnival with its two-story-high puppets and 20-foot-wide banners and impromptu walking drum circles. We flood Washington D.C.’s Ellipse in a sea of baseball caps, sweatshirts, and “No Blood for Oil” signs.

Project Mayhem is there too, flowing around the edges of the crowd in small platoons, indissoluble and aching for a dust-up with the police, a breathless pack of young men, all lean, in their late teens and early 20s, wearing black clothes with black boots and black backpacks and red bandanas pulled up over their noses.

You have two black shirts? Two pairs of black trousers? One pair of boots? Two pairs of black socks? One black coat? Three hundred dollars personal burial money?

The war comes anyway, and then Katrina, and by 2005, I am living in another country. The lid has blown off. The government is faltering, and everywhere you can smell failure — in Congress, in the bureaucracy, in the way people talk, as if there are enemies in our midst. There are a lot more people talking about their pathologies, their medications, their conditions. It’s becoming a nation of invalids. Obesity and diabetes are on the rise. Heroin and opioid abuse and mass shootings are becoming epidemic.

I’d be very careful who I talked to about this. It sounds like someone dangerous wrote it . . . someone who might snap at any moment, stalking from office to office with an Armalite AR-10 Carbine-gas semiautomatic, bitterly pumping round after round into colleagues and co-workers.

Then the economy crashes — the Great Recession — and a few years later, the first big revolts against the system — the Tea Party, and then Occupy Wall Street.

Project Mayhem is back again, but this time, they’re unmasked, leading teach-ins in Zuccotti Park and organizing an ad hoc government. I’m on a learning curve. I despise politics, ever since I watched that clip of Ralph Nader being denied access to the 2000 presidential debates by a big, scary state trooper. But there is a new politics opening up; I can feel it. It doesn’t have a name yet, so I’m going off-script for answers.

I’m reading Emma Goldman.

“If voting changed anything, they’d make it illegal.”

I’m learning about anarchism, teaching myself. I’m reading Bakunin and Kropotkin and Edward Abbey and Abbie Hoffman. I’m discovering the alternate history of America.

I’m learning about the black bloc. This is the anarchist tactic of wearing black and concealing one’s face to avoid identification and to operate a single, unified group: anonymous, powerful.

In Project Mayhem, we have no names.

•

In February 2012, the Occupy movement is spreading around the country, and I finally get around to reading Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 novel Fight Club. Much of the plot is recognizable from the film; the Narrator — a timid, repressed young man — suffers from a psychological break in which he unconsciously creates a new persona named Tyler Durden. Tyler is Pan-like, charismatic, unrestrained. He is like the ancient Greek Cynics, who lived “like dogs,” fornicating in public and flouting every rule and convention — the embodiment of the id. Together, the Narrator and his doppelganger create Fight Club, a secretive organization that allows men to achieve catharsis by pummeling one another in the basement of a dive bar.

Fight Club expands and proliferates, and eventually enters a new stage: “Project Mayhem” — an organized campaign to assault the symbols of consumer capitalism, culture jamming on a large scale. Unlike the film, the novel provides an origin story for Project Mayhem. The idea is born one morning over breakfast, as the Narrator and Tyler fantasize about taking their project to the next level. They want to blast the world free of history, paint skyscrapers with totem faces, dig clams next to the skeleton of the Space Needle. They dream of an anarcho-primitivist post-apocalypse — the world according the Unabomber’s manifesto — full of wild men living as nature intended, free of the constraints of civilization and the influence of technology.

Tyler is content to tear civilization down, but the Narrator needs to rationalize their revolution. He speculates that Project Mayhem will save the world by giving the Earth a “remission” from human activity — long enough for it to recover.

Tyler mocks him:

“You justify anarchy . . . You figure it out.”

The group evolves once more, this time into a terrorist organization dedicated, as Tyler says, to “the complete and right-away destruction of civilization.”

Fincher’s Fight Club ends with Tyler’s goal of destroying civilization about to be realized. The financial system is literally collapsing, one building after the next, and with it, presumably, civilization itself. The audience is invited to imagine a world wiped free of debt like a modern iteration of the Biblical Jubilee year.

Out these windows, we will view the collapse of financial history. One step closer to economic equilibrium.

In the novel’s finale, however, Tyler has planted explosives in a 191-story skyscraper — a towering symbol of capitalism — in order to collapse it onto a nearby national museum. The Narrator shoots Tyler and the terrorist plot is foiled. The Narrator ends up in an asylum. There, he imagines he is in Heaven and that the head psychologist is God. But Project Mayhem is still with him:

Because every once in awhile, somebody brings me my lunch tray and my meds and

he has a black eye or his forehead is swollen with stitches, and he says:“We miss you, Mr. Durden.”

Or somebody with a broken nose pushes a mop past me and whispers:

“Everything’s going according to plan.”

Whispers:

“We’re going to break up civilization so we can make something better out of the

world.”

I prefer this ending because it more adequately expresses the essential conflict at the heart of our civilization. We are stuck in a comfortable asylum, fantasizing about the end of the world.

•

After Occupy, the news is filled with images of anti-state street protests in Cairo, Ankara, Tehran, and São Paulo. We live in the Project Mayhem Age now, in thrall to the politics of the anti-state — terrorists and anarchists, survivalists and militias, neo-Nazis and the Klan versus Antifa in a battle royale for the streets of Charlottesville while the police stand by, helpless to stop it. All over the world, the figure of the masked, black-clad young man is now the icon of resistance.

Jump ahead to 2016. I’m watching Donald Trump channel rage into political action like no other politician I’ve seen in my lifetime. And again, I have this uncanny feeling. I can’t stop thinking about Tyler Durden’s description of an entire generation of forgotten men as the “crap and slaves of history” and the “middle children of history, raised by television to believe someday we’ll be millionaires and movie stars and rock stars, but we won’t.”

Who would America’s middle children of history vote for — if they were inclined to vote at all, if you made them choose — between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton?

We have no great war, or great depression. The great war is a spiritual war. The great depression is our lives.

I see a bit of Tyler Durden in Donald Trump’s appeal — in the electoral “fuck you” that was aimed like a Scud missile at the experts, the bankers, the financiers, the tech billionaires, the pharmaceutical moguls, the pundits, the Ph.D.s, the Bushes, McCains, Romneys, and Clintons and every other slick riding in the engineer’s cabin of the slow-motion trainwreck that is modern America.

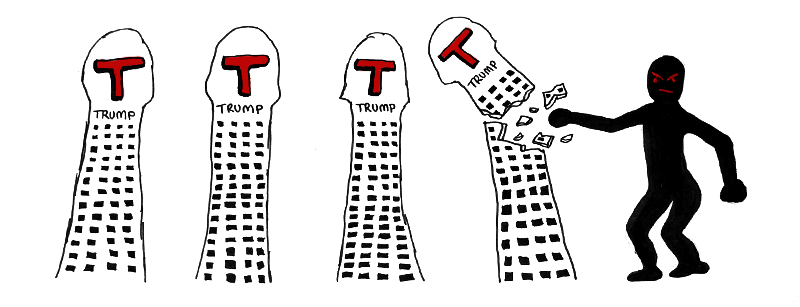

Wait a minute. Donald Trump is nothing like Tyler Durden. Trump is a modern-day robber baron — unprincipled, greedy, self-aggrandizing media whore — a man rooted tooth-and-nail in the viscera of consumer capitalism, seeking to master it like a scary wizard-master of the universe. He builds phallic towers of glass and steel and puts his name on them. Tyler, on the other hand, is the perfectly formed archetype of rebellion — lean, young, articulate, and bent on bringing down the system. He hates capitalism; in fact, he wants to destroy it and then live a hunter-gatherer’s fantasy life in the ruins. Tyler tears down the phallic towers.

But then I remember the birth of Project Mayhem.

“You justify anarchy . . . you figure it out.”

Tyler Durden has no desire to “figure it out.” There is no reformation coming after Project Mayhem. Tyler has no ideology, no big ideas for transforming society. He is the projection of the civilized man’s deeply repressed desire to tear it all down.

Self-improvement is masturbation. Self-destruction is the answer.

If we stop searching for the “real Trump” under the tidal wave of ungrammatical tweets and absurd, puerile theatrics — if we stop trying to make his crooked lines straight with gigabytes of punditry and serious political commentary — Trump oddly begins to come into focus. The Trump who is both adored and reviled is, like Tyler Durden, an agent of chaos. He is a destroyer, summoned up from a tornado of rage and shattered dreams by some kind of dark magic, and then loosed upon the Earth.

Fight Club should have prepared us for our current political reality, in which rage pushes and pulls at the levers of our society, seemingly without logic or agency, a dark force of nature that can neither be predicted nor contained. This energy is a byproduct of consumer capitalism, which promises a level of material wealth and happiness that it cannot deliver. The result is a quiet army of disenfranchised anti-progressives, on the Left and on the Right, who have lost faith in the fundamental American myths of self-improvement, self-reliance, and self-control. Some are angry at the system because it can’t deliver on its promises; some have always believed the system was broken and want to tear it down to build a new world.

Some of these people fantasize about peeing in the crème anglaise and vandalizing billboards and smashing the window of a Starbucks. Some are buying guns and stocking their houses with a ten-year supply of canned goods. Still others are channeling their anger into the ballot box, voting to overturn the established order.

Tyler Durden is a metaphor for the dark inexplicable in American politics — the American id, that metastasized bundle of fear and desire that is the true driver of our politics. He is what we see if we are willing to gaze past the safe, ordered assumptions of partisan politics and into the abyss that lies on the other side. In this void, reason-driven cause-and-effect breaks down and the familiar light of binary political discourse flickers out completely. In this dark, ever-widening space between our inflated American dreams and the grim realities of consumer capitalism, monsters are born. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.