We enter Panem, home of The Hunger Games, a dystopian film and book franchise that centers on the oppression of the 12 mostly impoverished Districts controlled by the Capital. Every year, the Capital holds an event called The Reaping where they make each one of the Districts sacrifice two children to The Hunger Games. During the event, they are forced to kill one another until there is only one left standing. That last child is the “victor” and wins a year’s worth of food for their district. We enter during the 74th Hunger Games, where the focus is on a young, white teenage girl named Katniss. All but two of the 24 tributes are white.

Mainstream dystopian fiction focuses primarily on the white protagonist and white-dominated societies — The Hunger Games is no exception. This trend can be seen in both Divergent (which has a white, female lead) and The Maze Runner (which has a white, male lead). Dystopian literature is defined as a sub-genre most commonly used within speculative fiction and science fiction. It shows a fictional world that explores social and political structures of a world in peril. To live in a dystopia is to be a part of a world that is impoverished, living in squalor, and/or highly oppressed. Dystopian fiction is that which dramatizes what it is like to be a marginalized within a culture, a body, and a world. Which is why it is so shocking that, at the margins, every character is white.

In a theater filled with people, we are all fixated on a young, white protagonist who is ready to lead revolutions against oppressors. We hold our breath, waiting to see if her elaborate plans pan out. We cheer when she destroys labs, dams, buildings, and transportation. We applaud as she kills those who work for her oppressors and even sometimes the oppressors themselves. We cry when one of her friends dies during the rebellion.

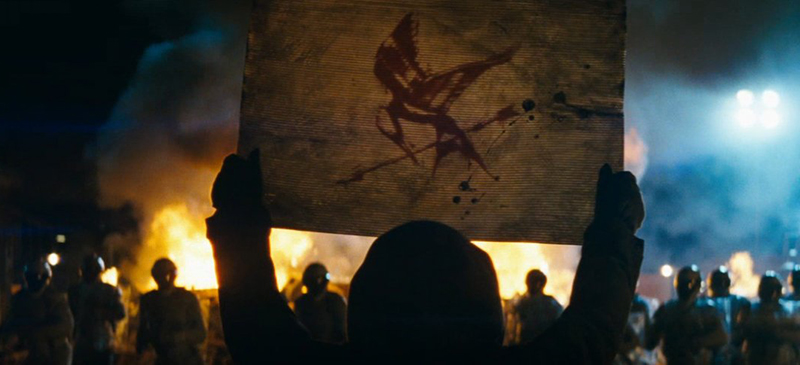

During the Hunger Games, a young black girl is killed at the hands of another child. Her district mourns her death. A revolution is born within Katniss as she holds her dead body. She vows to burn down everything the Capital stands for. In order to stop her, District 12 burns to the ground at the hands of the Capital. A revolt begins and citizens of each District begin to destroy everything within their borders. In the end, a new nation is born. Everyone in the theater applauds.

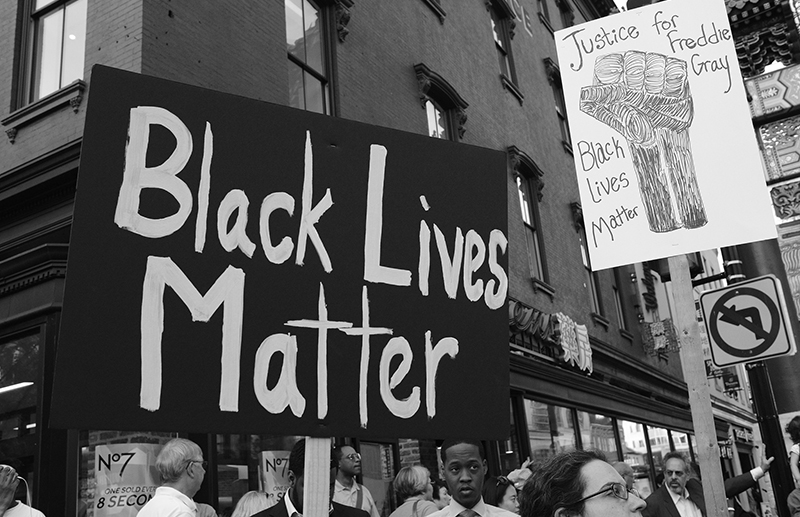

The narrative of The Hunger Games can be compared in many ways to the city of Baltimore after Michael Brown’s shooting: They are both tales of dystopian fiction, but only one of them is seen as heroic. We are only allowed to see revolution as a positive thing when it is dressed up as an “attractive” young, white actor or actress. The irony is that there are people who live this reality who are not afforded the right to fight back and create a new nation. Who are not pretty enough to justify the carnage that they create. Who refuse to swallow the saying “all lives matter” because we know it is an act of discrimination against others. I have never once heard someone say, “Why can’t both the Districts’ and the Capital’s lives matter?”

We enter Ferguson, a land of people who are forced to sacrifice everything to keep their children safe. A young black boy is killed and left in the street to rot in the sun. His mother and city mourn his death. A revolution kicks up as a mother cries for her baby. A plan is made, a revolt is born, and the city begins to burn. Rioting begins, and those within the city begin to destroy everything that is within their own borders. In the end, a riot squad is called. Police in full body armor turn on those they are supposed to protect.

I have also sat in front of the television and watched a city of people ready to lead a revolution against their oppressors. I have held my breath, waiting to see if their elaborate plan pans out. They were reprimanded for destroying cars, windows, and buildings. Society turned its head when one of the rebels was killed during the rebellion. Nothing changed. Everyone who watched the fallout in the news was silent or condemned those who fought back. No one applauded.

We understand that what happens to the children in the Capital is wrong. They have the privilege of being seen as children and therefore innocent. We understand that the Capital is wrong to ask district families year after year to send their children to be slaughtered. Their whiteness allows them a humanity that black children — even in the film — are not given. Fans of the film left angry that Rue was a little black girl in the movie even though she was a little black girl in the books — they wanted protagonists that looked like them and a film that didn’t remind them of real-life issues. Because of her race, her death was less upsetting than that of Primrose, Katniss’ sister, who’s dead body we never see. Meanwhile, we watch Rue bleed to death the same way we watched Michael Brown, Philando Castille, Trayvon Martin, and countless other young, black men die. Yet they are not worth a hashtag, a song carried through the air by mocking jays, a city of busted windows, a revolution, or a new world that doesn’t ask them to sacrifice themselves.

Those who ask for justice from their real-life dystopia are condemned and belittled. They are told to wait, to protest, but only non-violently, to act and dress in ways worthy of respect so they won’t be targets. There is a history of being asked to wait while police officers beat unarmed black citizens. Of people being called thugs while they are hosed down, while dogs bite them. There is no right way to ask for your rights when those in power don’t want to give them to you. This is why we protest.

This is why Katniss fought back. Why a theater full of people applauded while she destroyed buildings and killed Capital police officers. It seems the only way to tell the story of real people who fight for their rights is to show it through a white lens. It has to be palatable to be worth creating. Even if what you are saying is true, it doesn’t matter if it makes others uncomfortable. But there is no change if people don’t confront what makes them uncomfortable. Pretending that race only exists when you are talking about slavery or the civil rights movement invalidates other experiences.

Those who do write speculative and dystopian fiction with black main characters are pushed to the side. Octavia Butler combines science fiction and slavery in the novel Kindred, showing how traumatic it was to be a slave while at the same time showing how easy it can be to become acclimated to abuse. Octavia Butler occupied the cross-section of science fiction and race writing; however, her writing and writing by others like her is nowhere near as well-known as The Hunger Games. Hollywood is not interested in putting money into those stories.

There is a privilege in having your story told while the world watches and cheers you on. However, the story of Katniss is not just happening in a theater, but in real life, and those real stories of loss and struggle are being silenced.

There is nothing more abusive than being silenced and told that your story is only worth anything if it fits into a box. Black stories only matter when they are talking about the past or personify stereotypes, and women’s stories only matter if we are getting married or falling in love. Minorities’ stories all exist to reassure white people that they are right about us. When we step outside of that box, we become a threat — thugs, dangerous — code words that all mean the same thing.

Dystopian fiction is not the only place we need more representation. Black stories are not only about suffering. Blackness is a story of oppression, but it is also a story of creation. I want a movie about the first successful open heart surgery done by Dr. Daniel Hale Williams. I want a movie about the Black Panthers and all they did to protect their community. Blackness is a story of resilience and rebellion and serving everything that should have killed you. But I also want the story of our suffering to be ours. I want a black girl at the head of a rebellion. I want to sit in an audience and cheer when she takes down the Capital. I want everyone to weep for those she has lost. Even for just two hours, I want Black bodies to be worthy of applause. •

Images courtesy of screenshots by author and Arash Azizzada, Stephen D. Melkisethian and scottlum via Flickr (Creative Commons)