Tuesday, March 24, 1998: I am at work, sitting in front of an electrical grid map and dispatching instructions over the radio to a powerline repair crew. My job is to safely isolate a section of cables they will repair. The door to the control room cracks open, my co-worker leans inside. She looks frightened. Her voice trembles as she says the unthinkable.

“Danny. There’s been a shooting at Westside.”

Ashley, Adam. My children’s names rush to my mind.

Ashley attends the seventh grade at Westside Consolidated School District, and Adam is in the second grade. The school serves the small Arkansas towns of Cash, Egypt, and Bono where my home on Main Street is located. I live in white, rural America, the safest neighborhood in the world.

My brain processes the horrific phrase, a shooting at Westside, and sends my hand to grab a nearby phone. I watch, as if from a distance, fingers punching the buttons that will connect me to my home. On my second try the phone begins to ring. The rest of me is in limbo. Another company engineer takes over my work.

Twenty-five years later now, I’m still not certain of the entirety of my thoughts as I sat there obsessed with the phone’s interminable ringing, as I desperately waited to connect with my family. I think at some point I considered that I’d sent my daughter to her death. On Monday, the day before the shooting at Westside, Ashley and Adam stayed home to complete a sample homeschool lesson plan. We wanted to evaluate the process for our family. The next morning, as I left for work, Ashley complained about not feeling well. I insisted she go to school because of having missed the day before.

“Dad knows best,” I’d said.

I see myself that day, March 24, Tuesday, clinging to the phone at my ear, my surroundings fading as my thoughts turned inward. A shooting. Not where I lived. I started praying silently, unaware that in this ancient time before smart phones and the instant connection to the internet, ambulances were already pulling into the local hospital with wounded children. One of the first responders, a veteran, would later remark that the scene at Westside looked like a warzone.

I only know from the movies what that looks like.

A couple of years after high school, I joined the Air Force in 1974, served four years, and then used the G.I. Bill to help pay for college. After graduating from the University of Arkansas in 1986 with degrees in land surveying and civil engineering, I received a commission in the Air National Guard, later serving in the Air Force Reserve, and retiring as an O6. I’m a Vietnam Era veteran, but not a Vietnam vet, sent to Germany in 1976 to support the Cold War against the former U.S.S.R. Activated after 9/11, instead of being mobilized to the desert, I was ordered to Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida, tasked to use my engineering skills to build up and adapt First Air Force (1AF) facilities for their increased mission to defend the skies inside our borders against terrorists.

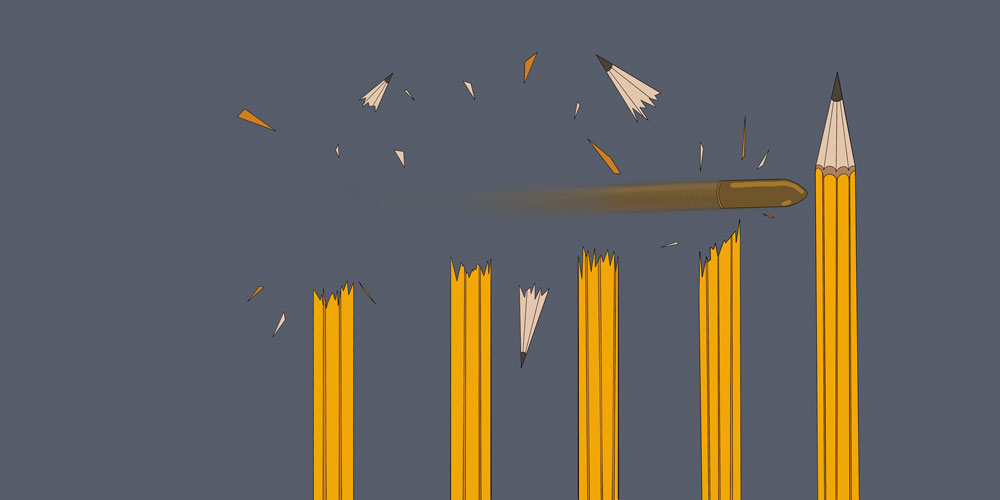

Terror is a child with a gun.

On Monday, March 23, 1998, the day my family is practicing homeschool, Westside students Andrew Golden (age 11) and Mitchell Johnson (age 13) steal nine guns and 2,000 rounds of ammunition from Andrew Golden’s grandfather. The two boys load Johnson’s stepfather’s van with the guns and ammo. They pack camping gear and other items for their getaway. On Tuesday, the two boys drive the van down a remote two-lane highway that curves through the pastoral countryside to their school. They take a side road and park next to a field across from the Westside Middle School playground. After lunch, while students are in their fifth-period classes, Golden enters the school through an exit door. He activates a fire alarm and then runs to join Johnson, who waits with their guns in the adjacent field. From behind a fence about 100 yards from the exit door, as 87 students and nine teachers evacuate the building, the two boys begin firing at them with handguns and semi-automatic and bolt action rifles, a total of 30 rounds.

Before I was 29 years old, I had a gun pointed in my face three times.

I’m 19 the first time, at Little Rock for the Air Force physical exam. That night an argument begins over a girl I’d just met. A 38 Special appears — silver barrel — stranger holding the gun. The second time, I’m out of the Air Force, back in my hometown, attending school at the local college. One night while sitting at the end of the dining room table in my brother’s house with him and his friend, talking and having a beer, when an acquaintance of the friend comes over unannounced. The young man sits facing me and lays a huge long-barreled magnum pistol on top of the dining room table. His hand rests on the grip. The barrel pointed at my chest. Found out later that this person was a rival drug dealer of my brother’s friend. The third incident involved road rage, while I towed a trailer of household goods along the winding two-lane highway to Fayetteville, AK after being married in Walnut Ridge that weekend. When I pulled to the side of the road, the driver of the offending/offended vehicle walked toward me with his arm at his side, a small pistol gripped in his hand pointing to the ground. My Grandmother Bratcher would say in these instances my guardian angel had her arms wrapped around me, protecting me from harm.

Where are the kids?

This is the prayer-laden question fighting to leap from my mouth as I gripped the phone.

The mother of my children finally answers.

“They’re here.”

She’d decided to let Ashley and Adam stay home for the day.

I cannot imagine the heartbreak of other Westside parents when they learned of the worst.

That evening, the news reported on the carnage at Westside: One teacher, Shannon Wright, and four students mercilessly gunned down: Natalie Brooks (age 11), Paige Ann Herring (age 12), Brittheny Varner-Wilson (age 11), and Stephanie Johnson (age 12) who Ashley usually sat next to in her fifth-period class. Another teacher and nine other students wounded, among them girls I had coached on the softball team when they were still in elementary school.

The Sunday after the tragedy, I drove the long mile to our little church in Bono. Horribly surreal in so many unfathomable ways, dozens of vans with antennas and satellite dishes lined up and down the street to the church, many parked in front of the old school gym where I had once organized and managed a youth basketball league. As my family and I left our car and started to walk to the church, I was approached by a man who said he was from the BBC. He kindly asked if I’d like to say something.

I shook my head. No.

Even now, 25 years later, I struggle with what I could/should say that is respectful to the survivors and their families, and of the dead. Of the millions of words in the English language, no order of syntax, choice of style, and persuasive tone can change the past, but I hope perhaps a few nouns and verbs and complements placed well can open people’s minds to take action. I believe only God knows his plans for each of us, but it’s clear to me that he expects us to do more than pray for the souls of murdered children and send good thoughts to their grieving families. America has a problem. And from my experience as a professional problem-solver, the first step in addressing a problem is answering this question:

What exactly is the problem?

I’ve been told that the way to know if you have a drinking problem is if you have problems when you drink. Alcoholism affects everyone, from kings to paupers, and Liberals love their hooch as much as Conservatives love their guns. Yet Republicans and Democrats have worked together to regulate driving while under the influence of alcohol, and statistics show DUI deaths have drastically reduced as laws have toughened. Gun laws have been passed to prevent bad people from getting guns, but statistics conflict regarding the effectiveness of these laws. During the Vietnam War, the evening news posted a tally of the wounded and killed in action during a given week. The ratio of dead Communists to Americans was always much higher. We were winning, it seemed. Statistics are sometimes the product of opinions, and in a free country everyone is entitled to their own. Yet a dilemma manifests when people’s ideas are lumped together, and we are sorted by politics to one side of an issue or the other, which results in deadlock. The corporeal truth is that opinions can’t fix problems, and neither do people who ignore them.

If our country has a problem with guns, does it have a gun problem?

Guns are a big part of Arkansas’s culture, as they are in other states and communities. I fondly remember as a young boy finding a 16-gauge shotgun and box of shells under the Christmas tree. My mother’s Blue Ribbon recipe for fried squirrel was legendary. Weapons equate to rural life other than just hunting. My daughter Ashley’s grandmother, Mir, was part Native American, of Appalachian heritage, was kind, gentle, highly intelligent, an avid hunter, and one not to be messed with. One day Mir ran a band of poachers off her homestead in the thick pine forests near Texarkana, TX. The men, possibly lacking fully functioning brains, hightailed it to the sheriff to complain that a crazy woman had threatened them with her shotgun. Next day’s headline in the paper: Granny’s Got a Gun. I don’t know if Mir would’ve actually shot the trespassers, but woe the fool who dared threaten her family, especially her grandchildren.

Isn’t the perceived need for increased personal protection the reason in many American homes there’s now a handgun next to the holy book on the nightstand? But do more guns make America safer or less safe?

Exactly 20 years after the Westside School shooting, on March 24, 2018, I traveled from Okinawa, Japan to Washington D.C. to participate in the March for Our Lives protest. 800,000 people! I felt like a bean in a jar full of beans, and the closer I moved to the bottom of the jar the more I felt the weight of the other beans. My friends and I walked down Pennsylvania Avenue with thousands of other pilgrims to Third Street where a giant stage had been erected. My best view came from holding my camera high above my head and looking at the pictures it recorded. But, I didn’t have to see them. Over the loudspeakers, I heard the student leaders from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL, who, after the shooting at their school, catalyzed the march. Their voices quivered as they remembered fallen classmates, as they talked of lives cut suddenly and violently short, of the small talk and the kidding around they’d never do again with their friends, of hopes and dreams that would never be realized.

Most importantly, these magnificent young people manifested a vision of the future, simple but succinct: Never Again. Enough. More so, they acted on their vision with a plan of action. They pleaded with us to let our senators and our congressmen and congresswomen know they will be held accountable for their actions and inactions that contradict measures to prevent another school shooting.

And yet school shootings are still happening. Our “Do Nothing” solution hasn’t worked. One day, as I drafted my thoughts, the country reeled from another shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. Fourteen children and one teacher murdered. And now, as I write, America is suffering the aftermath of another shooting and mourning the loss of innocent children and adults murdered at The Covenant School in Nashville, Tennessee. Before this article is published, there will likely be more occurrences.

Why?

Foremost because we are debating symptoms and solutions without still knowing what the problem is. Many of the 800,000 people who attended the March for Our Lives sent messages to their elected officials, and many of them likely suggested better control of guns, but a balanced slug of other people (factoring in the per capita equivalent of Pro-Gun Lobbyists) sent messages to their elected officials in a counter-response, in effect neutralizing both sides.

Everyone acted within their First Amendment right to free speech. The weapons used by the gunmen who killed the children at Westside Middle School, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, Robb Elementary School, and The Covenant School were bought legally. The gun owners, whose weapons were used in the massacre of children, exercised their Second Amendment right to bear arms. I believe all sides, Democrat, Republican, and Independents, equally grieve these tragedies. However, from my experience, to solve any problem, some change from the status quo is necessary.

And so, the root of the problem lies in our past.

The fundamental Rights on which the United States was founded concern Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. Our founding fathers knew that an ever-changing people required an adaptable government to maintain these unalienable Rights. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “…whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” Just recently, after 911, our government instituted and organized its powers in the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, its purpose to effect our Safety.

The problem is that Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness are in conflict.

Children don’t deserve to be gunned down at school or at home or anywhere else.

People have a right to own guns.

How can we foster Life to children and still allow Liberty to gun owners? Where in between is the medium of Happiness?

Some argue that America should emulate what works in other countries. I could write pages of reasons why I think that won’t work, but the basic tenet is that there is no other country in the world like ours. We need an American solution to an American problem.

That means “We the people” have to fix it.

As a government of the people for the people, we need to modify our contract with each other. People still need to be respected as individuals. Individuality is a hallmark of America’s creativity and ingenuity. However, an individual’s liberty should not interfere with the public welfare. America’s strength is its diversity, but one group’s culture should not diminish the well-being of the Union’s culture. Indeed, our constitution is the framework that unites all Americans. It is our common culture. And it must be revised to correct America’s burgeoning culture of gun violence.

What do we need to fix?

In general, gun proliferation in America is a result of Fear, which stems from a proportionate rise in the number of residents who, justified or not, sense insecurity and instability in their lives. And I think everyone would agree that if the authorities had had an inkling of what 13-year-old Mitchell Johnson and 11-year-old Andrew Golden planned to do on Tuesday, March 24, 1998, they would have done everything in their power to prevent the tragedy.

Prevention is key.

While serving in the Arkansas Air National Guard, I once held the office of Chief of Readiness. The three stages of readiness for a disaster are Prevention, Preparedness, and Recovery. For an event like a chemical or biological or nuclear weapon attack, no matter how well a force prepares, the destruction and death and injury can be beyond massive, and even beyond reckoning. That’s why our government continues to work with other nations to reduce the development and manufacture of these types of weapons. Preparedness incorporates training, responsibility, and accountability — these elements should apply to the ownership of guns as well. Ask the parents, there is no recovery from the loss of a child.

Prevention measures must be adequate. To paraphrase a line from the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous, “How It Works,” half measures will avail us naught. Putting police in schools and arming teachers is a preventative measure, but it is a last resort, and about as effective as crossing one’s fingers and hoping for the best. Would it not be better for a tax-paying society to spend funds to intervene in two boys’ lives so that a tragedy such as “Westside” is diverted at the cognitive stage, that is, even before the thought of such a thing manifests? But how though can society intervene when mental illness continues to be stigmatized? Why would a parent or guardian call attention to their child only for them to be set apart and ridiculed and bullied and subjected to discrimination? Instead of receiving proper care, some children are saddled with the labels of Troublemaker, Misfit, Loser, Loner — Killer.

We have no excuse. We, as a society, have failed to properly address mental illness, guns, and their dangerous linkage to gun violence. But We have also ignored other issues that are deteriorating America’s social fabric and feeding the fears of its citizens. The greatest threat to our national security has become ourselves.

We the People must change.

I’m certain an “Article V Convention” would likely produce more opportunities for extremists’ political theater and self-promotion than positive changes. And during the debate of a joint resolution to amend the United States Constitution two competing visions will fight to decide America’s future. One vision is an isolated and selfish country where every home, school, workplace, place of worship, shopping center, theater, stadium, government and private institution is fortified with guns. The other vision is a safe and stable America where the Happiness of one citizen does not deny the fundamental rights of Life and Liberty of another citizen. One vision will pass a legacy of violence on to our children, and the other will lend them a beacon to light their path.

Fear or Hope?

Which will we choose, America?•