In his book Varieties of Religious Experience, William James wrote about the power the irrational holds over the rational:

If you have intuitions at all, they come from a deeper level of your nature than the loquacious level which rationalism inhabits. Your whole subconscious life, your impulses, your faiths, your needs, your divinations, have prepared the premises, of which your consciousness now feels the weight of the result; and something in you absolutely knows that that result must be truer than any logic-chopping rationalistic talk, however clever, that may contradict it.

So what do you do as a rational, intellectual person who is fighting a group that is in the grips of their intuition? How do you combat the power that holds? It doesn’t make sense to right the irrational with the rational. You can explain to, say, a Trump supporter very coolly that his economic policy would have disastrous ramifications, or that his foreign policy approach could very well lead us into decades of conflict, but if he’s caught up in a nationalistic fever, especially one that is being used to shore up a fractured sense of self, you will only antagonize and never sway.

Shlomo Sand, an Israeli historian and writer, sees his own nation in the grips of a powerful myth, the myth of the Jewish State. And he sees how that myth invigorates the right wing and radicalizes its Orthodox youth. And he sees the myth in the foundations of a government that indicates on every citizen’s identification card whether its holder is Jewish or Arab. So what does he do? Does he coolly explain the disproportionate response the Israeli military has to Palestinian protesters? Does he campaign for a slightly more moderate politician? No. He goes after the myth.

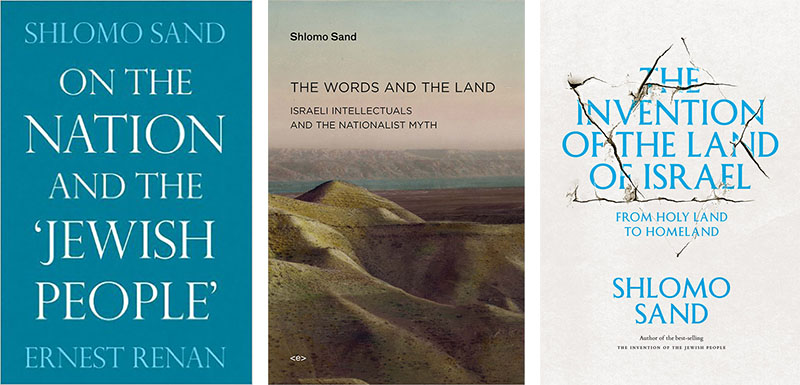

Which is what he has been doing in books, like How I Stopped Being a Jew, The Invention of the Jewish People, and The Invention of the Land of Israel. For Sand, the myth of the Jewish State has its roots in an incorrect idea about a Jewish culture. There is, he says, no such thing as a secular Jewish culture. Judaism is a religion, and that is it. The very idea of the Jewish people as an identifiable ethnicity, separate from religious affiliation, comes from their historical enemies, from the Inquisition in Spain, to the Russian pogroms, to Nazi Germany. Once you renounce the religion, to convert or to become a nonbeliever, you are no longer a Jew. Having renounced the religion, Shlomo Sand declares himself no longer a Jew, but his writings on this topic have sparked outrage.

This Jewish identity and sense of belonging may have provided comfort during difficult times, but it also led directly to the current occupation of and civil rights crisis in Palestine. If a people believes themselves distinct and separate, it puts a barrier between them and any other group. The other becomes a direct threat, not only to their state or government but to their very existence. And so to break the apartheid state, and the normalization of living in a country that is engaged in an occupation, you have to break the myth underlying it.

Sand’s work has been incredibly controversial, both here in the States and in his home of Israel. (I mentioned I spoke with Sand to a Jewish-American publisher, and the first words out of her mouth, almost like a reflex, were “self-hating Jew.”) He is routinely denounced by critics and peers, his books in both American and Israeli press are ruthlessly reviewed, and yet his books are bestsellers in Israel and have been translated into many languages. He has earned the respect of British historian Simon Schama and the much missed Tony Judt, even while earning the ire of entire publications, like the Tablet and the Foreword.

I spoke with Sand over Skype after a trip I made to the Jerusalem Writers Festival as a member of the press about how to fight a demagogue, the international response to Israel’s occupation including the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement, identity politics, and whether it is the obligation of the Jewish people to forget about the Shoah.

JC: There is much debate in the United States over the BDS movement, about whether it is helpful to the situation in Israel and Palestine. People, in particular, criticize the academic boycott (professors refusing to speak or teach at Israeli universities), saying that shutting out voices is counter-productive. Where do you come down on the cultural and academic involvement with the BDS movement?

SS: For a long time, I was against the BDS. Historically, I knew that nobody was thinking to boycott the United States during the Vietnam War, no one thought to boycott France during the Algerian War, and so I asked myself, why is Israel the exception? Then, in the last year, the difference is — it’s too long, 50 years of occupation. It’s not a war like the Vietnam War. It’s too long, this power relationship, and if there is no pressure from the outside, I don’t believe Israel will stop the occupation. We have to understand that the difference between the United States, France, and Israel is that Israel is very dependent from a military point of view, and also from an economic point of view, especially on the United States.

Had I lost hope of any institutional change from the inside . . . Nobody here will stop Israel from continuing the occupation for 100 years more. A dangerous situation exists now. I think that the only hope to save Israel from itself is pressure from outside. From a deeply pessimistic point of view, I am thinking that any pressure on Israel is legitimate, with one condition. That any members of the BDS or other sanctions or boycott will insist that it is not to destroy the state of Israel but to stop the occupation. For example, today I cannot fight against the BDS, and I am not fighting, even if I am thinking it cannot start on the cultural and academic level. It has to be much more serious. If Europe decided to boycott Russia because of Crimea, there is not any reason European states and the United States cannot start to put pressure on Israel. Or even sanctions.

I am not for the academic sanctions because I am an academic in Israel. But I am not against it. With that one condition, I think the pressure today is not a danger to the existence of the Israeli state. We don’t really have military enemies today. It’s not the situation of the ’60s or ’70s today. This is the reason why, with a clear mind, I think the world has to put boycotts and sanctions against Israel.

JC: Your mind changed a year ago?

SS: I lost hope. After the last election, I understood something that for a long time I didn’t want to. And that is there are no socio-political reasons, any possibility that something will change from the inside. I don’t believe in the one-state solution; I don’t believe it, not because I am against it, but you cannot offer this to the most racist state in the Western world, Israel, to become a minority in its own state in a few years. It’s not a political solution. I am for the two-state solution. To arrive at the position of the two states, by the way, not a Jewish and an Arab state, an Israeli and a Palestinian state. I am not for a Jewish state, I am for an Israeli state.

JC: There was a debate some of us were having at the Jerusalem Writers Festival about whether it was possible to be just a writer in Israel, or, rather if being a writer in Israel necessitated a political awareness that came through in the writing.

SS: You visited Jerusalem, yes?

JC: Yes.

SS: When you arrived in Jerusalem, I hope you knew you were coming to the capital of a state where one-third of the citizens have no civic rights. The fact that writers like David Grossman are living in a city where one-third of the population has no civic and political rights, it’s unacceptable for me. If he’s not putting the question that he’s living in a city where a big part of it has no political, democratic rights, and he continues not to be occupied with this question, morally this is unacceptable to me.

I know I am living not far from poor people, not far from people who suffer, but living in a city where one-third of the people for 50 years have no political rights and not express any opinion about it . . . As a dissident of Jews — I am not a Jew but I am a dissident, my parents are Jews — I cannot accept it.

You can ask me: How do you continue to live in Israel? That, too, is not easy. I am very, very Israeli, most of my life I was living here in Tel Aviv, and it would be difficult for me to leave. I have hope that something will change, but to live here and not express a moral position or a political position about it is unacceptable. Even for a poet that is writing about love.

JC: How do you see the Israeli literary scene? Israel has a lot of political writers, but it also has a lot of writers who do not engage. Do you think the writers need to be more engaged philosophically or politically than they are?

SS: Much more. Most of the writers have more or less a liberal opinion. But most of the writers are not deeply engaged in anything. Part of them lost hope. Other part is very normal. Normal, you know. Normal, I cannot understand it. Especially in Jerusalem. Writers, intellectuals, are coming to Jerusalem without expressing an opinion about the fact that one-third of the population . . . I’m speaking of the people who have residency; I’m not speaking of the occupied territories. Don’t express any political engagement. I don’t want to be in a dialogue with them.

If you come to Jerusalem, it’s okay. I’m not asking you to boycott. I’m asking you to come and express your point of view. And if they do not give you the chance to express this point of view, don’t come. I am thinking that if you decided not to boycott and to come here, then you do not have the right to be silent. It’s not possible. We are living in the beginning of the 21st century in the Western world; you can imagine that Washington doesn’t give a third of the population the right to vote, the right to be a full citizen in the capital of the state? How come? Because Israel is a Jewish state, it’s not an Israeli state. This state belongs much more to someone in America who is Jewish than to student of mine, who is Arab-Israeli. I become very tired with politics in Israel. I had a chance to leave, but I hate and I love this place too much, and I’ve become too old to move.

JC: I was talking to a writer about this when I was in Jerusalem, the question of whether it is moral to continue to live in Israel. Her thought was that if the moderates leave, then it leaves the state to the fanatics. Do you agree?

SS: No. I don’t accept neutrality. The question is, what do you mean by moderate? There is no change that the moderate can do to change the situation, to prevent the catastrophe. Unfortunately, it will be after the catastrophe that we need the moderate. I am afraid there is no real future here. It’s only the last two years I started to think that from a historical point of view, this will end badly. After the catastrophe, maybe we will have the chance to make different things here.

I don’t ask a lot from people; I don’t want them to sacrifice themselves. Most of my students are living in exile now, from Toronto to Berlin. The masses in Israel, the people that vote, have not any reason to change this politics. My position about the boycott is if Israel will not have a plasma television larger than 24 inches, because of the boycott, if they’ll need a visa to travel to Europe — because when I’m talking about a boycott, I don’t mean just food. I think Israel is a very materialistic, hedonistic society. You were here, you saw it with your eyes: It’s very hedonistic. The only reason to push Israel to compromise with the Palestinians, with two states and a border from 1967, with Jerusalem as the capital of two states, the only reason to do it is materialistic pressure on Israeli society. I believe the materialistic part of Israeli culture is stronger than the myth of who we are as a people.

We are the product of a kind of colonization that started about 100 years ago and didn’t stop until now. It’s not a question of justifying this colonization or not justifying it: I justify the existence of Israeli state while knowing it is the product of a colonial state, like the United States, like Australia. I always, speaking with the Palestinians, say that the child that is the product of a rape has the right to live. With one condition: that he will not become a new rapist.

Visiting Jerusalem and the Festival of Writers is very nice. It disgusts me. It disgusts me deeply. It’s like visiting South Africa in the time of apartheid. In Jerusalem, in the occupied territories. It’s a clear apartheid.

JC: There was a talk by David Grossman at the Festival, that defended a secular Jewish identity. He’s an atheist but still identifies as Jewish. This is an idea you have taken apart in your book. What was the Israeli literary reaction to your books, given that at least for the writers who are most visible in America, like Grossman, defend the idea of secular Judaism?

SS: I am going to write something about this, about the politics of identities. It’s not only the Jewish, it’s also the Muslims. Empty identities. The Jewish identity is a religious identity with a religious culture. Zionism is a kind of zombie. The Zionist is a zombie. They define themselves as secular Jews, but they have no criteria to define what is a secular Jew. Secular Jewish identity exists because there are people who say they are Jewish and they are secular. OK. In the ’30s, a lot of Germans defined themselves as Aryans; it was, if you want, an Aryan identity. But not an Aryan culture.

What is the problem with Zionism in people like David Grossman? One of the deep weaknesses of the Zionist secular left is the fact that they don’t have anything to define a secular Jew. Memory is not enough for identity. Besides memory, you need a real culture to continue some real collective identity. To make it clear, Zionism creates here a real Israeli culture. Jessa cannot speak with me in Hebrew, she can enjoy an Israeli joke, she cannot see Israeli theater, she can read David Grossman only in translation. Me and Grossman have one thing in common that Jessa is not a part of. We have an Israeli culture. From language to cinema. You cannot explain to me what is a secular Jewish culture. For a secular Jewish culture, they need Jewish folklore, Pesach and Purim is religious. But you don’t have a lively secular Jewish culture.

The question is, for me, and I’m asking American, French people who identify as Jews: What part of your culture will you pass on to your children? Which secular culture can you pass to your children? You cut your penis to be a Jew? That’s so primitive to me. You’re going some once a year to a synagogue, you use all the ancient religious things to pretend to be a Jew, but you don’t have a secular culture that is specific for Jews. You have two things to be a Jew in the United States today: to imitate the religious people, even if you are secular; folkloric, a little bit and memory of the Shoah. It’s tragic that a memory of a tragedy defines your existence, your children’s existence. It’s very perverted to me. To insist to be a secular Jew, this David Grossman, makes him so weak in the face of Netanyahu. He’s not a Jew! We are weak here, the secular artists, because from the beginning, we were zombies. The history, the pogroms, and the Shoah made us zombies. Collective identity needs a basic culture, a daily culture, and a high culture. We created it in Israel, and so David Grossman is an Israeli writer, not a Jewish writer.

JC: What does using the memory of trauma as a collective identity of a people, what does that do to the psychology of the people?

SS: Bad things. Like any trauma, everyone at some point experiences a trauma. To be separated from our parents is a trauma. The Nazi genocide was a trauma for a lot of Jews and the descendants of Jews. To define yourself after a trauma is something perverted. You have to keep alive the memory of trauma. Even in the private life, to make the trauma alive, to make it so vivid, it’s a kind of illness. I think like one of my professors that we have to forget the Shoah. All the Goys have to continue to remember. All the non-Jews. But the Jews have to start to forget more and more the Shoah. Even in the private life, don’t try to make the trauma live again and again; that’s an illness, a perversion. •

Images courtesy of David Poe and Yossi Gurvitz via Flickr (Creative Commons).