Long before Garrison Keillor debuted A Prairie Home Companion in 1974, there were prairie home companions on the radio every day.

Prairies are vast flat lands populated by shrubs, grasses, and wild herbs, with few trees and modest rainfall; the dry land cracks and is often dusty. Not very hospitable. North and South Dakota, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska are prairie states. California’s central valley and considerable portions of Colorado, Wyoming, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, and most of Minnesota are also thought of as prairieland. This part of America is also called, by some, The Heartland. Rarely, however, do the densely populated coasts of the country regard this vast mid-section of America as vital as that name might imply.

For many that migrated there in the 19th and early 20th century, it was their land of dreams. From 1836 to 1914, over 30 million Europeans immigrated to the United States. In the 19th century, people were encouraged to move out West. “Go West young man” was the clarion call put out by an Indiana newspaperman in 1851, and the slogan was picked up by Horace Greeley, New York Tribune editor and politician. Go West; many did. Among them were Germans, Slavs, Poles, Swedes, and Norwegians — immigrants who knew how to wrest life from hard soil. Like all immigrant groups, they carried their culture, their values, and their foodways with them.

The promise of a fecund earth proved to be true: crops, the same crops, sprung up year after year. Nature provided, at least for a time.

For a culture to survive, there must be a community to support it. Early on, and for a long time, great distances separated farmstead homes, small towns, and people with shared origins and values. Although the elements existed, a sense of community was often hard to achieve. Radio would change that forever.

Broadcasting

When Marconi’s turn-of-the-20th-century experiments with Hertzian waves became wireless telegraphy and that became radio transmission, the stage was set for a communication phenomenon. Once the fascination of crystal-set hobbyists gave way to the invention of radio, of “broadcasting” as we know it, the explosive growth of the new medium was unstoppable.

“The advent of every new technology of communication always brings with it the hope of ameliorating all the ills of society” (Wu 2010). Like TV and the Internet, radio started as an open system. Radio, like all media before or after, would be the tool to end all strife, bring education and prosperity to all. As with TV and the Internet, radio held that magical promise. As with its successors, TV and the Internet, radio would fall short of fulfilling the highest hopes of the naïve.

“There was no such thing as national radio, public or private. And for as long as such limitations persisted, so did the idealism surrounding radio” (Wu 2010). Early champions of the new medium saw radio as the ultimate tool for education and information. Radio owners could, they promised, just by listening, become fully educated. Instead, and in rather short order, the hoped-for “People’s University of the Air” would be charging tuition and the classroom would be more about entertainment than information and education.

Broadcasting, a term borrowed from seed dispersal, was first used by Dr. Frank Conrad, an enthusiastic HAM operator in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Working out of a barn that served as a research lab for Westinghouse, Conrad used the “wireless telephone,” as it was then known, for sending out music and sports scores. The concept of broadcasting, however, the reaching out to the many rather than the few, burst upon the scene with a single event.

It was November second, 1920, when Pittsburgh’s KDKA radio station sent out the results of the Harding-Cox Election, that broadcasting — sending a radio signal into the ether for any who could receive it — began. Westinghouse saw an opportunity and began regular broadcasts from a 100-watt transmitter in the hopes of selling their rudimentary radio sets, a small advance on the popular “cat-whisker” crystal sets then in use.

Four years later, there were 600 commercial radio stations in the nation. And by 1926 the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) had formed the first national radio network. Like so much in the new age of speed; the popularity of this novel object and concept was moving fast. In the Age of Speed, inevitably there would be speed bumps.

The 1920’s: It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.

An argument has been made that the opening lines to Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities are apt to this era: prosperity turned into despair. From its infancy, radio grew up in an environment of unprecedented growth and prosperity in America. Post-World War I giddiness had rapidly inflated a fragile financial and cultural balloon the scale of which would never again be repeated.

The “smart young things” met around a table at Manhattan’s, Algonquin hotel; George S. Kaufman, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, and Dorothy Parker. This talented, outspoken group of literary lions helped shape the culture of the day. The Harlem Renaissance was under way with W.E.B DuBois and Langston Hughes leading the charge, accompanied by raucous jazz at the integrated Cotton Club, opened in 1923 on West 142 Street. Radio would play its part in cultural transformation when, in 1927, the nascent Columbia Broadcasting System began broadcasting from the club.

By then, the “Lost Generation” had decamped for Paris; Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Henry Miller, artists, and artists manqué were making famous the salon that Pittsburgh ex-pat Gertrude Stein provided for them. Edna St. Vincent Millay was holding court in bohemian Greenwich Village, e.e. cummings was abandoning upper cases, Faulkner was making a case for a Southern Renaissance, and Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were cracking cases with the anti-hero detective. Clarence Darrow and Williams Jennings Bryan famously debated evolution, Prohibition made alcohol illegal, and Al Capone took over Chicago. Women got the vote, the flapper embodied the thoroughly modern, emergent feminist, and Lindbergh soloed the Atlantic. It was the best of times.

It was the era of promise and of fun. Fortunes were being made buying on margin at the stock exchange. Everyone and everything seemed tipsy. Joe College and Jazz Babies could get up to anything and Harry Houdini could get out of everything. “Every morning, every evening; Ain’t we got fun?” was the tuneful mantra of the day. Some saw the ominous under the frivolous in those lyrics, “… not much money, Oh but, honey, Ain’t we got fun?” It had to end.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us…

Everything changed abruptly — in one day. Beginning on October 24, 1929, Black Thursday, the stock market began a dramatic descent that lasted a month and would plunge the nation and the world into a decade that became known as the Great Depression. And, as if nature had conspired with greed, drought and the first of the dust storms, “black blizzards” they were called, began in the flat, dry prairie lands of the midwest the following year. Farmers had bankrupted the earth, rapaciously pursuing crop monoculture. For over six years, the winds blew the damaged, eroding earth, displacing millions of farming families and deepening the impact of the Great Depression.

“Though people experienced the Depression in a wide range of extremes, nearly all American women of every race and class shared a common experience: feeding their families on less money” (Schenone 2003).

It is in this extreme national circumstance that radio enjoyed its Golden Age.

In the previous year of great prosperity, 1928, a self-congratulatory Republican convention nominated the pro-business Commerce Secretary, Herbert Hoover, for President. He won handily. What a difference a year would make. The market crash was sudden and devastating. Even though he eventually abandoned his hands-off approach to the economy, it was far too late. Hoover had been early radio hobbyist, but failed to use the medium to help retain his presidency, and he was crushed under the weight of a nation in deepening financial desperation.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt defeated Hoover in the next election and became a master of the new medium. As president, his radio broadcasts, known as “fireside chats,” would attempt to mollify fears and solidify confidence that better days were ahead. The effective, intimate use of radio by Roosevelt was as groundbreaking in his day as the use of Twitter has been to contemporary politicians.

During the Great Depression, Radio’s Golden Age, the radio kept people connected. “Americans found radio could help them personalize their encroaching mass society in order to find ways to count within it and to gain a measure of control in their own lives” (Lenthall, 2007). Radio did that in a variety of ways.

Radio kept people informed. Radio, moreover, kept people entertained. Misery loved company, music — and a few laughs. Many musical and comedic personalities and commentators, both serious and not so, were forged on the radio during the 1930’s. Early radio delighted the downtrodden as well as the well-off with shows like Fibber Magee and Molly; Duffy’s Tavern, with vaudevillians Eddie Cantor, Jack Benny, Bob Hope, Red Skelton, and Jimmy Durante; and most of all with the enormously popular black-face comedy — Amos ‘n’ Andy. “No matter how the show came eventually to divide Americans, nobody disagrees that Amos ‘n Andy was radio’s first big hit. But it was far more than that; it was a show that, because it transfixed the nation, also transformed and transcended the medium itself, and first altered skeptical advertiser’s [sic] to radio’s vast appeal and drawing power” (Nachtman, 1998). Significantly, radio’s biggest and longest-running comedy hit was about “Two luckless but lovable black guys” — ordinary folks living ordinary lives, albeit African-American ordinary lives, during a time when misfortune knew no boundaries.

In many ways, radio saved the nation.

“Radio ownership more than doubled in the 1930’s, from about 40 percent of families at the decade’s start to nearly 90 percent ten years later. By 1940 more families had a radio than had cars, telephones, electricity or plumbing” (Lenthall, 2007). To say that radio had become, in a relatively short time, fundamental to society and, by extension, highly influential, would be an understatement. To a society, a mass culture, stricken by despair, beaten and abandoned by a dream, radio was there to uplift, to provide empathy, understanding, solace, advice, information, and, most importantly, that delightful distraction called entertainment. And in the process of providing so much to so many, radio broadcasters, nationally syndicated and local, were changing the community and the culture. “The decade of the Great Depression saw the debut of radio programs that would form the attitude of an evolving mass audience towards mass media culture in the twentieth century” (Lenthall, 2007). Welcome the Radio Homemaker.

The Advent of the Radio Homemaker

Just five years after the ground-breaking multiple-station presentation of the July 2, 1921 Dempsey-Carpentier heavyweight championship bout carried by KDKA (Pittsburgh), Aunt Sammy went on the air.

The idea — a friendly auntie version of Uncle Sam — was born out of the need to distribute market reports from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Even in radio’s earliest crystal-set days, it sent out crop price reports vital to midwestern farmers. The Office of Information, headed by Milton Eisenhower, was created in 1926 to disseminate its information over the new medium of radio. Dull but fact-filled, the United States Radio Farm School was one of its early manifestations. Another ten-minute specialty broadcast, “imaginative — if not unintentionally hilarious — [was], The Autobiographies of Infamous Bugs and Rodents.” Three radio writers in the division developed these and other programs, planned to bring scientific agriculture to the farmer who owned a radio (Grief, 1975 intro.). But what about the farmer’s wife?

In spite of early century advances to elevate the importance of housekeeping and cooking to Domestic Science, the average woman in 1926 led a dreary, housebound, chore-laden existence. Clothing was still mostly homemade, the wash was boiled, the iron had to be heated on a fire, and food was prepared from scratch. Leisure was not a concept; contact with the outside world was rare and brief. By its nature, life was inherently lonely.

In October 1926, on 50 stations across the United States, an announcer welcomed listeners to the first Housekeeper’s Chat: “This morning we are going to introduce Aunt Sammy, the best authority we know on housekeeping … Ask your neighbors over to meet her. Send your problems to her. Make her your friend and advisor” (Grief, 1975). Imagine finding a kind ear with whom you could commiserate. Aunt Sammy was officially known as the “radio representative of the U.S. Bureau of Home Economics.” The scene was set for an intimate two-way exchange that personified the medium and was to be duplicated and repeated for decades by the Radio Homemaker.

First conceived as a two-way transmission (it survives as HAM or amateur radio), the two-way aspect of radio never really went away. Dedicated listeners wrote letters to their favorite broadcaster, to station owners, and to product sponsors, further embedding their personal relationship with the medium and it practitioners. “Listeners crafted new kinds of relationships with the people and fictional characters they heard. They used radio to reinvent public relationships as personal relationships. They successfully imagined that the new mass communication of radio resembled older, more obviously intimate forms. And they befriended the voice they heard through the medium” (Lenthall 2007). This phenomenon occurred early, was strong, and still exists.

The fictional Aunt Sammy was the “mistress of kitchen and pantry, of garden and nursery; wise to the ways of old-fashioned housekeeping, but affecting a flapper’s boyish bob.” This being radio, the boyish bob no doubt manifested more in attitude than reality. “Entertaining and natural and friendly – plus informative – these were the traits given to Aunt Sammy by her creators … But to these Aunt Sammy added a new dimension: a simmering desire for freedom from pots and pans” (Grief, 1975).

Very popular in rural markets, the focus of the program was menus and recipes, but Aunt Sammy had plenty to say about clothing, furniture, newfangled appliances and how to use them; she commented on world affairs, the latest fads, and even told jokes. In 1927, radio homemaker Aunt Sammy responded to thousands of requests with the first printed collection of her radio recipes. The first print run of 50,000 sold out in a month and became the first cookbook printed in braille.

Josephine Hemphill, a graduate of Kansas State Agricultural College (now Kansas State University), was responsible for Aunt Sammy’s alluring banter. Ruth Van Deman, a specialist in home economics, prepared the menus and recipes, and was one of the on-air Aunt Sammies. “This is no caviar and truffle service for jazz-jaded appetites,” she said, “we aim to make the menus simple, well-balanced, delicious, and adaptable to the food supplies in all parts of the country” — food supplies that soon began to come up short.

As many as 50 “Aunts,” utilizing regional accents and speech patterns, read from prepared scripts of household hints, recipes, and humorous banter at regional radio stations. The answers to questions asked, recipes, household hints, and advice, from defining what a vitamin was to how to put up corn relish, cook wieners the “modern way,” or plan the daily menu — all originated from one place. A measure of homogeneity was inevitable, even desirable. What was the point of mass communication if not to unify the “global village”?

The Depression took most of the wind out of Aunt Sammy’s breezy sails. “In an era when Americans were spellbound by radio, women turned to it faithfully. They put down their housework and fetched a pen to write down recipes” (Schenone 2003). Suddenly Aunt Sammy was teaching the desperate how to survive on grain and milk, the merely poor how to make every scrap count, to make clothes from seed sacks. “The cooking networks set up by the domestic scientists and reinforced during World War I continued to be important. Radio homemakers, culinary writers, women’s columnists, and food manufacturers all offered American women ideas for dishes that used fillers like bread crumbs, crackers, and cereals” (Schenone 2003). Aunt Sammy, however, was not made for the Depression.

By 1932, 194 stations were broadcasting Housekeeper’s Chat. The (NBC) Blue network’s Farm and Home Hour began to chip away at Aunt Sammy’s rural American audience. By 1933, the “family” she had created began to disappear, and in 1934 Aunt Sammy was all but gone, survived by an announcer reading dull letters from correspondents of the Department of Agriculture.

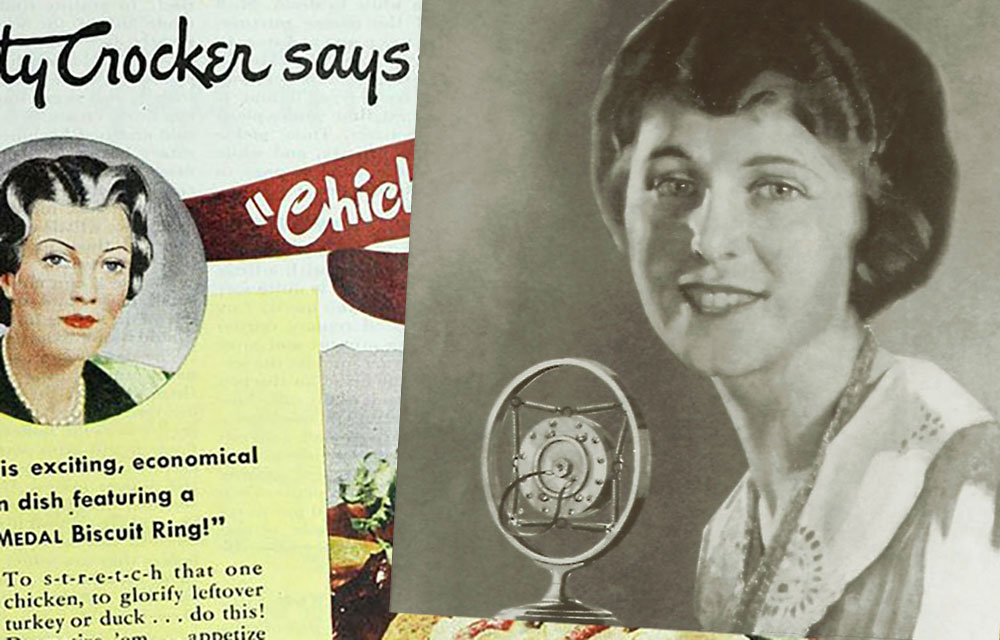

Betty Crocker

The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air was already well-established when times turned bad. Promotional cookery books featuring a manufacturer’s products were already commonplace when the Washburn-Crosby Company, maker of Gold Medal flour, leveraged their fictional homemaker, Betty Crocker, with a Friday morning radio show that debuted in 1924. The show would eventually become a network program with a national audience. University of Minnesota-educated home economist Marjorie Child Husted created Betty Crocker. For two decades, Husted wrote the scripts and provided the radio voice for Betty. The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air became one of the longest-running shows in radio history.

Betty’s “kitchen-tested recipes” for Gold Medal flour were extremely popular. Radio devotees sent away for a little dove-tailed wooden box filled with the recipes. As with Aunt Sammy, promotional cookery books supported the broadcasts after Washburn-Crosby had become the conglomerate known as General Mills. 21 home economists were eventually hired to meet the listener demand for recipe booklets and information. In 1933, to promote their new quick biscuit product, Bisquick®, they went the fashionable route, Betty Crocker’s 101 Delicious Bisquick Creations, As Made and Served by Well-Known Gracious Hostesses, Famous Chefs, Distinguished Epicures and Smart Luminaries of Movieland.

Ida Bailey Allen

Born in 1885, Ida Bailey Allen was a real life radio homemaker. She hosted The National Radio Homemaker’s Club on the Columbia Network from 1928-1935. With a magazine, syndicated newspaper columns, books, and a radio cooking show endorsing Pillsbury Flour, Sunshine Biscuits, and Coca Cola, today we would call her a brand. A former editor of Good Housekeeping, President and founder of the National Radio Home-Makers Club, Bailey Allen was also an author of more than 50 cookbooks including: 104 Prize Radio Recipes with 24 Radio Home-maker’s Talks; Mrs. Allen on Cooking, Menus, and Service, later called Ida Bailey Allen’s Modern Cookbook: 2500 Delicious Recipes; and the Everyday Cookbook. One in three American households were said to own a copy of at least one of her books.

In 104 Prize Radio Recipes, she exhorts her radio sisters:

There are twenty million of us Home-Makers. That is our job. Sometimes we become so enmeshed in it that we cannot look beyond the narrow confines of our own home. … To be a successful Home-Maker one must keep up. Any woman who has the wish can do it. Magic is not confined to myths or the Dark Ages. There is Magic today. The Magic of great manufacturers who have taken drudgery away — the Magic of gas and electricity — the Magic of books and libraries — and we have the Radio — that makes the Whole World Kin.

Spoken like a true believer in radio and commerce. “Radio makes the whole world kin.”

The stock market crash and the long Depression that ensued put an end to the emerging new, more independent woman and pushed her right back into the kitchen. According to a 1936 Gallup poll, 82 percent believed that women were just where they belonged — in the home. The thoroughly modern woman may have, along with everyone else, been diminished by circumstance but remained heroic in her efforts to provide for her family and, in many cases, to survive.

Radio homemakers adapted. In her Depression-era cookbooks, Ida Bailey Allen’s Money Saving Cook Book: How to buy economically, how to cook economically and how to avoid waste and Ida Bailey Allen’s Everyday Cook Book: Tested Recipes, Balanced Menus, Money-Saving Hints, Setting the Table and Serving, she answered questions her readers posed and offered advice that reflected the needs and anxiety of the times.

All Radio is Local: KMA Radio Homemakers

In many ways, radio homemakers were the forerunners of contemporary talk radio and internet bloggers; sharing experiences, opinions, and information. They are, however, separated by more than time. Radio homemakers “visited” on the radio as they would over the fence or the clothesline, in line at the grocery store or at the post office. The distance between midwesterners and prairie farm wives was often far greater than a clothesline, and the trip to the post office a considerable journey. The radio supplied the proximity, the intimacy, and they came to depend on it.

This dependence had everything to do with what Marshall McLuhan describes as radio reviving the “ancient experience of kinship webs of deep tribal involvement. … Telegraph and radio evoked archaic tribal ghosts of the most vigorous brand” (McLuhan 1964). For many listeners, the “visits” of radio homemakers, women like themselves and sometimes men, were where they found companionship, solace, useful advice — kinship webs to be sure.

If it is true that all politics are local, then all radio, nationally syndicated or otherwise, is also local. “By its very nature, early American radio was local, and hence the roots of ‘localism’ in broadcasting” (Wu, 2010). It is an undeniable aspect of radio that it is always perceived as local even when listeners know otherwise.

Truly local, and specifically midwestern, was KMA radio in Shenandoah, Iowa.

Station KFNS was already a success in Shenandoah when Earl May went on the air with KMA radio. May’s rival in the seed business, Henry Field, had begun broadcasting under the call letters of KFNS from Seed House no.1 in February of 1924. The “Friendly Farmer” station was broadcasting on the air, and the response was immediate and “overwhelmingly favorable” (Kirby, R, 1985). Earl May took his lead from Henry and made it his goal to do what Henry did — only bigger and better.

The young, enterprising Earl May, wanting to build the May Seed & Nursery business, saw the new technology of radio, as had Henry Field, as the way to do it. As Henry did before him, he bused talented singers, musicians, and speakers some 60 miles to Omaha, Nebraska, to station WOAW, for a variety show of musical talent and agricultural information — and to promote his seed business. What firmly convinced Earl of the efficacy of the radio as a commercial medium was when he offered free iris bulbs to the first 10,000 listeners who would send a card to the station. He responded to every one and included a catalogue of May Company products.

In June of 1924, a modest broadcasting studio was built at May Seed company’s administration building, connected by telephone lines to WOAW, the longest remote “network” connection of their day. The following year, Earl secured a license from the FCC to broadcast under the call letters of KMA radio and Earl May put himself at the broadcast desk.

The radio station became a family effort with Earl’s supportive wife, Gertrude, singing as well as talking on the radio. It was Mamie Miller, however, who began the long line of remarkable women broadcasters that “neighbored” on the air over KMA radio.

“Our little town of 5,000 had two big radio stations that spread all over the country when it first started. They cranked up their power and the signal reached the Pacific coast,” said Evelyn Birkby. Earl was nothing if not a promoter and as KMA grew, so did his seed business.

In February of 1927, Henry Field began construction on a new broadcast auditorium. In the month of May (of course) of the same year, Earl began to build his own 1,000-seat auditorium topped with a Moorish minaret. Folks came to see the radio broadcasts, as do contemporary audiences of NPR’s Prairie Home Companion. A glass curtain separated the audience from the broadcasters and the airwaves. Mayfair, as it was known, was also a popular venue for movies and a variety of regular staged presentations. A startling increase in seed sales of 425 percent over the previous year had helped finance the project (Kirby, R, 1985).

KMA broadcasts included early morning farm reports, live musical groups — both local and touring — inspirational programs, syndicated shows, KMA’s own performing troupe called “The Country School,” and, of course, the radio homemakers for which they became known.

In keeping with the new respectability that homemaking enjoyed, some shows were called Domestic Science Talks, while others were a little more cozy with names like The Home Hour or simply a Visit With ____. The earliest homemakers included Leona Teget, Bernice Currier, June Case, and others. During the Depression, radio homemaker personalities became strongly identified with KMA and built a close, intimate following. “Some of KMA’s women broadcasters had been trained as home economists, and they structured their programs around teaching the techniques of homemaking. Other relied for inspiration on experience rather than coursework,” said Kirkby (2011).

In 1926, Helen Field Fischer (one of Henry’s five daughters) advised Leanna Driftmier on her radio debut: “don’t be nervous about it. … Just talk as though you were sitting in your own living room talking with friends who have just dropped in” (Kirby, R, 1985). Leanna took that advice. After sitting in on KFNS’s Mother’s Hour, she was eventually asked to take over the program. When she complained that she “couldn’t possibly think of enough to say,” Helen Field reminded her that anyone with seven children ought to have plenty to talk about. Her show, called Kitchen Klatter (first on KFNS, then on KMA, and eventually syndicated), became the longest-running homemaker program in the history of radio (Kirkby, E. 1991). The Kitchen Klatter magazine inevitably followed.

The list of KMA radio homemakers is long and the lives of the on-air women are compelling. What made them credible and valuable was their knowledge, as well as their ability to form relationships over the air waves. “They have been willing to share their personal lives with listeners in much the same way close neighbors confide in one another. The audience has come to trust these radio personalities as friends,” wrote Evelyn Birkby, one of that notable sorority, in Neighboring on the Air.

“During the Depression farm life and farm women were neglected … just not seen as important,” said Evelyn. “Women at the time were not thought of as on equal footing with men. They needed something to encourage them. Many of the women saved the farms with pin money from selling cream and eggs but they weren’t thought of as important because they were not sitting on a tractor.”

The success of the radio homemakers, these prairie home companions, was widespread and steady. “They talked about day-to-day events in their families with such regularity and familiarity that a listenership followed the real-life developments with a loyalty much like the fervor of fans of today’s soap operas” (Birkby, R. 1985). Describing radio “visits,” a listener wrote to Evelyn, “It was like listening to One Man’s Family [radio’s longest running serial, 1932-1959], watching the life of a family unfold.”

In the case of KMA homemakers, the life unfolding was real. Many would broadcast from their homes, from their kitchens, preparing food on- and off-microphone with all of the true-to-life sound effects. Daughters and sometimes sons took part, now and again the family dog or, in one instance, a rooster was heard. “Tales of their own daily experience, of thoughtful observances and always the recipes, where all part of the radio homemakers appeal” (Birkby, R, 1985).

Many of the homemakers had struggles of their own. “They were stoic, they accepted their circumstances,” Evelyn recalled. After an automobile accident in 1930, Leanna Driftmeir, although confined to a wheelchair, continued her broadcasts until 1976, when she was past 90 years old.

A caring Earl May hired Jessie Young when she and her husband found themselves suddenly out of work. By 1926, her Stitch and Chat Club was on the air. Jessie was the first radio homemaker to broadcast directly from her home. This eventually became A Visit with Jessie Young. Jessie had grown up poor in nearby Essex, and as the Depression deepened, she empathized and was helpful to her listeners based on hard-learned experience.

Bernice Currier joined KMA in 1927. A University of Nebraska music major, Bernice first performed on the air as a violinist. She appeared on The Home Hour and The Domestic Science Show, narrated fashion shows on the radio, organized cooking contests, and voiced commercials. She taught music in the public schools and gave private lessons in an effort to bring up her four children after her marriage dissolved. Bernice developed a simple A-B-C step method of recipe writing that listeners enjoyed. Life was busy and difficult and she shared that with her listeners. “Radio homemakers had a positive view of life in spite of their trials, radio homemakers made them happy. They’d talk of children, of bringing up children — they talked about everything. In those days there were no support groups, no Dear Abby, no grief counselors. The homemakers had a close relationship with their listeners,” recalled Evelyn.

Radio homemakers showed their listeners how to navigate difficult times with ways to save, to grow their own food, to use leftovers, to dry foods and smoke meat, and to can fruit, vegetables, and meats. They offered recipes that were easy to make and taught them to sew clothes from seed sack cloth. “I did it myself,” said Evelyn. “Mother bought cloth feed sacks that had patterns on them, get four pounds of matching whatever, and when they were emptied make tablecloths, curtains, and so forth and lots of underpants!”

“When you say the word Depression … you realize it was a depressed era, people were very discouraged. A listener wrote in to tell me that her Mother wrote down very carefully every recipe she heard on the radio. Never cooked a one. It was the connection that counted. Food does so much more than feed the body.” Superficially, recipes brought prairie women together. On a deeper, more significant level, the recipes would lead to food sharing, to caring, and in food was found the symbolic significance of a promise for a better day.

Radio homemakers are, today, largely forgotten. There are no surviving scripts or transcripts because there were none. Few taped recordings of shows of the KMA homemakers exist because few thought to do so and those few that existed have disappeared, according to Evelyn. “During the depression and afterwards radio homemakers and the audiences they served, were not taken seriously especially by the people on either coast.”

There were over a decade of hundreds of broadcasts. Each radio homemaker made an impression and reinforced an overarching ideal of the good neighbor: always there when you need them with a willing ear, a kind word, and a plate of freshly baked cookies.

The “we’re all in this together” mentality, the up-by-the-bootstraps, grace under pressure, “can-do” attitude that came to characterize the American ethos came from this decade of the Golden Age of Radio and its forgotten radio homemakers. As the decade drifted from one of depravation and despair to war and destruction, there were, at the end, over 20 years on the clock that tested the resolve of the majority of Americans. When the community and culture emerged from the worst of times, Radio Homemakers had had a profound impact on American cooking and on the formation of the definition of the American Family and American Family Values in the 20th century — even if just in the imagination and aspirations of the many.

No culture without a community; no community without communication. The message was communicated, and the medium over which it was communicated during the Great Depression and the Golden Age of Radio had a stunning and long-lasting effect. Communication changed the community, and the community changed the culture. •

Lead image uses a promotional photo of Betty Crocker courtesy of the General Mills Archives